Circumstances:

On 2 September 1998, Swissair Flight 111 departed New York, United States of America, at 2018 eastern daylight savings time on a scheduled flight to Geneva, Switzerland, with 215 passengers and 14 crew members on board. About 53 minutes after departure, while cruising at flight level 330, the flight crew smelled an abnormal odour in the cockpit. Their attention was then drawn to an unspecified area behind and above them and they began to investigate the source. Whatever they saw initially was shortly thereafter no longer perceived to be visible. They agreed that the origin of the anomaly was the air conditioning system. When they assessed that what they had seen or were now seeing was definitely smoke, they decided to divert. They initially began a turn toward Boston; however, when air traffic services mentioned Halifax, Nova Scotia, as an alternative airport, they changed the destination to the Halifax International Airport. While the flight crew was preparing for the landing in Halifax, they were unaware that a fire was spreading above the ceiling in the front area of the aircraft. About 13 minutes after the abnormal odour was detected, the aircraft’s flight data recorder began to record a rapid succession of aircraft systems-related failures. The flight crew declared an emergency and indicated a need to land immediately. About one minute later, radio communications and secondary radar contact with the aircraft were lost, and the flight recorders stopped functioning. About five and one-half minutes later, the aircraft crashed into the ocean about five nautical miles southwest of Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia, Canada. The aircraft was destroyed and there were no survivors.

Probable cause:

Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors

1. Aircraft certification standards for material flammability were inadequate in that they allowed the use of materials that could be ignited and sustain or propagate fire. Consequently, flammable material propagated a fire that started above the ceiling on the right side of the cockpit near the cockpit rear wall. The fire spread and intensified rapidly to the extent that it degraded aircraft systems and the cockpit environment, and ultimately led to the loss of control of the aircraft.

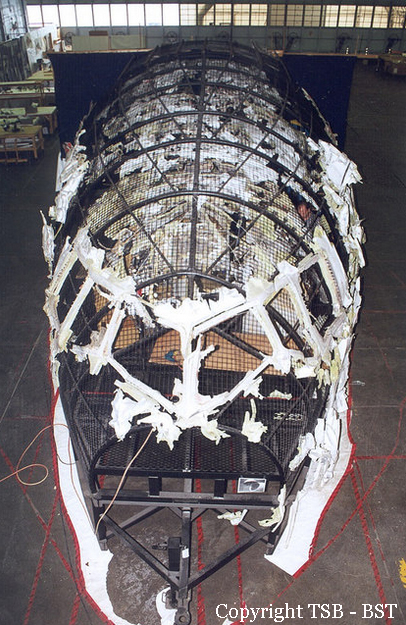

2. Metallized polyethylene terephthalate (MPET)–type cover material on the thermal acoustic insulation blankets used in the aircraft was flammable. The cover material was most likely the first material to ignite, and constituted the largest portion of the combustible materials that contributed to the propagation and intensity of the fire.

3. Once ignited, other types of thermal acoustic insulation cover materials exhibit flame propagation characteristics similar to MPET-covered insulation blankets and do not meet the proposed revised flammability test criteria. Metallized polyvinyl fluoride–type cover material was installed in HB-IWF and was involved in the in-flight fire.

4. Silicone elastomeric end caps, hook-and-loop fasteners, foams, adhesives, and thermal acoustic insulation splicing tapes contributed to the propagation and intensity of the fire.

5. The type of circuit breakers (CB) used in the aircraft were similar to those in general aircraft use, and were not capable of protecting against all types of wire arcing events. The fire most likely started from a wire arcing event.

6. A segment of in-flight entertainment network (IFEN) power supply unit cable (1-3791) exhibited a region of resolidified copper on one wire that was caused by an arcing event. This resolidified copper was determined to be located near manufacturing station 383, in the area where the fire most likely originated. This arc was likely associated with the fire initiation event; however, it could not be determined whether this arced wire was the lead event.

7. There were no built-in smoke and fire detection and suppression devices in the area where the fire started and propagated, nor were they required by regulation. The lack of such devices delayed the identification of the existence of the fire, and allowed the fire to propagate unchecked until it became uncontrollable.

8. There was a reliance on sight and smell to detect and differentiate between odour or smoke from different potential sources. This reliance resulted in the misidentification of the initial odour and smoke as originating from an air conditioning source.

9. There was no integrated in-flight firefighting plan in place for the accident aircraft, nor was such a plan required by regulation. Therefore, the aircraft crew did not have procedures or training directing them to aggressively attempt to locate and eliminate the source of the smoke, and to expedite their preparations for a possible emergency landing. In the absence of such a firefighting plan, they concentrated on preparing the aircraft for the diversion and landing.

