Crash of an Embraer EMB-505 Phenom 300 in Houston

Date & Time:

Jul 26, 2016 at 1510 LT

Registration:

N362FX

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Scottsdale - Houston

MSN:

500-00239

YOM:

2014

Flight number:

LXJ362

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

1

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

1358.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

962

Aircraft flight hours:

1880

Circumstances:

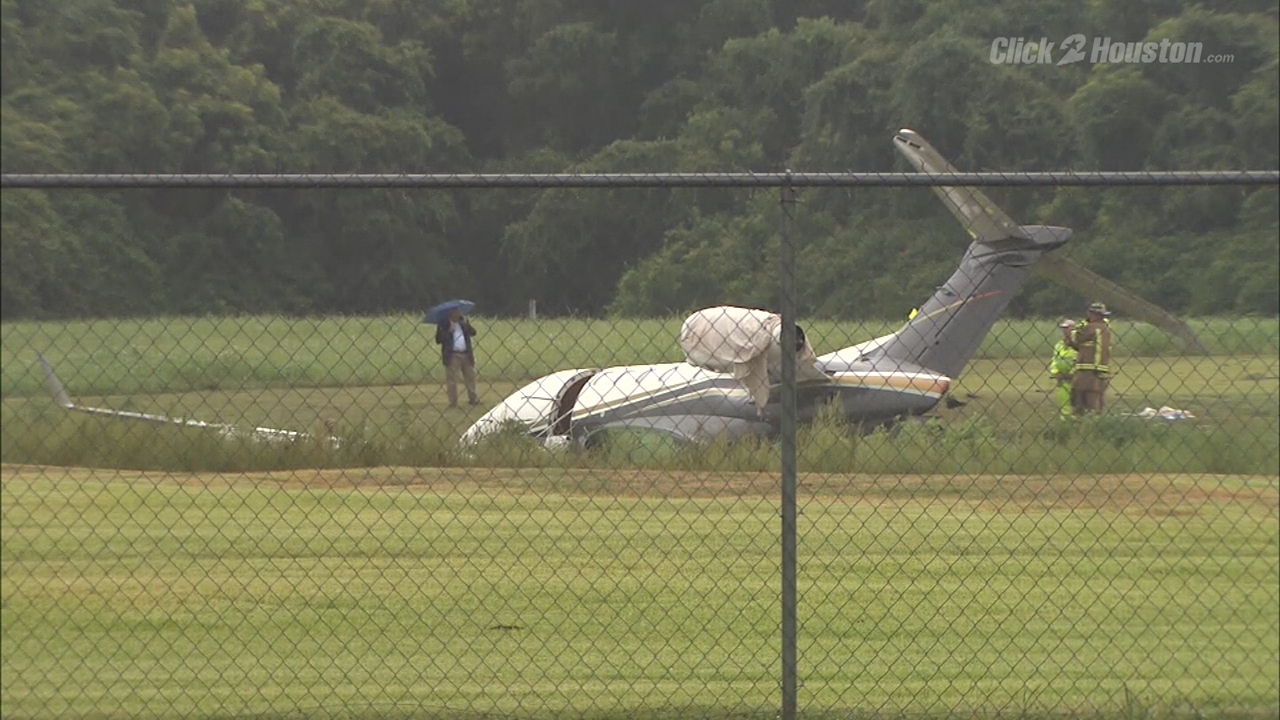

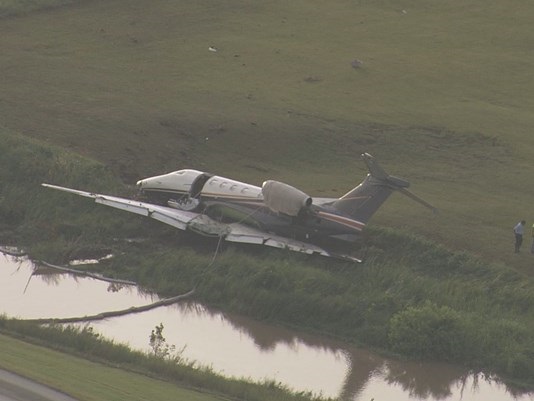

The pilot executed an instrument approach and landing in heavy rain. The airplane touched down about 21 knots above the applicable landing reference speed, which was consistent with an unstabilized approach. The airplane touched down near the displaced runway threshold about 128 kts, and both wing ground spoilers automatically deployed. The pilot reported that the airplane touched down “solidly,” and he started braking promptly, but the airplane did not slow down. The main wheels initially spun up; however, both wheel speeds subsequently decayed consistent with hydroplaning in the heavy rain conditions. When the wheel speeds did not recover, the brake control unit advised the flight crew of an anti-skid failure; the pilot recalled an anti-skid CAS message displayed at some point during the landing. The pilot subsequently activated the emergency brake system and the wheel speeds decayed. The airplane ultimately overran the departure end of the runway about 60 kts, crossed an airport perimeter road, and encountered a small creek before coming to rest. The wings had separated from, and were located immediately adjacent to, the fuselage. The pilot reported light to moderate rain began on final approach. Weather data and surveillance images indicated that heavy rain and limited visibility prevailed at the airport during the landing. Thunderstorms were active in the vicinity and the rainfall rate at the time of the accident landing was between 4.2 and 6.0 inches per hour. About 4 minutes before the accident, a surface observation recorded the visibility as 3 miles. However, 3 minutes later, the observed visibility had decreased to 3/8 mile. A review of the available information indicated that the tower controller advised the pilot of changing wind conditions and of better weather west of the airport but did not update the pilot regarding visibility along the final approach course or precipitation at the airport. The pilot stated that the rain started 2 to 3 minutes before he landed and commented that it was not the heaviest rain that he had ever landed in. The pilot was using the multifunction display and a tablet for weather radar, which showed green and yellow returns indicating light to moderate rain during the approach. He chose not to turn on the airplane’s onboard weather radar because the other two sources were not indicating severe weather. The runway exhibited skid marks beginning about 1,500 ft from the departure end and each main tire had one patch of reverted rubber wear consistent with reverted rubber hydroplaning. The main landing gear remained extended and both tires remained pressurized. The tire pressures corresponded to a minimum dynamic hydroplaning speed of about 115 kts. The airplane flight manual noted that, in the case of an antiskid failure, the main brakes are to be applied progressively and brake pressure is to be modulated as required. The emergency brake is to be used in the event of a brake failure; however, the pilot activated the emergency brake when the main brakes still functioned; although, without anti-skid protection.

Probable cause:

The airplane’s hydroplaning during the landing roll, which resulted in a runway excursion. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s continuation of an unstabilized approach, his decision to land in heavy rain conditions, and his improper use of the main and emergency brake systems. Also contributing was the air traffic controller’s failure to disseminate current airport weather conditions to the flight crew in a timely manner.

Final Report: