Circumstances:

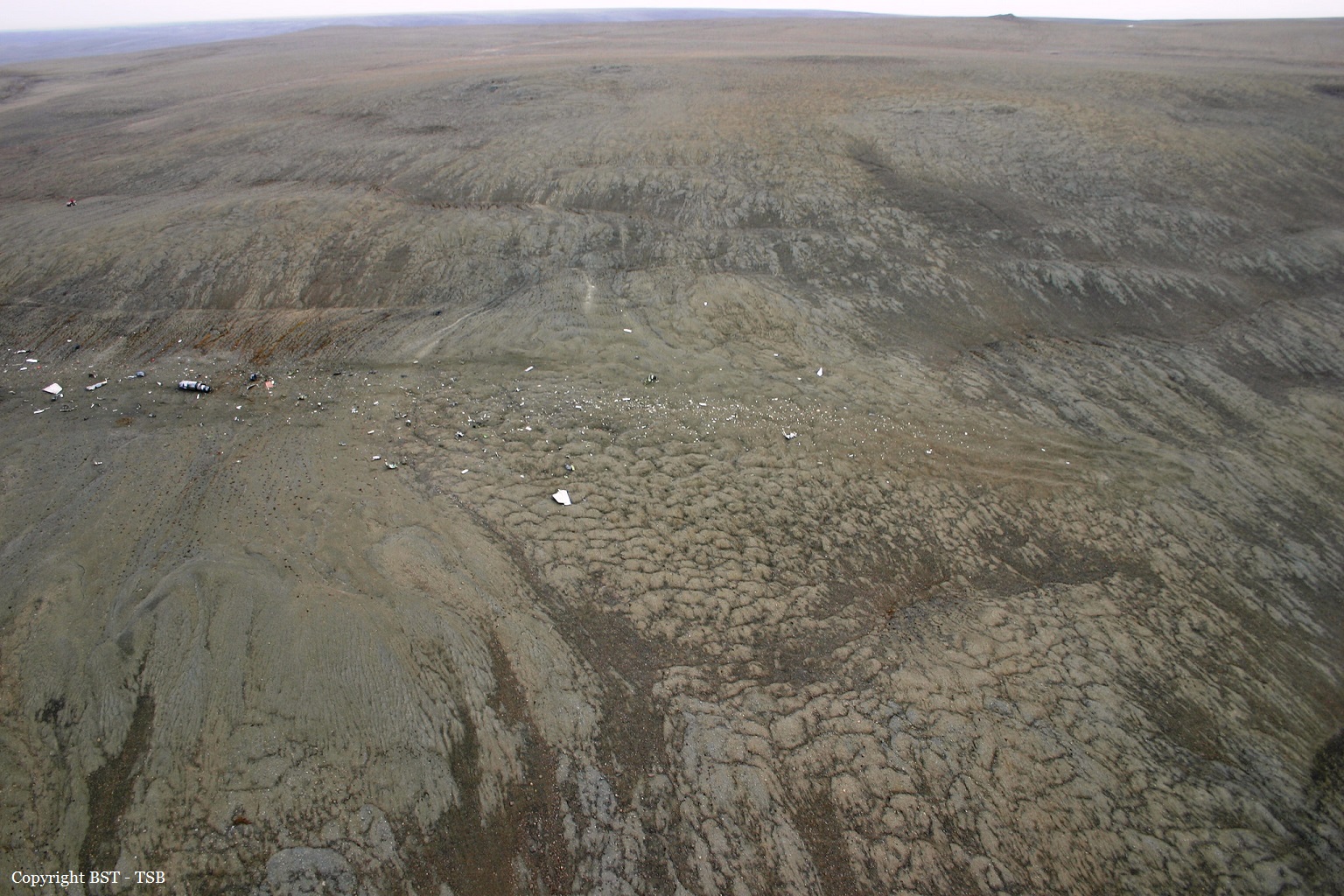

The First Air Boeing 737-210C combi aircraft departed Yellowknife (CYZF), Northwest Territories, at 1440 as First Air flight 6560 (FAB6560) on a charter flight to Resolute Bay (CYRB), Nunavut, with 11 passengers, 4 crew members, and freight on board. The instrument flight rules (IFR) flight from CYZF was flight-planned to take 2 hours and 05 minutes at 426 knots true airspeed and a cruise altitude of flight level (FL) 310. Air traffic control (ATC) cleared FAB6560 to destination via the flight-planned route: CYZF direct to the BOTER intersection, then direct to the Cambridge Bay (CB) non-directional beacon (NDB), then direct to 72° N, 100°45' W, and then direct to CYRB (Figure 1). The planned alternate airport was Hall Beach (CYUX), Nunavut. The estimated time of arrival (ETA) at CYRB was 1645. The captain occupied the left seat and was designated as the pilot flying (PF). The first officer (FO) occupied the right seat and was designated as the pilot not flying (PNF). Before departure, First Air dispatch provided the crew with an operational flight plan (OFP) that included forecast and observed weather information for CYZF, CYRB, and CYUX, as well as NOTAM (notice to airmen) information. Radar data show that FAB6560 entered the Northern Domestic Airspace (NDA) 50 nautical miles (nm) northeast of CYZF, approximately at RIBUN waypoint (63°11.4' N, 113°32.9' W) at 1450. During the climb and after leveling at FL310, the crew received CYRB weather updates from a company dispatcher (Appendix A). The crew and dispatcher discussed deteriorating weather conditions at CYRB and whether the flight should return to CYZF, proceed to the alternate CYUX, or continue to CYRB. The crew and dispatcher jointly agreed that the flight would continue to CYRB. At 1616, the crew programmed the global positioning systems (GPS) to proceed from their current en-route position direct to the MUSAT intermediate waypoint on the RNAV (GNSS) Runway (RWY) 35 TRUE approach at CYRB (Appendix B), which had previously been loaded into the GPS units by the crew. The crew were planning to transition to an ILS/DME RWY 35 TRUE approach (Appendix C) via the MUSAT waypoint. A temporary military terminal control area (MTCA) had been planned, in order to support an increase in air traffic at CYRB resulting from a military exercise, Operation NANOOK. A military terminal control unit at CYRB was to handle airspace from 700 feet above ground level (agl) up to FL200 within 80 nm of CYRB. Commencing at 1622:16, the FO made 3 transmissions before establishing contact with the NAV CANADA Edmonton Area Control Centre (ACC) controller. At 1623:29, the NAV CANADA Edmonton ACC controller cleared FAB6560 to descend out of controlled airspace and to advise when leaving FL270. The crew were also advised to anticipate calling the CYRB terminal control unit after leaving FL270, and that there would be a layer of uncontrolled airspace between FL270 and FL200. The FO acknowledged the information. FAB6560 commenced descent from FL310 at 1623:40 at 101 nm from CYRB. The crew initiated the pre-descent checklist at 1624 and completed it at 1625. At 1626, the crew advised the NAV CANADA Edmonton ACC controller that they were leaving FL260. At 1627:09, the FO subsequently called the CYRB terminal controller and provided an ETA of 1643 and communicated intentions to conduct a Runway 35 approach. Radio readability between FAB6560 and the CYRB terminal controller was poor, and the CYRB terminal controller advised the crew to try again when a few miles closer. At 1629, the crew contacted the First Air agent at CYRB on the company frequency. The crew advised the agent of their estimated arrival time and fuel request. The crew then contacted the CYRB terminal controller again, and were advised that communications were now better. The CYRB terminal controller advised that the MTCA was not yet operational, and provided the altimeter setting and traffic information for another inbound flight. The CYRB terminal controller then instructed the crew to contact the CYRB tower controller at their discretion. The FO acknowledged the traffic and the instruction to contact CYRB tower. At 1631, the crew contacted the CYRB tower controller, who advised them of the altimeter setting (29.81 inches of mercury [in. Hg]) and winds (estimated 160° true [T] at 10 knots), and instructed them to report 10 nm final for Runway 35T. The crew asked the tower controller for a runway condition report, and was advised that the runway was a little wet and that no aircraft had used it during the morning. The FO acknowledged this information. The crew initiated the in-range checklist at 1632 and completed it at 1637. At 1637, they began configuring the aircraft for approach and landing, and initiated the landing checklist. At 1638:21, FAB6560 commenced a left turn just before reaching MUSAT waypoint. At the time of the turn, the aircraft was about 600 feet above the ILS glideslope at 184 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS). The track from MUSAT waypoint to the threshold of Runway 35T is 347°T, which coincides with the localizer track for the ILS/DME RWY 35 TRUE approach. After rolling out of the left turn, FAB6560 proceeded on a track of approximately 350°T. At 1638:32, the crew reported 10 nm final for Runway 35T. The captain called for the gear to be lowered at 1638:38 and for flaps 15 at 1638:42. Airspeed at the time of both of these calls was 177 KIAS. At 1638:39, the CYRB tower controller acknowledged the crew’s report and instructed them to report 3 nm final. At 1638:46, the FO requested that the tower repeat the last transmission. At 1638:49, the tower repeated the request to call 3 nm final; the FO acknowledged the call. At this point in the approach, the crew had a lengthy discussion about aircraft navigation. At 1640:36, FAB6560 descended through 1000 feet above field elevation. Between 1640:41 and 1641:11, the captain issued instructions to complete the configuration for landing, and the FO made several statements regarding aircraft navigation and corrective action. At 1641:30, the crew reported 3 nm final for Runway 35T. The CYRB tower controller advised that the wind was now estimated to be 150°T at 7 knots, cleared FAB6560 to land Runway 35T, and added the term “check gear down” as required by the NAV CANADA Air Traffic Control Manual of Operations (ATC MANOPS) Canadian Forces Supplement (CF ATC Sup) Article 344.3. FAB6560’s response to the tower (1641:39) was cut off, and the tower requested the crew to say again. There was no further communication with the flight. The tower controller did not have visual contact with FAB6560 at any time. At 1641:51.8, as the crew were initiating a go-around, FAB6560 collided with terrain about 1 nm east of the midpoint of the CYRB runway. The accident occurred during daylight hours and was located at 74°42'57.3" N, 94°55'4.0" W, at 396 feet above mean sea level. The 4 crew members and 8 passengers were fatally injured. Three passengers survived the accident and were rescued from the site by Canadian military personnel, who were in CYRB participating in Operation NANOOK. The survivors were subsequently evacuated from CYRB on a Canadian Forces CC-177 aircraft.

Probable cause:

Findings as to causes and contributing factors:

1. The late initiation and subsequent management of the descent resulted in the aircraft turning onto final approach 600 feet above the glideslope, increasing the crew’s workload and reducing their capacity to assess and resolve the navigational issues during the remainder of the approach.

2. When the heading reference from the compass systems was set during initial descent, there was an error of −8°. For undetermined reasons, further compass drift during the arrival and approach resulted in compass errors of at least −17° on final approach.

3. As the aircraft rolled out of the turn onto final approach to the right of the localizer, the captain likely made a control wheel roll input that caused the autopilot to revert from VOR/LOC capture to MAN and HDG HOLD mode. The mode change was not detected by the crew.

4. On rolling out of the turn, the captain’s horizontal situation indicator displayed a heading of 330°, providing a perceived initial intercept angle of 17° to the inbound localizer track of 347°. However, due to the compass error, the aircraft’s true heading was 346°. With 3° of wind drift to the right, the aircraft diverged further right of the localizer.

5. The crew’s workload increased as they attempted to understand and resolve the ambiguity of the track divergence, which was incongruent with the perceived intercept angle and expected results.

6. Undetected by the pilots, the flight directors likely reverted to AUTO APP intercept mode as the aircraft passed through 2.5° right of the localizer, providing roll guidance to the selected heading (wings-level command) rather than to the localizer (left-turn command).

7. A divergence in mental models degraded the crew’s ability to resolve the navigational issues. The wings-level command on the flight director likely assured the captain that the intercept angle was sufficient to return the aircraft to the selected course; however, the first officer likely put more weight on the positional information of the track bar and GPS.

8. The crew’s attention was devoted to solving the navigational problem, which delayed the configuration of the aircraft for landing. This problem solving was an additional task, not normally associated with this critical phase of flight, which escalated the workload.

9. The first officer indicated to the captain that they had full localizer deflection. In the absence of standard phraseology applicable to his current situation, he had to improvise the go-around suggestion. Although full deflection is an undesired aircraft state requiring a go-around, the captain continued the approach.

10. The crew did not maintain a shared situational awareness. As the approach continued, the pilots did not effectively communicate their respective perception, understanding, and future projection of the aircraft state.

11. Although the company had a policy that required an immediate go-around in the event that an approach was unstable below 1000 feet above field elevation, no go-around was initiated. This policy had not been operationalized with any procedural guidance in the standard operating procedures.

12. The captain did not interpret the first officer’s statement of “3 mile and not configured” as guidance to initiate a go-around. The captain continued the approach and called for additional steps to configure the aircraft.

13. The first officer was task-saturated, and he thus had less time and cognitive capacity to develop and execute a communication strategy that would result in the captain changing his course of action.

14. Due to attentional narrowing and task saturation, the captain likely did not have a high- level overview of the situation. This lack of overview compromised his ability to identify and manage risk.

15. The crew initiated a go-around after the ground proximity warning system “sink rate” alert occurred, but there was insufficient altitude and time to execute the manoeuvre and avoid collision with terrain.

16. The first officer made many attempts to communicate his concerns and suggest a go-around. Outside of the two-communication rule, there was no guidance provided to address a situation in which the pilot flying is responsive but is not changing an unsafe course of action. In the absence of clear policies or procedures allowing a first officer to escalate from an advisory role to taking control, this first officer likely felt inhibited from doing so.

17. The crew’s crew resource management was ineffective. First Air’s initial and recurrent crew resource management training did not provide the crew with sufficient practical strategies to assist with decision making and problem solving, communication, and workload management.

18. Standard operating procedure adaptations on FAB6560 resulted in ineffective crew communication, escalated workload leading to task saturation, and breakdown in shared situational awareness. First Air’s supervisory activities did not detect the standard operating procedure adaptations within the Yellowknife B737 crew base.

Findings as to risk:

1. If standard operating procedures do not include specific guidance regarding where and how the transition from en route to final approach navigation occurs, pilots will adopt non-standard practices, which may introduce a hazard to safe completion of the approach.

2. Adaptations of standard operating procedures can impair shared situational awareness and crew resource management effectiveness.

3. Without policies and procedures clearly authorizing escalation of intervention to the point of taking aircraft control, some first officers may feel inhibited from doing so.

4. If hazardous situations are not reported, they are unlikely to be identified or investigated by a company’s safety management system; consequently, corrective action may not be taken.

5. Current Transport Canada crew resource management training standards and guidance material have not been updated to reflect advances in crew resource management training, and there is no requirement for accreditation of crew resource management facilitators/instructors in Canada. This situation increases the risk that flight crews will not receive effective crew resource management training.

6. If initial crew resource management training does not develop effective crew resource management skills, and if there is inadequate reinforcement of these skills during recurrent training, flight crews may not adequately manage risk on the flight deck.

7. If operators do not take steps to ensure that flight crews routinely apply effective crew resource management practices during flight operations, risk to aviation safety will persist.

8. Transport Canada’s flight data recorder maintenance guidance (CAR Standard 625, Appendix C) does not refer to the current flight recorder maintenance specification, and therefore provides insufficient guidance to ensure the serviceability of flight data recorders. This insufficiency increases the risk that information needed to identify and communicate safety deficiencies will not be available.

9. If aircraft are not equipped with newer-generation terrain awareness and warning systems, there is a risk that a warning will not alert crews in time to avoid terrain.

10. If air carriers do not monitor flight data to identify and correct problems, there is a risk that adaptations of standard operating procedures will not be detected.

11. Unless further action is taken to reduce the incidence of unstable approaches that continue to a landing, the risk of controlled flight into terrain and of approach and landing accidents will persist.

Other findings:

1. It is likely that both pilots switched from GPS to VHF NAV during the final portion of the in-range check before the turn at MUSAT.

2. The flight crew of FAB6560 were not navigating using the YRB VOR or intentionally tracking toward the VOR.

3. There was no interference with the normal functionality of the instrument landing system for Runway 35T at CYRB.

4. Neither the military tower nor the military terminal controller at CYRB had sufficient valid information available to cause them to issue a position advisory to FAB6560.

5. The temporary Class D control zone established by the military at CYRB was operating without any capability to provide instrument flight rules separation.

6. The delay in notification of the joint rescue coordination centre did not delay the emergency response to the crash site.

7. The NOTAMs issued concerning the establishment of the military terminal control area did not succeed in communicating the information needed by the airspace users.

8. The ceiling at the airport at the time of the accident could not be determined. The visibility at the airport at the time of the accident likely did not decrease below approach minimums at any time during the arrival of FAB6560. The cloud layer at the crash site was surface-based less than 200 feet above the airport elevation.