Crash of a PZL-Mielec AN-28 in Østre Æra

Date & Time:

Jul 16, 2004 at 1324 LT

Registration:

YL-KAB

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Østre Æra - Østre Æra

MSN:

1AJ009-15

YOM:

1991

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

400.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

1000

Circumstances:

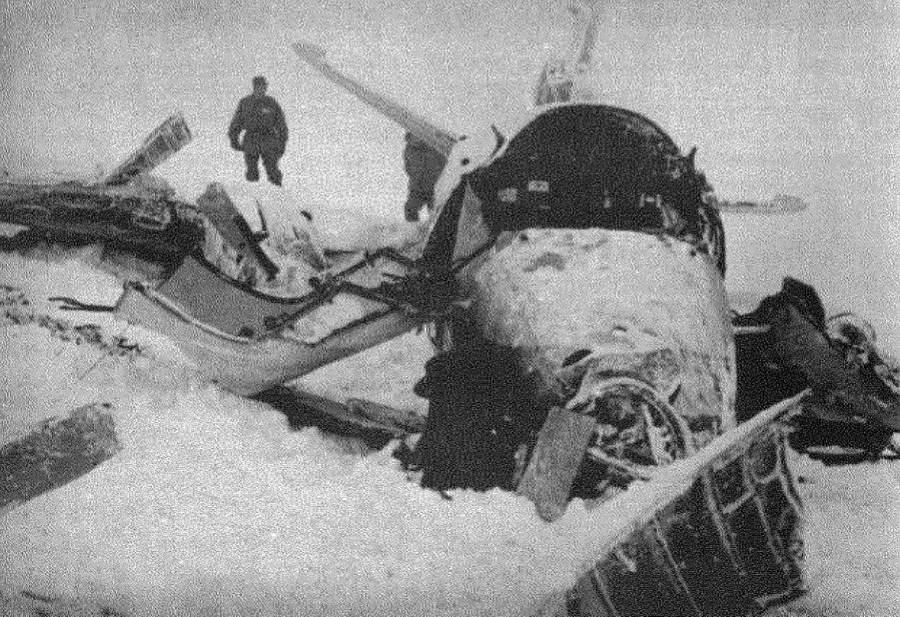

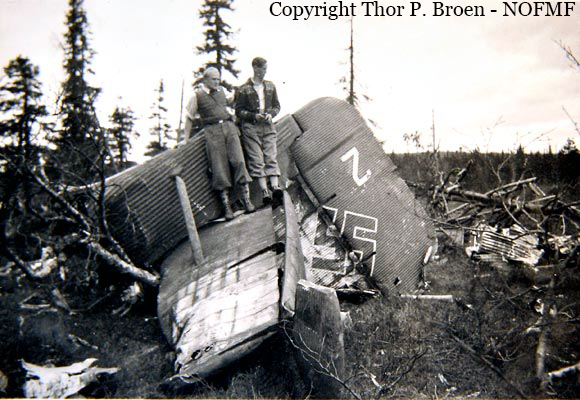

Two aircraft of type AN-28, operated by Rigas Aeroklubs Latvia, were dropping parachutists at the National Parachute Sport Centre, Østre Æra airstrip in Østerdalen. The company had had a great deal of experience with this type of operations, and had been carrying out parachute drops in Norway each summer for the last 9 years. They had brought their own licensed aircraft technicians with them to Østre Æra. On Friday morning, 16 July 2004, the weather conditions were good when the flights started. The crew of YL-KAB, which comprised two experienced pilots, were rested after a normal night's sleep. They first performed six routine drop flights. After stopping to fill up with fuel, normal preparations were made for the next flight with 20 parachutists who were to jump in two groups of 10. The seventh departure was carried out at time 1305. The Commander asked for and was given clearance by the air traffic control service to climb to flight level FL150 (15,000 ft equivalent to approx. 4,500 metres). The parachutists were then dropped from that altitude. The first drop of 10 parachutists was made on a southerly course above the airstrip, and the aircraft continued on that course for a short time before turning through 180° and getting ready for the next drop at the same location on a northerly course. A large cumulonimbus cloud (CB), with precipitation, had approached the airfield from the north at this time. To reach the drop zone above the runway, the aircraft had to fly close to this cloud. The aircraft was not equipped with weather radar. The last parachutists to leave the aircraft were in a tandem jump that was being filmed on video. The film showed that the parachutists became covered in a layer of white ice within 2-3 seconds of leaving the aircraft. The ice on the parachutists only thawed once they had descended to lower altitudes where the air temperature was above zero. Once the parachutists had jumped, the aircraft was positioned close to the CB cloud at a low cruising speed. They were exposed to moderate turbulence from the cloud. The Commander, who was the PF (pilot flying), started a sudden 90° turn to the left while also reducing engine power to flight idle in order to avoid the CB cloud and return to Østre Æra to land. At this point, the First Officer who was PNF (pilot not flying) observed that ice had formed on the front windshield, and he chose to switch on the anti-icing system. He did this without informing the PF. A few seconds later both engines stopped, and both propellers automatically adopted the feathered position. The pilots had not noticed any technical problems with the aircraft engines before they failed. During the descent, the PNF, on the PF's orders, carried out a series of start-up attempts with reference to the checklist/procedure they had available in the cockpit. The engines would not start and the PF made a decision and prepared to carry out an emergency landing at Østre Æra without engines. The runway at Østre Æra is 600 m long and 10 m wide. The surrounding area is covered by dense coniferous forest and they had no alternative landing areas within reach. Because they were without engine power, there was no hydraulic power to operate the aircraft's flaps. This meant that the speed of the aircraft had to be kept relatively high, approx. 160-180 km/h. The final approach was further complicated because the PF had to avoid the last 10 parachutists who were still in the air and who were steering towards a landing area just beside the airstrip. The PF first positioned the aircraft on downwind on a southerly course west of the airfield, in order then to make a left turn to final on runway 01. The landing took place around halfway down the runway, at a faster speed than normal - according to the Commander's explanation approximately 160-170 km/h. The PF braked using the wheel brakes, but when he realized that he would not be able to stop on the length of runway remaining, he ceased braking. He knew that the terrain directly on the extension to the runway was rough, and chose to use the aircraft's remaining speed to lift it off the ground and to alter course a little to the right. The aircraft passed over the approx. 2.5 m high embankment in the transition between the runway level and the higher marshy plateau surrounding the northern runway area, see Figure 1. The aircraft ran approx. 230 m in ground effect before landing on its heels in the flat marshy area north of the airfield. After around 60 m of roll-out, the nose wheel and the aircraft's nose struck a ditch and the aircraft turned over lengthways. It came to rest upside down with its nose section pointing towards the landing strip.

Probable cause:

The experienced Commander assessed the distance to the cumulonimbus cloud as sufficient to allow the drop to be carried out, and expected that they would then rapidly make their way out of the exposed area. It appeared, however, that problems arose when the aircraft was exposed to turbulence and icing from the cloud. The AIBN believes the limits of the engines' operational range were exceeded since the anti-icing system was switched on while the power output from the engines was low, in combination with low airspeed, turbulence and sudden manoeuvring. At that, both engines stopped, and the propellers were automatically feathered. The AIBN believes the engines would not restart because the Feathering Levers were not moved from the forward to the rear position and forward again, as is required after automatic feathering. The manufacturer has pointed out that, according to the procedures, the crew should have refrained from restart attempts and prioritized preparing for the emergency landing. AIBN acknowledges this view, taken into consideration that the crew had not received necessary training and that no suitable checklists existed. On the other hand, it is the AIBN’s opinion that this strategy may appear too passive in a real emergency. If the flight is over rugged mountain terrain or over water, an emergency landing may have fatal outcome. Provided there is sufficient time, and that crew cooperation is organised in such a way that it does not jeopardise the conduct of safe flight, a successful restart may prevent an accident. The AIBN cannot rule out the possibility that the crew's ability to make a correct assessment of the situation was reduced due to oxygen deficiency. Low oxygen-saturation in the brain would first lead to generally reduced mental capacity. In particular, this applies to the capacity to do several things simultaneously and the ability to remember. These are factors that are crucial when a pilot in a stressful situation has to choose the best solution to a problem, and the negative effects will appear more rapidly the older a person is. The fact that the First Officer switched on the anti-icing system without asking the Commander first, indicates that crew collaboration was not functioning at its best. The AIBN believes that the crew, after having entered this difficult situation, carried out a satisfactory emergency landing under very demanding conditions. The fact of the parachutists being within the approach sector made the scenario more complex, and a landing ahead of the threshold had to be avoided. With the flaps non-functional, it is understandable that the speed was high and the touchdown point not optimal. The fact that the Commander got the aircraft into the air again and landed on the higher marshy plateau, was probably crucial to the outcome. Continued braking would have resulted in the aircraft running into the earth embankment at relatively high residual speed, and it is doubtful whether the crew would have survived. A safety recommendation is being put forward in connection with this. Even if allowances are made for parachuting being a special type of operation that often takes place under the direction of a club, the AIBN believes that this investigation has uncovered several issues that cannot be considered to be satisfactory when compared to the safety standard on which they ought to be based. A user-friendly checklist system in the cockpit which is used during normal operations, in emergency situations and during flight training would increase the probability of the aircraft being operated in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. It is of great importance that pilots are sufficiently trained and experienced to carry out appropriate emergency procedures. It is assumed, however, that the new regulation concerning civil parachute jumping will contribute to increased levels of safety, and the AIBN sees no need to recommend any further measures.

Final Report: