Crash of a Piper PA-31-325 Navajo in Grand Manan Island: 2 killed

Date & Time:

Aug 16, 2014 at 0512 LT

Registration:

C-GKWE

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Saint John - Grand Manan Island

MSN:

31-7812037

YOM:

1978

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

2

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

2

Copilot / Total hours on type:

67

Circumstances:

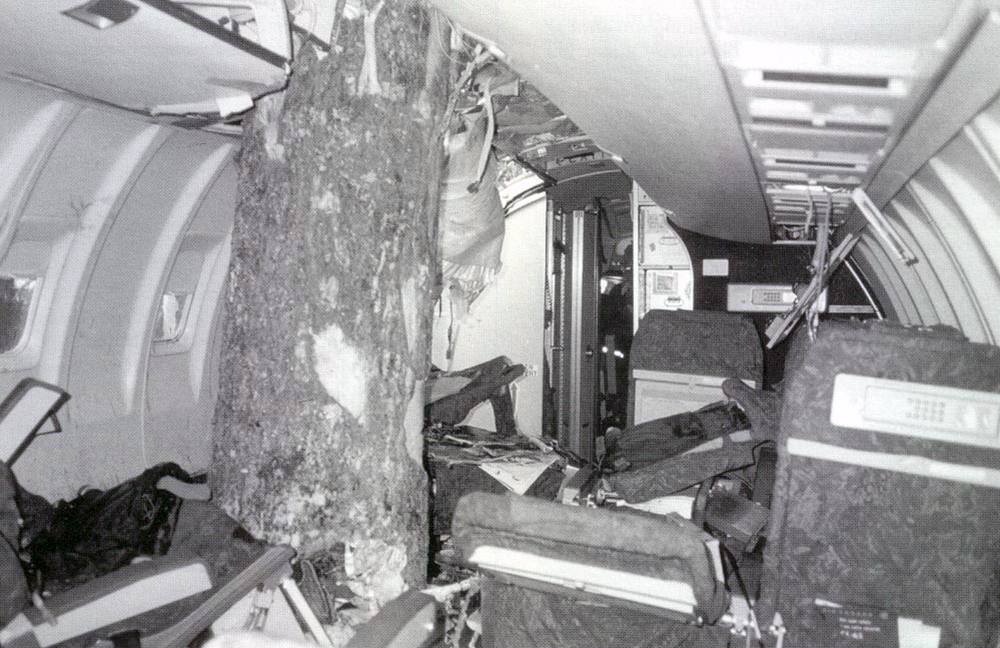

The Atlantic Charters Piper PA-31aircraft had carried out a MEDEVAC flight from Grand Manan, New Brunswick, to Saint John, New Brunswick. At 0436 Atlantic Daylight Time, the aircraft departed Saint John for the return flight to Grand Manan with 2 pilots and 2 passengers. Following an attempt to land on Runway 24 at Grand Manan Airport, the captain carried out a go-around. During the second approach, with the landing gear extended, the aircraft contacted a road perpendicular to the runway, approximately 1500 feet before the threshold. The aircraft continued straight through 100 feet of brush before briefly becoming airborne. At about 0512, the aircraft struck the ground left of the runway centreline, approximately 1000 feet before the threshold. The captain and 1 passenger sustained fatal injuries. The other pilot and the second passenger sustained serious injuries. The aircraft was destroyed; an emergency locator transmitter signal was received. The accident occurred during the hours of darkness.

Probable cause:

Findings as to causes and contributing factors:

1. The captain commenced the flight with only a single headset on board, thereby preventing a shared situational awareness among the crew.

2. It is likely that the weather at the time of both approaches was such that the captain could not see the required visual references to ensure a safe landing.

3. The first officer was focused on locating the runway and was unaware of the captain’s actions during the descent.

4. For undetermined reasons, the captain initiated a steep descent 0.56 nautical mile from the threshold, which went uncorrected until a point from which it was too late to recover.

5. The aircraft contacted a road 0.25 nautical mile short of the runway and struck terrain.

6. The paramedic was not wearing a seatbelt and was not restrained during the impact sequence.

Findings as to risk:

1. If cockpit data recordings are not available to an investigation, then the identification and communication of safety deficiencies to advance transportation safety may be precluded.

2. If crew members are unable to communicate effectively, then they are less likely to anticipate and coordinate their actions, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

3. If crew resource management training is not provided, used and continuously fostered, then there is a risk that pilots will be unprepared to avoid or mitigate crew errors encountered during flight.

4. If an actual weight and balance cannot be determined, then the aircraft may be operating outside of its approved limits, which could affect the aircraft’s performance characteristics.

5. If pre-computed weight and balance forms do not include standard items, then it increases the likelihood of omissions in weight and balance calculations, which increases the risk of inadvertently overloading or incorrectly loading the aircraft.

6. If organizations carry out a maintenance task that they consider to be elementary work and the task is not approved as an elementary work task, then there is a risk that the aircraft will not conform to its type design, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

7. If individuals are performing maintenance tasks for which they have not received approved training, then there is a risk that the task will not be performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

8. If components are not installed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, then occupants are at a greater risk of injury or death during an incident or accident if these components are not properly secured.

9. If organizations do not record when maintenance is carried out, then the proper completion of tasks cannot be confirmed, and there is a risk that the aircraft will not conform to its type design, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

10. If an aircraft is modified without regulatory approval and without supporting documentation, then the aircraft is not in compliance with all applicable standards of airworthiness, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

11. If an operator undertakes unapproved changes to a supplemental type certificate, then there is a risk that the aircraft will not be airworthy, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

12. If organizations do not use modern safety management practices, then there is an increased risk that hazards will not be identified and risks mitigated.

13. If Transport Canada does not adopt a balanced approach that combines thorough inspections for compliance with audits of safety management processes, unsafe operating practices may not be identified, thereby increasing the risk of accidents.

14. If organizations contract aviation companies to provide a service with which the organizations are not familiar, then there is an increased risk that safety deficiencies will go unnoticed, which could jeopardize the safety of the organizations’ employees.

15. If passengers are not provided with a regular safety briefing, then there is an increased risk that they will not use the available safety equipment or be able to perform necessary emergency functions in a timely manner to avoid injury or death.

16. If passengers are not properly restrained, then there is an increased risk of injuries and death to those passengers and the other occupants in the event of an accident.

17. If carry-on baggage, equipment or cargo is not restrained, then occupants are at a greater risk of injury or death if these items become projectiles in a crash.

18. If carry-on baggage, equipment or cargo is not restrained, then there is an increased risk that the occupants’ access to normal and emergency exits, and to safety equipment, will be completely or partially blocked.

19. If pilots continue an approach below published minimum descent altitudes without seeing the required visual references, then there is a risk of collision with terrain and/or obstacles.

20. If current charts and databases are not used, then navigational accuracy and obstacle avoidance cannot be assured.

21. If GPS (global positioning system) approaches are conducted without the approved Operations Specification, then there is a risk that the pilot’s training and knowledge will be inadequate to safely conduct the approach.

22. If medical symptoms/conditions are not reported to Transport Canada, then it negates some of the safety benefit of examinations and increases the risk that pilots will continue to fly with a medical condition that poses a risk to safety.

Other findings:

1. The pilot who installed the air ambulance system did not have approved training, nor was the pilot approved to carry out elementary work.

2. Atlantic Charters was not approved to install the air ambulance system as an elementary work task.

3. Atlantic Charters’ pre-computed weight and balance form did not include a line item to indicate nacelle fuel.

4. The semi-annual safety training offered to paramedics in lieu of safety briefings prior to flights did not meet regulatory requirements.

1. The captain commenced the flight with only a single headset on board, thereby preventing a shared situational awareness among the crew.

2. It is likely that the weather at the time of both approaches was such that the captain could not see the required visual references to ensure a safe landing.

3. The first officer was focused on locating the runway and was unaware of the captain’s actions during the descent.

4. For undetermined reasons, the captain initiated a steep descent 0.56 nautical mile from the threshold, which went uncorrected until a point from which it was too late to recover.

5. The aircraft contacted a road 0.25 nautical mile short of the runway and struck terrain.

6. The paramedic was not wearing a seatbelt and was not restrained during the impact sequence.

Findings as to risk:

1. If cockpit data recordings are not available to an investigation, then the identification and communication of safety deficiencies to advance transportation safety may be precluded.

2. If crew members are unable to communicate effectively, then they are less likely to anticipate and coordinate their actions, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

3. If crew resource management training is not provided, used and continuously fostered, then there is a risk that pilots will be unprepared to avoid or mitigate crew errors encountered during flight.

4. If an actual weight and balance cannot be determined, then the aircraft may be operating outside of its approved limits, which could affect the aircraft’s performance characteristics.

5. If pre-computed weight and balance forms do not include standard items, then it increases the likelihood of omissions in weight and balance calculations, which increases the risk of inadvertently overloading or incorrectly loading the aircraft.

6. If organizations carry out a maintenance task that they consider to be elementary work and the task is not approved as an elementary work task, then there is a risk that the aircraft will not conform to its type design, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

7. If individuals are performing maintenance tasks for which they have not received approved training, then there is a risk that the task will not be performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

8. If components are not installed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, then occupants are at a greater risk of injury or death during an incident or accident if these components are not properly secured.

9. If organizations do not record when maintenance is carried out, then the proper completion of tasks cannot be confirmed, and there is a risk that the aircraft will not conform to its type design, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

10. If an aircraft is modified without regulatory approval and without supporting documentation, then the aircraft is not in compliance with all applicable standards of airworthiness, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

11. If an operator undertakes unapproved changes to a supplemental type certificate, then there is a risk that the aircraft will not be airworthy, which could jeopardize the safety of flight.

12. If organizations do not use modern safety management practices, then there is an increased risk that hazards will not be identified and risks mitigated.

13. If Transport Canada does not adopt a balanced approach that combines thorough inspections for compliance with audits of safety management processes, unsafe operating practices may not be identified, thereby increasing the risk of accidents.

14. If organizations contract aviation companies to provide a service with which the organizations are not familiar, then there is an increased risk that safety deficiencies will go unnoticed, which could jeopardize the safety of the organizations’ employees.

15. If passengers are not provided with a regular safety briefing, then there is an increased risk that they will not use the available safety equipment or be able to perform necessary emergency functions in a timely manner to avoid injury or death.

16. If passengers are not properly restrained, then there is an increased risk of injuries and death to those passengers and the other occupants in the event of an accident.

17. If carry-on baggage, equipment or cargo is not restrained, then occupants are at a greater risk of injury or death if these items become projectiles in a crash.

18. If carry-on baggage, equipment or cargo is not restrained, then there is an increased risk that the occupants’ access to normal and emergency exits, and to safety equipment, will be completely or partially blocked.

19. If pilots continue an approach below published minimum descent altitudes without seeing the required visual references, then there is a risk of collision with terrain and/or obstacles.

20. If current charts and databases are not used, then navigational accuracy and obstacle avoidance cannot be assured.

21. If GPS (global positioning system) approaches are conducted without the approved Operations Specification, then there is a risk that the pilot’s training and knowledge will be inadequate to safely conduct the approach.

22. If medical symptoms/conditions are not reported to Transport Canada, then it negates some of the safety benefit of examinations and increases the risk that pilots will continue to fly with a medical condition that poses a risk to safety.

Other findings:

1. The pilot who installed the air ambulance system did not have approved training, nor was the pilot approved to carry out elementary work.

2. Atlantic Charters was not approved to install the air ambulance system as an elementary work task.

3. Atlantic Charters’ pre-computed weight and balance form did not include a line item to indicate nacelle fuel.

4. The semi-annual safety training offered to paramedics in lieu of safety briefings prior to flights did not meet regulatory requirements.

Final Report: