Crash of a McDonnell Douglas MD-88 in LaGuardia

Date & Time:

Mar 5, 2015 at 1102 LT

Registration:

N909DL

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Atlanta – New York

MSN:

49540/1395

YOM:

1987

Flight number:

DL1086

Crew on board:

5

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

125

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

11000.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

3000

Aircraft flight hours:

71196

Aircraft flight cycles:

54865

Circumstances:

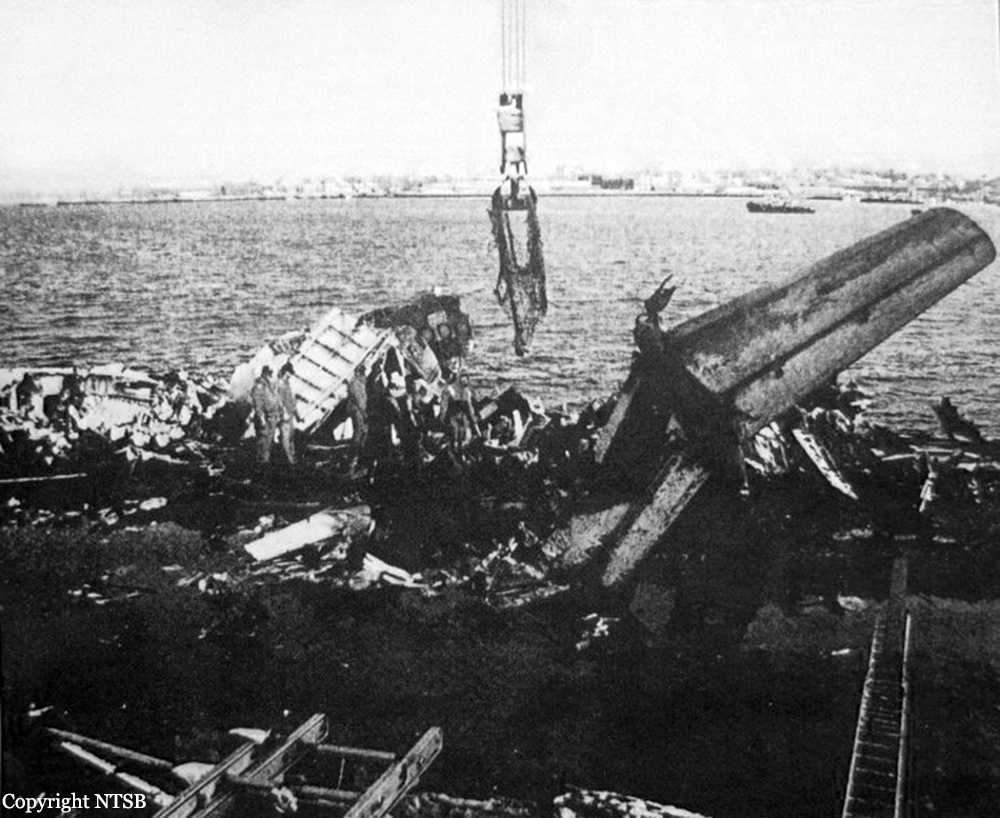

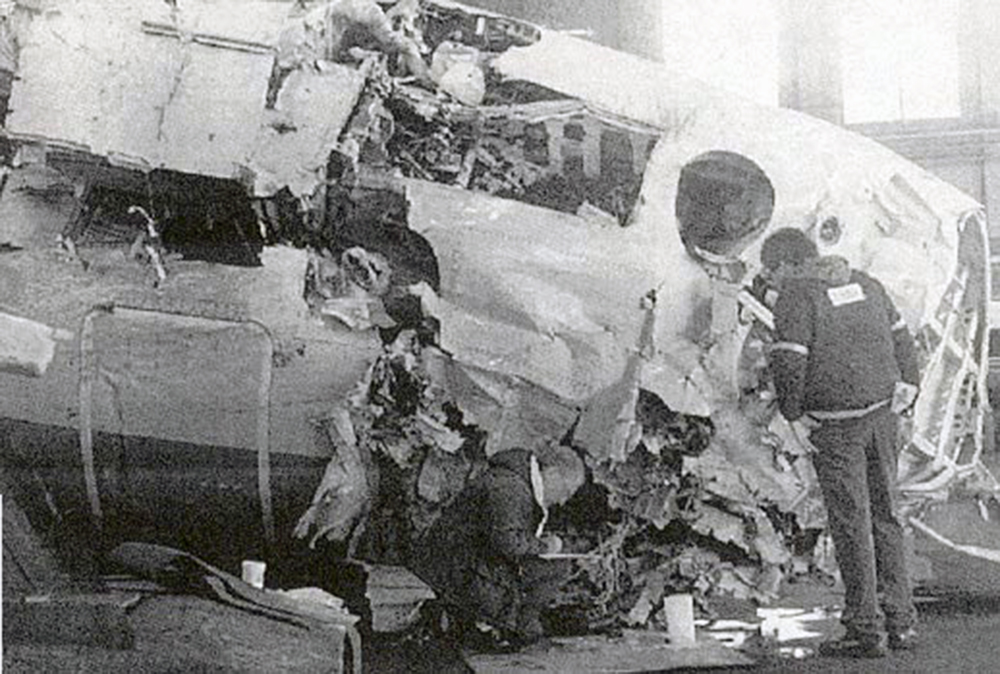

The aircraft was landing on runway 13 at LaGuardia Airport (LGA), New York, New York, when it departed the left side of the runway, contacted the airport perimeter fence, and came to rest with the airplane’s nose on an embankment next to Flushing Bay. The 2 pilots, 3 flight attendants, and 98 of the 127 passengers were not injured; the other 29 passengers received minor injuries. The airplane was substantially damaged. Flight 1086 was a regularly scheduled passenger flight from Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, Atlanta, Georgia, operating under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121. An instrument flight rules flight plan had been filed. Instrument meteorological conditions prevailed at the time of the accident. The captain and the first officer were highly experienced MD-88 pilots. The captain had accumulated about 11,000 hours, and the first officer had accumulated about 3,000 hours, on the MD-88/-90. In addition, the captain was previously based at LGA and had made many landings there in winter weather conditions. The flight crew was concerned about the available landing distance on runway 13 and, while en route to LGA, spent considerable time analyzing the airplane’s stopping performance. The flight crew also requested braking action reports about 45 and 35 minutes before landing, but none were available at those times because of runway snow clearing operations. The unavailability of braking actions reports and the uncertainty about the runway’s condition created some situational stress for the captain, who was the pilot flying. After runway 13 became available for arriving airplanes, the flight crews of two preceding airplanes (which landed on the runway about 16 and 8 minutes before the accident landing) reported good braking action on the runway, so the flight crew expected to see at least some of the runway’s surface after the airplane broke out of the clouds. However, the flight crew saw that the runway was covered with snow, which was inconsistent with their expectations based on the braking action reports and the snow clearing operations that had concluded less than 30 minutes before the airplane landed. The snowier-than-expected runway, along with its relatively short length and the presence of Flushing Bay directly off the departure end of the runway, most likely increased the captain’s concerns about his ability to stop the airplane within the available runway distance, which exacerbated his situational stress. The captain made a relatively aggressive reverse thrust input almost immediately after touchdown. Reverse thrust is one of the methods that pilots use to decelerate the airplane during the landing roll. Reverse thrust settings are expressed as engine pressure ratio (EPR) values, which are measurements of engine power (the ratio of the pressure of the gases at the exhaust compared with the pressure of the air entering the inlet). Both pilots were aware that 1.3 EPR was the target setting for contaminated runways.As reverse thrust EPR was rapidly increasing, the captain’s attention was focused on other aspects of the landing, which included steering the airplane to counteract a slide to the left and ensuring that the spoilers had deployed (a necessary action for the autobrakes to engage). The maximum EPR values reached during the landing were 2.07 on the left engine and 1.91 on the right engine, which were much higher than the target setting of 1.3 EPR. These high EPR values likely resulted from a combination of the captain’s stress; his relatively aggressive reverse thrust input; and operational distractions, including the airplane’s continued slide to the left despite the captain’s efforts to steer it away from the snowbanks alongside the runway. All of these factors reduced the captain’s monitoring of EPR indications. The high EPR values caused rudder blanking (which occurs on MD-80 series airplanes when smooth airflow over the rudder is disrupted by high reverse thrust) and a subsequent loss of aerodynamic directional control. Although the captain stowed the thrust reversers and applied substantial right rudder, right nosewheel steering, and right manual braking, the airplane’s departure from the left side of the runway could not be avoided because directional control was regained too late to be effective.

Probable cause:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the captain’s inability to maintain directional control of the airplane due to his application of excessive reverse thrust, which degraded the effectiveness of the rudder in controlling the airplane’s heading. Contributing to the accident were the captain’s:

- situational stress resulting from his concern about stopping performance and

- attentional limitations due to the high workload during the landing, which prevented him from immediately recognizing the use of excessive reverse thrust.

- situational stress resulting from his concern about stopping performance and

- attentional limitations due to the high workload during the landing, which prevented him from immediately recognizing the use of excessive reverse thrust.

Final Report: