Crash of a Boeing 777-31H in Dubai

Date & Time:

Aug 3, 2016 at 1238 LT

Registration:

A6-EMW

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Thiruvananthapuram - Dubai

MSN:

32700/434

YOM:

2003

Flight number:

EK521

Crew on board:

18

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

282

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

5123.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

1292

Aircraft flight hours:

58169

Aircraft flight cycles:

13620

Circumstances:

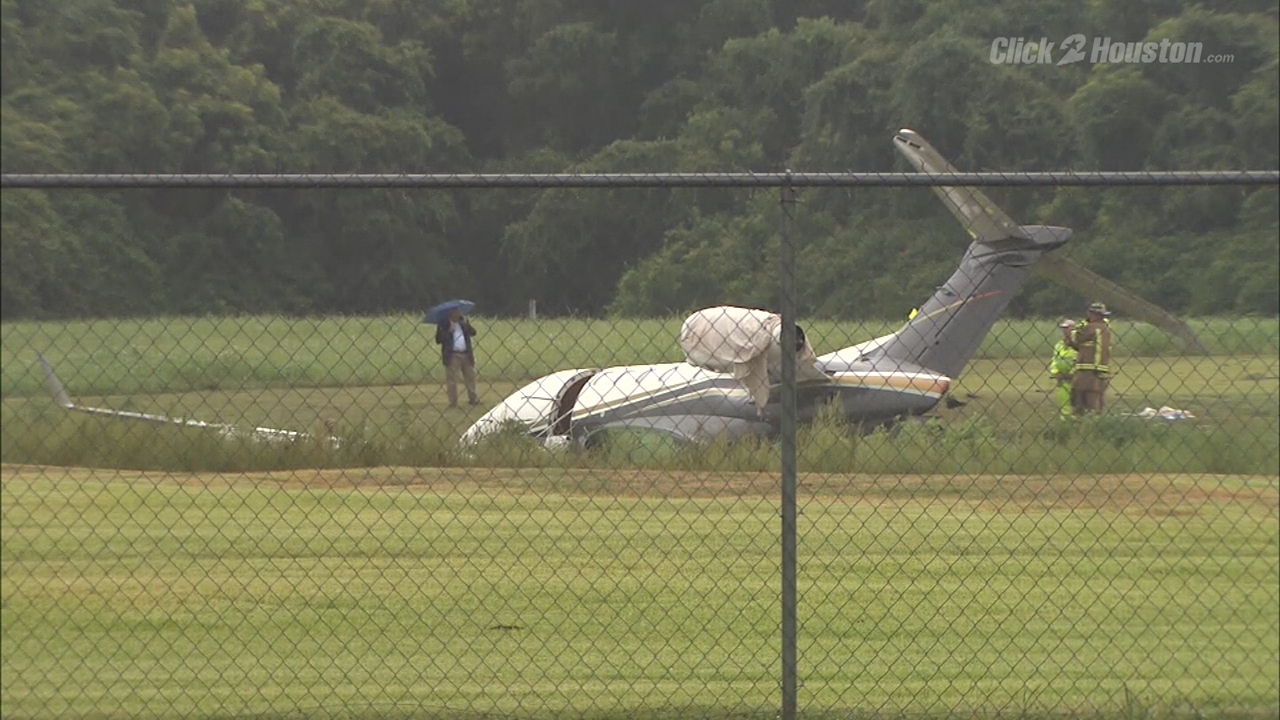

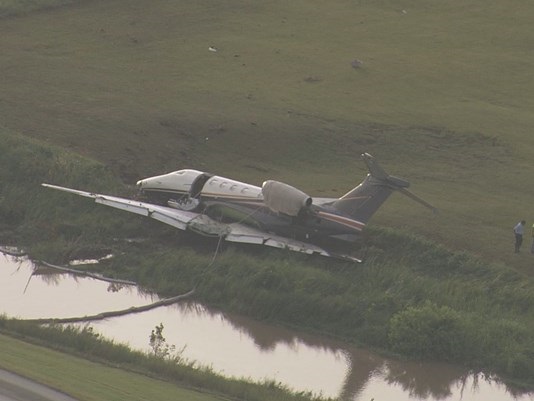

On 3 August 2016, an Emirates Boeing 777-31H Aircraft, registration A6-EMW, operating a scheduled passenger flight UAE521, departed Trivandrum International Airport (VOTV), India, at 0506 UTC for a 3 hour 30 minute flight to Dubai International Airport (OMDB), the United Arab Emirates, with 282 passengers, 2 flight crew and 16 cabin crew members on board. The Commander attempted to perform a tailwind manual landing during an automatic terminal information service (ATIS) forecasted moderate windshear warning affecting all runways at OMDB. The tailwind was within the operational limitations of the Aircraft. During the landing on runway 12L at OMDB the Commander, who was the pilot flying, decided to fly a go-around, as he was unable to land the Aircraft within the runway touchdown zone. The go-around decision was based on the perception that the Aircraft would not land due to thermals and not due to a windshear encounter. For this reason, the Commander elected to fly a normal go-around and not the windshear escape maneuver. The flight crew initiated the flight crew operations manual (FCOM) Go-around and Missed Approach Procedure and the Commander pushed the TO/GA switch. As designed, because the Aircraft had touched down, the TO/GA switches became inhibited and had no effect on the autothrottle (A/T). The flight crew stated that they were not aware of the touchdown that lasted for six seconds. After becoming airborne during the go-around attempt, the Aircraft climbed to a height of 85 ft radio altitude above the runway surface. The flight crew did not observe that both thrust levers had remained at the idle position and that the engine thrust remained at idle. The Aircraft quickly sank towards the runway as the airspeed was insufficient to support the climb. As the Aircraft lost height and speed, the Commander initiated the windshear escape maneuver procedure and rapidly advanced both thrust levers. This action was too late to avoid the impact with runway 12L. Eighteen seconds after the initiation of the go-around the Aircraft impacted the runway at 0837:38 UTC and slid on its lower fuselage along the runway surface for approximately 32 seconds covering a distance of approximately 800 meters before coming to rest adjacent to taxiway Mike 13. The Aircraft remained intact during its movement along the runway protecting the occupants however, several fuselage mounted components and the No.2 engine/pylon assembly separated from the Aircraft. During the evacuation, several passenger door escape slides became unusable. Many passengers evacuated the Aircraft taking their carry-on baggage with them. Except for the Commander and the senior cabin crew member who evacuated after the center wing tank explosion, all of the other occupants evacuated via the operational escape slides in approximately 6 minutes and 40 seconds. Twenty-one passengers, one flight crewmember, and six cabin crew members sustained minor injuries. Four cabin crew members sustained serious injuries. Approximately 9 minutes and 40 seconds after the Aircraft came to rest, the center wing tank exploded which caused a large section of the right wing upper skin to be liberated. As the panel fell to the ground, it struck and fatally injured a firefighter. The Aircraft was eventually destroyed due to the subsequent fire. Following the Accident, the Operator (Emirates), the General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA), Dubai Airports and Dubai Air Navigation Services (‘dans’) implemented several safety actions. In this Final Report, the AAIS issues safety recommendations addressed to the Operator, the GCAA, The Boeing Company, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Dubai Airports, ‘dans’, and the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

Probable cause:

The Air Accident Investigation Sector determines that the causes of the Accident are:

(a) During the attempted go-around, except for the last three seconds prior to impact, both engine thrust levers, and therefore engine thrust, remained at idle. Consequently, the Aircraft’s energy state was insufficient to sustain flight.

(b) The flight crew did not effectively scan and monitor the primary flight instrumentation parameters during the landing and the attempted go-around.

(c) The flight crew were unaware that the autothrottle (A/T) had not responded to move the engine thrust levers to the TO/GA position after the Commander pushed the TO/GA switch at the initiation of the FCOM Go-around and Missed Approach Procedure.

(d) The flight crew did not take corrective action to increase engine thrust because they omitted the engine thrust verification steps of the FCOM Go-around and Missed Approach Procedure.

The Investigation determines that the following were contributory factors to the Accident:

(a) The flight crew were unable to land the Aircraft within the touchdown zone during the attempted tailwind landing because of an early flare initiation, and increased airspeed due to a shift in wind direction, which took place approximately 650 m beyond the runway threshold.

(b) When the Commander decided to fly a go-around, his perception was that the Aircraft was still airborne. In pushing the TO/GA switch, he expected that the autothrottle (A/T) would respond and automatically manage the engine thrust during the go-around.

(c) Based on the flight crew’s inaccurate situation awareness of the Aircraft state, and situational stress related to the increased workload involved in flying the go-around maneuver, they were unaware that the Aircraft’s main gear had touched down which caused the TO/GA switches to become inhibited. Additionally, the flight crew were unaware that the A/T mode had remained at ‘IDLE’ after the TO/GA switch was pushed.

(d) The flight crew reliance on automation and lack of training in flying go-arounds from close to the runway surface and with the TO/GA switches inhibited, significantly affected the flight crew performance in a critical flight situation which was different to that experienced by them during their simulated training flights.

(e) The flight crew did not monitor the flight mode annunciations (FMA) changes after the TO/GA switch was pushed because:

1. According to the Operator’s procedure, as per FCOM Flight Mode Annunciations (FMA), FMA changes are not required to be announced for landing when the aircraft is below 200 ft;

2. Callouts of FMA changes were not included in the Operator’s FCOM Go-Around and Missed Approach Procedures.

3. Callouts of FMA changes were not included in the Operator’s FCTM Go-Around and Missed Approach training.

(f) The Operator’s OM-A policy required the use of the A/T for engine thrust management for all phases of flight. This policy did not consider pilot actions that would be necessary during a go-around initiated while the A/T was armed and active and the TO/GA switches were inhibited.

(g) The FCOM Go-Around and Missed Approach Procedure did not contain steps for verbal verification callouts of engine thrust state.

(h) The Aircraft systems, as designed, did not alert the flight crew that the TO/GA switches were inhibited at the time when the Commander pushed the TO/GA switch with the A/T armed and active.

(i) The Aircraft systems, as designed, did not alert the flight crew to the inconsistency between the Aircraft configuration and the thrust setting necessary to perform a successful go-around.

(j) Air traffic control did not pass essential information about windshear reported by a preceding landing flight crew and that two flights performed go-arounds after passing over the runway threshold. The flight crew decision-making process, during the approach and landing, was deprived of this critical information.

(k) The modification of the go-around procedure by air traffic control four seconds after the Aircraft became airborne coincided with the landing gear selection to the ‘up’ position. This added to the flight crew workload as they attentively listened and the Copilot responded to the air traffic control instruction which required a change of missed approach altitude from 3,000 ft to 4,000 ft to be set. The flight crews’ concentration on their primary task of flying the Aircraft and monitoring was momentarily affected as both the FMA verification and the flight director status were missed.

(a) During the attempted go-around, except for the last three seconds prior to impact, both engine thrust levers, and therefore engine thrust, remained at idle. Consequently, the Aircraft’s energy state was insufficient to sustain flight.

(b) The flight crew did not effectively scan and monitor the primary flight instrumentation parameters during the landing and the attempted go-around.

(c) The flight crew were unaware that the autothrottle (A/T) had not responded to move the engine thrust levers to the TO/GA position after the Commander pushed the TO/GA switch at the initiation of the FCOM Go-around and Missed Approach Procedure.

(d) The flight crew did not take corrective action to increase engine thrust because they omitted the engine thrust verification steps of the FCOM Go-around and Missed Approach Procedure.

The Investigation determines that the following were contributory factors to the Accident:

(a) The flight crew were unable to land the Aircraft within the touchdown zone during the attempted tailwind landing because of an early flare initiation, and increased airspeed due to a shift in wind direction, which took place approximately 650 m beyond the runway threshold.

(b) When the Commander decided to fly a go-around, his perception was that the Aircraft was still airborne. In pushing the TO/GA switch, he expected that the autothrottle (A/T) would respond and automatically manage the engine thrust during the go-around.

(c) Based on the flight crew’s inaccurate situation awareness of the Aircraft state, and situational stress related to the increased workload involved in flying the go-around maneuver, they were unaware that the Aircraft’s main gear had touched down which caused the TO/GA switches to become inhibited. Additionally, the flight crew were unaware that the A/T mode had remained at ‘IDLE’ after the TO/GA switch was pushed.

(d) The flight crew reliance on automation and lack of training in flying go-arounds from close to the runway surface and with the TO/GA switches inhibited, significantly affected the flight crew performance in a critical flight situation which was different to that experienced by them during their simulated training flights.

(e) The flight crew did not monitor the flight mode annunciations (FMA) changes after the TO/GA switch was pushed because:

1. According to the Operator’s procedure, as per FCOM Flight Mode Annunciations (FMA), FMA changes are not required to be announced for landing when the aircraft is below 200 ft;

2. Callouts of FMA changes were not included in the Operator’s FCOM Go-Around and Missed Approach Procedures.

3. Callouts of FMA changes were not included in the Operator’s FCTM Go-Around and Missed Approach training.

(f) The Operator’s OM-A policy required the use of the A/T for engine thrust management for all phases of flight. This policy did not consider pilot actions that would be necessary during a go-around initiated while the A/T was armed and active and the TO/GA switches were inhibited.

(g) The FCOM Go-Around and Missed Approach Procedure did not contain steps for verbal verification callouts of engine thrust state.

(h) The Aircraft systems, as designed, did not alert the flight crew that the TO/GA switches were inhibited at the time when the Commander pushed the TO/GA switch with the A/T armed and active.

(i) The Aircraft systems, as designed, did not alert the flight crew to the inconsistency between the Aircraft configuration and the thrust setting necessary to perform a successful go-around.

(j) Air traffic control did not pass essential information about windshear reported by a preceding landing flight crew and that two flights performed go-arounds after passing over the runway threshold. The flight crew decision-making process, during the approach and landing, was deprived of this critical information.

(k) The modification of the go-around procedure by air traffic control four seconds after the Aircraft became airborne coincided with the landing gear selection to the ‘up’ position. This added to the flight crew workload as they attentively listened and the Copilot responded to the air traffic control instruction which required a change of missed approach altitude from 3,000 ft to 4,000 ft to be set. The flight crews’ concentration on their primary task of flying the Aircraft and monitoring was momentarily affected as both the FMA verification and the flight director status were missed.

Final Report: