Circumstances:

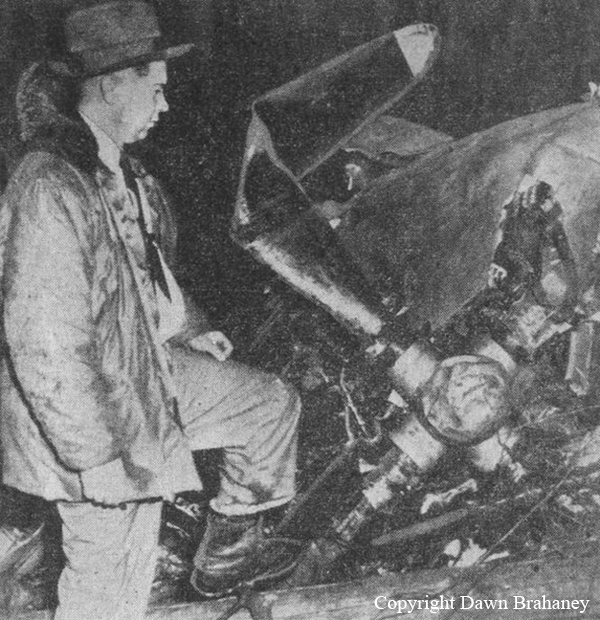

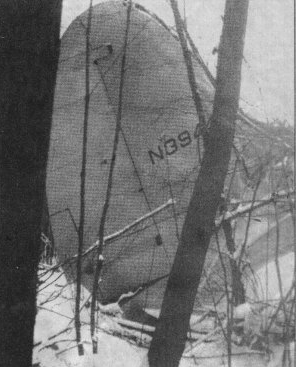

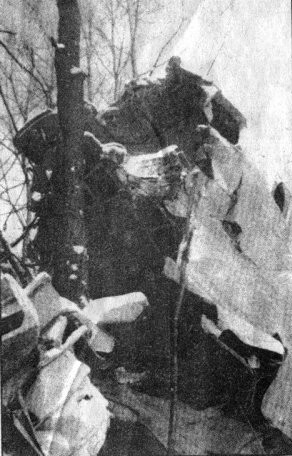

Pan American's Flight 131 departed from Bermuda at 1358, September 20, 1947, with 36 passengers and a crew of 5. The take-off and climb to the cruising altitude of 8,000 feet were normal, and the flight proceeded on course to La Guardia Field, New York, for a period of 3 hours without incident Between 1650 and 1655, about 225 statute miles from destination, Warren Robinson, the first officer, noticed a fluctuation in fuel pressure for engines 1 and 2 Seconds later, the left auxiliary fuel tank quantity gauge dropped to zero, the fuel pressure warning light flashed on, and the No 1 engine faltered To insure a positive fuel supply for all engines Mr Robinson immediately turned the fuel selector valves for all engines to their respective main tanks, 2 following which all engines operated normally. Mr Robinson then transferred fuel from the right auxiliary tank to the left auxiliary tank so that they would contain equal amounts, which was 40 gallons each according to the fuel quantity gauges after completion of the operation A few minutes later Mr Robinson noticed that the right auxiliary fuel gauge indicated not 40 gallons, but 100, and that it was visibly increasing even though no fuel was at that time being transferred The No. 3 main fuel tank gauge then dropped to zero, and the fuel pressure for the No 4 engine started to fluctuate. Alarmed by what now appeared to be a serious malfunction in the right side of the fuel system, Mr Robinson operated all engines from the left main tanks (1 and 2), turning on all the cross feed valves, and the booster pumps for main tanks 1 and 2. The flight had by this time reached position "Baker," a point on course and a distance of 212 statue miles from La Guardia This check point was regularly used by Pan American on the route from Bermuda to La Guardia, and was established by reference to precomputed radio bearings Flight Radio Officer Rea was instructed to call Captain Carl Gregg, who was eating lunch in the passengers cabin, to the cockpit. The captain, unable to account for what appeared to be a total loss of fuel in the right main tanks, tried to operate engines 3 and 4 from their respective mains. Shortly after, the fuel pressure for both these engines dropped, the fuel pressure warning lights came on, and engines 3 and 4 lost power. Other combinations of fuel valve settings were tried during the next few minutes, but power could not be restored to engines 3 and 4 The "fasten seat belt" sign was turned on, rated power was applied to engines 1 and 2, and a descent of 200 to 300 feet per minute started. Two minutes later the fire warning light flashed on for engine 4 The flight radio officer was sent to the passengers cabin to see if any signs of fire from this engine were visible He saw none from engine 4, but he did see smoke trailing from engine 3. By the time Mr Rea returned to the cockpit, Captain Gregg noticed the smell of burning rubber, and furthermore, that the fire warning light for engine 3 was also on. No flames from either engine, however, were visible. Standard fire fighting methods were followed to control the fire in the No. 3 nacelle. The propeller was feathered, all fluids into the engine were closed at the emergency shutoff valves, and the C02 gas bottle was discharged. The fire warning light then went out. Since there was no visible indication of fire in engine 4, the C02 gas bottle was not discharged. As a precautionary measure, however, the shutoff valves for all fluids into the engine were closed, and an attempt made to feather the propeller But, the propeller would not feather, and continued to windmill. At 1712, shortly after Mr. Rea transmitted to the company the flight's position as "Baker", a loud noise from the right side of the airplane was heard, and simultaneously the green right landing gear light came on. Through the drift sight the crew could see the right outboard tire burning, and a landing gear bungee cable hanging slack. All attempts to raise the right gear were unsuccessful, and it was found that with the right gear down, and with both right engines "out" that an air speed of 125 miles per hour was required to maintain directional control. At 1730, engine 4 stopped windmilling, having seized from lack of lubrication By 1745, altitude had been lost to about 1,000 feet, and over 100 statute miles remained to destination. Full take-off power was applied to engines 1 and 2 in an attempt to hold the remaining altitude. A report had been transmitted to the company at 1729 that the fires in engines 3 and 4 were believed to be out, and at 1740, the company had been advised that the flight was at 2,000 feet still descending All radio contacts with Pan American at La Guardia throughout the course of this emergency were accomplished through Eastern Air Lines' radio on the frequency 8565 kcs. Mr. Rea attempted to secure a fix on "CW" 3 from the U. S. Coast Guard, using the distress frequency of 8280 kcs. Because of an extreme amount of "CW" interference on this frequency only one station was actually contacted. This was NMR, the Coast Guard station in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Even this contact was not entirely satisfactory, and no radio bearing from it was ever received. The radio equipment was accordingly returned to the frequency of 8565 kcs, the established channel of communication, for further radiophone contact with New York. No call was ever made on the international distress frequency of 500 kcs., or over any of the "VHF" equipment on board. By 1800, altitude had been lost to 800 feet, and still over 50 statute miles remained to destination. Preparations were made for "ditching". The passengers were instructed in the use of life jackets, and in emergency water landing procedures. The life rafts were moved so as to be easily accessible from the main cabin door. Celluloid protective coverings were removed from all the emergency exit handles Clothing was loosened, and seat belts tightened. Flight Radio Officer Rea broadcasted "blind" on the frequency 8280 kcs., reporting the position of the flight to be 40-00 degrees north and 73-10 degrees west. From this point on only a small gradual loss of altitude was experienced. Captain Gregg decided to attempt to reach and land at Floyd Bennett Field, and was advised through Eastern Air Lines' radio that runway one would be available. New York Air Traffic Control had been alerted through Eastern Air Lines' radio of the emergency, and they in turn had called Coast Guard search and rescue. Coast Guard, Army, and Navy rescue equipment was dispatched, and as Flight 131 approached the coast, the crew observed other aircraft and surface vessels proceeding out to meet them. At 1815, approximately 15 statute miles from Floyd Bennett Field, the flight had descended to an altitude of 400 feet. Full available power was now applied to engines 1 and 2, and the flight was able to not only hold, but even gain a slight amount of altitude, Four to five minutes later, 1820, throttles were retarded to take-off power and the aircraft maneuvered into a position for a straight-in landing approach on runway one. The aircraft was set down 775 feet from the south end of runway one, wheels up. During the course of the crash landing the No. 1 propeller was torn from the engine, the propeller dome becoming embedded in the No. 2 main fuel tank. The spilled gasoline was ignited by sparks generated as the aircraft skidded 2,167 feet on the concrete runway to a stop U. S. Navy fire and crash equipment had been previously deployed along runway one which allowed the Navy's crash personnel to bring the fire quickly under control, and to assist the passengers and crew to deplane without injury.