Circumstances:

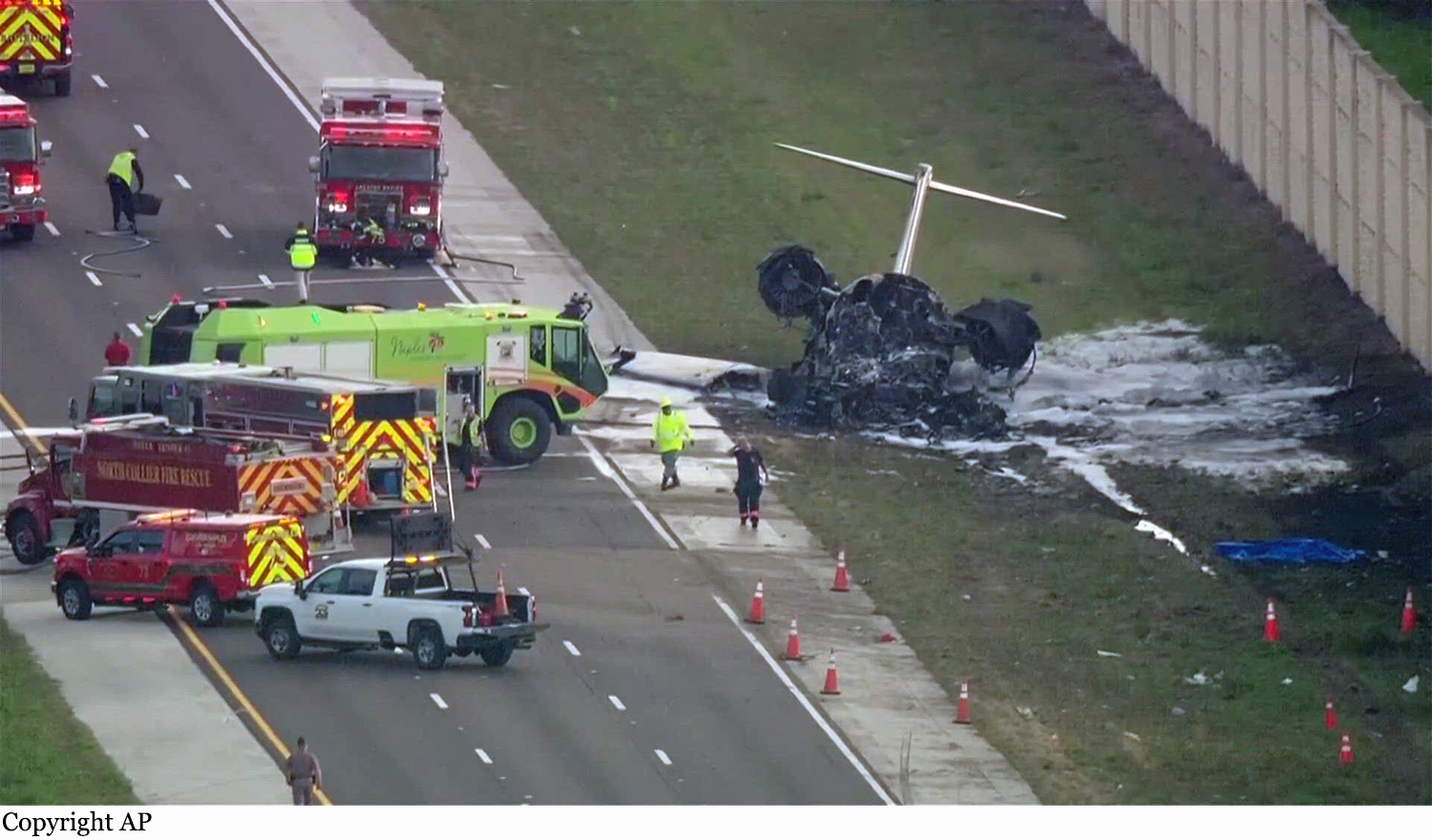

On February 9, 2024, about 1517 eastern standard time, a Bombardier Inc CL-600-2B16, N823KD, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Naples, Florida. The two airline transport pilots were fatally injured. The cabin attendant and the two passengers sustained minor injuries, and one person on the ground suffered minor injury. The airplane was operated by Ace Aviation Services (doing business as Hop-A-Jet) as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 135 on-demand passenger flight. The airplane was returning to Naples Municipal Airport (APF), Naples, Florida, from Ohio State University Airport (OSU), Columbus, Ohio, where it had flown earlier in the day. The airplane was serviced with 350 gallons of fuel before departure from OSU. Preliminary Automatic Dependent Surveillance – Broadcast (ADS-B) flight track and air traffic control (ATC) data revealed that the flight crew contacted the ATC tower at APF while on a right downwind leg of the approach to the airport and maneuvering for a 5-mile final approach to runway 23. At 1508, the tower controller cleared the flight to land. The airplane was about 6.5 miles north of APF, about 2,000 ft geometric altitude (GEO) and 166 knots groundspeed, as it turned for the base leg of the traffic pattern. A preliminary review of the data recovered from the airplane’s flight data recorder revealed that the first of three Master Warnings was recorded at 1509:33 (L ENGINE OIL PRESSURE), the second immediately following at 1509:34 (R ENGINE OIL PRESSURE), and at 1509:40 (ENGINE). The system alerted pilots with illumination of a “Master Warning” light on the glareshield, a corresponding red message on the crew alerting system page and a triple chime voice advisory (“Engine oil”). Twenty seconds later, at 1510:05, about 1,000 ft msl and 122 kts, on a shallow intercept angle for the final approach course, the crew announced, “…lost both engines… emergency… making an emergency landing” (see figure 1). The tower controller acknowledged the call and cleared the airplane to land. At 1510:12, about 900 ft and 115 knots, the crew replied, “We are cleared to land but we are not going to make the runway… ah… we have lost both engines.” There were no further transmissions from the flight crew and the ADS-B track data ended at 1510:47, directly over Interstate 75 in Naples, Florida. Dashcam video submitted to the National Transportation Safety Board captured the final seconds of the flight. The airplane descended into the camera’s view in a shallow left turn and then leveled its wings before it touched down aligned with traffic travelling the southbound lanes of Interstate 75. The left main landing gear touched down first in the center of the three lanes, and then the right main landing gear touched down in the right lane. The airplane continued through the break-down lane and into the grass shoulder area before impacting a concrete sound barrier. The airplane was obscured by dust, fire, smoke, and debris until the video ended. This information is preliminary and subject to change. After the airplane came to rest, the cabin attendant stated that she identified that the cabin and emergency exits were blocked by fire and coordinated the successful egress of her passengers and herself through the baggage compartment door in the tail section of the airplane.