10. There is no requirement that a fire-induced failure be considered when completing the system safety analysis required for certification. The fire-related failure of silicone elastomeric end caps installed on air conditioning ducts resulted in the addition of a continuous supply of conditioned air that contributed to the propagation and intensity of the fire.

11. The loss of primary flight displays and lack of outside visual references forced the pilots to be reliant on the standby instruments for at least some portion of the last minutes of the flight. In the deteriorating cockpit environment, the positioning and small size of these instruments would have made it difficult for the pilots to transition to their use, and to continue to maintain the proper spatial orientation of the aircraft.

3.2 Findings as to Risk

1. Although in many types of aircraft there are areas that are solely dependent on human intervention for fire detection and suppression, there is no requirement that the design of the aircraft provide for ready access to these areas. The lack of such access could delay the detection of a fire and significantly inhibit firefighting.

2. In the last minutes of the flight, the electronic navigation equipment and communications radios stopped operating, leaving the pilots with no accurate means of establishing their geographic position, navigating to the airport, and communicating with air traffic control.

3. Regulations do not require that aircraft be designed to allow for the immediate de-powering of all but the minimum essential electrical systems as part of an isolation process for the purpose of eliminating potential ignition sources.

4. Regulations do not require that checklists for isolating smoke or odours that could be related to an overheating condition be designed to be completed in a time frame that minimizes the possibility of an in-flight fire being ignited or sustained. As is the case with similar checklists in other aircraft, the applicable checklist for the MD-11 could take 20 to 30 minutes to complete. The time required to complete such checklists could allow anomalies, such as overheating components, to develop into ignition sources.

5. The Swissair Smoke/Fumes of Unknown Origin Checklist did not call for the cabin emergency lights to be turned on before the CABIN BUS switch was selected to the OFF position. Although a switch for these lights was available at the maître de cabine station, it is known that for a period of time the cabin crew were using flashlights while preparing for the landing, which potentially could have slowed their preparations.

6. Neither the Swissair nor Boeing Smoke/Fumes of Unknown Origin Checklist emphasized the need to immediately start preparations for a landing by including this consideration at the beginning of the checklist. Including this item at the end of the checklist de-emphasizes the importance of anticipating that any unknown smoke condition in an aircraft can worsen rapidly.

7. Examination of several MD-11 aircraft revealed various wiring discrepancies that had the potential to result in wire arcing. Other agencies have found similar discrepancies in other aircraft types. Such discrepancies reflect a shortfall within the aviation industry in wire installation, maintenance, and inspection procedures.

8. The consequence of contamination of an aircraft on its continuing airworthiness is not fully understood by the aviation industry. Various types of contamination may damage wire insulation, alter the flammability properties of materials, or provide fuel to spread a fire. The aviation industry has yet to quantify the impact of contamination on the continuing airworthiness and safe operation of an aircraft.

9. Heat damage and several arcing failure modes were found on in-service map lights. Although the fire in the occurrence aircraft did not start in the area of the map lights, their design and installation near combustible materials constituted a fire risk.

10. There is no guidance material to identify how to comply with the requirements of Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) 25.1353(b) in situations where physical/spatial wire separation is not practicable or workable, such as in confined areas.

11. The aluminum cap assembly used on the stainless steel oxygen line above the cockpit ceiling was susceptible to leaking or fracturing when exposed to the temperatures that were likely experienced by this cap assembly during the last few minutes of the flight. Such failures would exacerbate the fire and potentially affect crew oxygen supply. It could not be determined whether this occurred on the accident flight.

12. Inconsistencies with respect to CB reset practices have been recognized and addressed by major aircraft manufacturers and others in the aviation industry. Despite these initiatives, the regulatory environment, including regulations and advisory material, remains unchanged, creating the possibility that such “best practices” will erode or not be universally applied across the aviation industry.

13. The mandated cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recording time was insufficient to allow for the capture of additional, potentially useful, information.

14. The CVR and the flight data recorder (FDR) were powered from separate electrical buses; however, the buses received power from the same generator; this configuration was permitted by regulation. Both recorders stopped recording at almost the same time because of fire-related power interruptions; independent sources of aircraft power for the recorders may have allowed more information to be recorded.

15. Regulations did not require the CVR to have a source of electrical power independent from its aircraft electrical power supply. Therefore, when aircraft electrical power to the CVR was interrupted, potentially valuable information was not recorded.

16. Regulations and industry standards did not require quick access recorders (QAR) to be crash-protected, nor was there a requirement that QAR data also be recorded on the FDR. Therefore, potentially valuable information captured on the QAR was lost.

17. Regulations did not require the underwater locator beacon attachments on the CVR and the FDR to meet the same level of crash protection as other data recorder components.

18. The IFEN Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) project management structure did not ensure that the required elements were in place to design, install, and certify a system that included emergency electrical load-shedding procedures compatible with the MD-11 type certificate. No link was established between the manner in which the IFEN system was integrated with aircraft power and the initiation or propagation of the fire.

19. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) STC approval process for the IFEN did not ensure that the designated alteration station (DAS) employed personnel with sufficient aircraft-specific knowledge to appropriately assess the integration of the IFEN power supply with aircraft power before granting certification.

20. The FAA allowed a de facto delegation of a portion of their Aircraft Evaluation Group function to the DAS even though no provision existed within the FAA’s STC process to allow for such a delegation.

21. FAR 25.1309 requires that a system safety analysis be accomplished on every system installed in an aircraft; however, the requirements of FAR 25.1309 are not sufficiently stringent to ensure that all systems, regardless of their intended use, are integrated into the aircraft in a manner compliant with the aircraft’s type certificate.

22. Approach charts for the Halifax International Airport were kept in the ship’s library at the observer’s station and not within reach of the pilots. Retrieving these charts required both time and attention from the pilots during a period when they were faced with multiple tasks associated with operating the aircraft and planning for the landing.

23. While the SR Technics quality assurance (QA) program design was sound and met required standards, the training and implementation process did not sufficiently ensure that the program was consistently applied, so that potential safety aspects were always identified and mitigated.

24. The Swiss Federal Office for Civil Aviation audit procedures related to the SR Technics QA program did not ensure that the underlying factors that led to specific similar audit observations and discrepancies were addressed.

3.3 Other Findings

1. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police found no evidence to support the involvement of any explosive or incendiary device, or other criminal act in the initiation of the in-flight fire.

2. The 13-minute gap in very-high frequency communications was most likely the result of an incorrect frequency selection by the pilots.

3. The pilots made a timely decision to divert to the Halifax International Airport. Based on the limited cues available, they believed that although a diversion was necessary, the threat to the aircraft was not sufficient to warrant the declaration of an emergency or to initiate an emergency descent profile.

4. The flight crew were trained to dump fuel without restrictions and to land the aircraft in an overweight condition in an emergency situation, if required. 5. From any point along the Swissair Flight 111 flight path after the initial odour in the cockpit, the time required to complete an approach and landing to the Halifax International Airport would have exceeded the time available before the fire-related conditions in the aircraft cockpit would have precluded a safe landing.

6. Air conditioning anomalies have typically been viewed by regulators, manufacturers, operators, and pilots as not posing a significant and immediate threat to the safety of the aircraft that would require an immediate landing.

7. Actions by the flight crew in preparing the aircraft for landing, including their decisions to have the passenger cabin readied for landing and to dump fuel, were consistent with being unaware that an on-board fire was propagating.

8. Air traffic controllers were not trained on the general operating characteristics of aircraft during emergency or abnormal situations, such as fuel dumping.

9. Interactions between the pilots and the controllers did not affect the outcome of the occurrence.

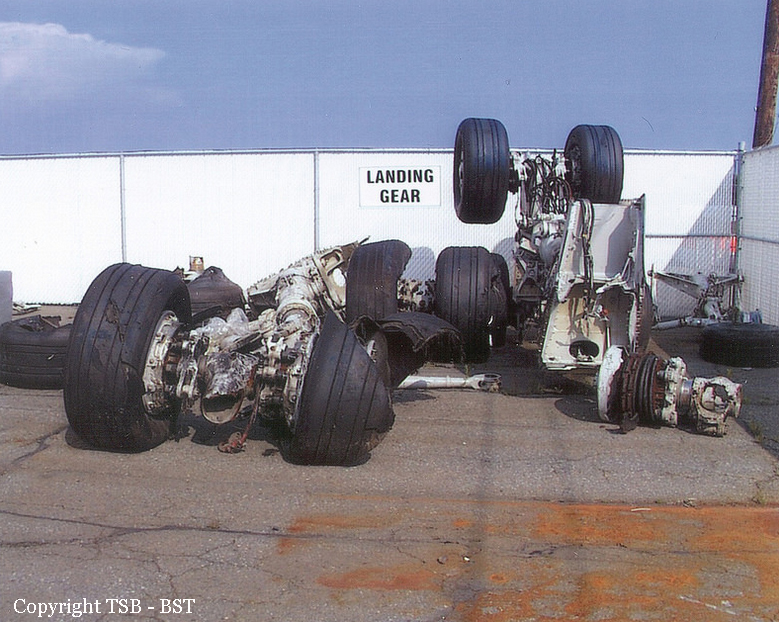

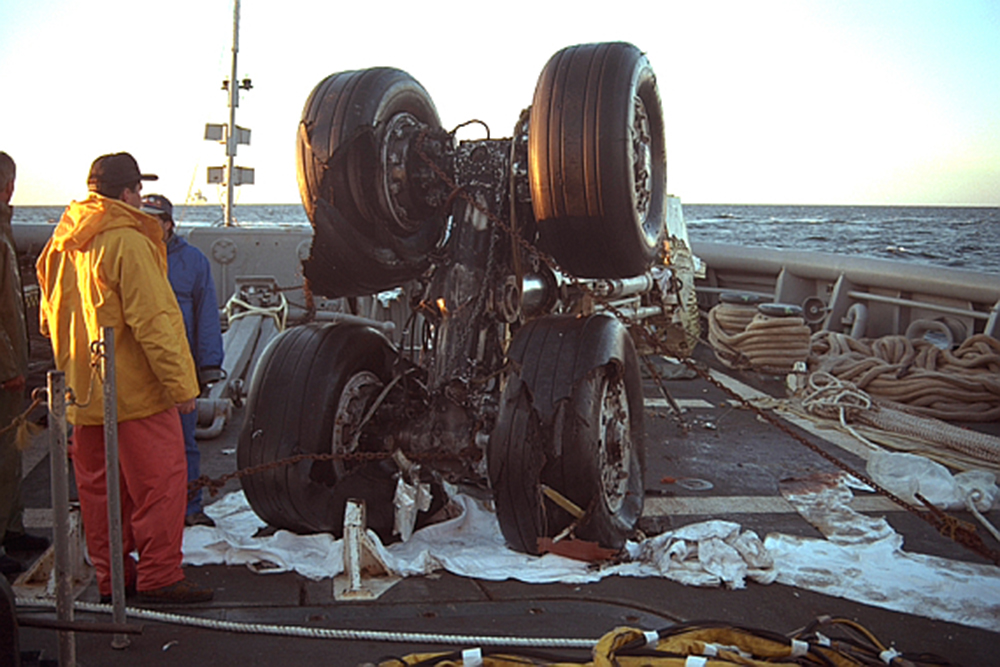

10. The first officer’s seat was occupied at the time of impact. It could not be determined whether the captain’s seat was occupied at the time of impact.

11. The pilots shut down Engine 2 during the final stages of the flight. No confirmed reason for the shutdown could be established; however, it is possible that the pilots were reacting to the illumination of the engine fire handle and FUEL switch emergency lights. There was fire damage in the vicinity of a wire that, if shorted to ground, would have illuminated these lights.

12. When the aircraft struck the water, the electrically driven standby attitude indicator gyro was still operating at a high speed; however, the instrument was no longer receiving electrical power. It is unknown whether the information displayed at the time of impact was indicative of the aircraft attitude.

13. Coordination between the pilots and the cabin crew was consistent with company procedures and training. Crew communications reflected that the situation was not being categorized as an emergency until about six minutes prior to the crash; however, soon after the descent to Halifax had started, rapid cabin preparations for an imminent landing were underway.

14. No smoke was reported in the cabin by the cabin crew at any time prior to CVR stoppage; however, it is likely that some smoke would have been present in the passenger cabin during the final few minutes of the flight. No significant heat damage or soot build-up was noted in the passenger seating areas, which is consistent with the fire being concentrated above the cabin ceiling.

15. No determination could be made about the occupancy of any of the individual passenger seats. Passenger oxygen masks were stowed at the time of impact, which is consistent with standard practice for an in-flight fire.

16. No technically feasible link was found between known electromagnetic interference/high-intensity radiated fields and any electrical discharge event leading to the ignition of the aircraft’s flammable materials.

17. Regulations did not require the recording of cockpit images, although it is technically feasible to do so in a crash-protected manner. Confirmation of information, such as flight instrument indications, switch position status, and aircraft system degradation, could not be completed without such information.

18. Portions of the CVR recording captured by the cockpit area microphone were difficult to decipher. When pilots use boom microphones, deciphering internal cockpit CVR communications becomes significantly easier; however, the use of boom microphones is not required by regulation for all phases of flight. Nor is it common practice for pilots to wear boom microphones at cruise altitude.

19. Indications of localized overheating were found on cabin ceiling material around overhead aisle and emergency light fixtures. It was determined that the overhead aisle and emergency light fixtures installed in the accident aircraft did not initiate the fire; however, their design created some heat-related material degradation that was mostly confined to the internal area of the fixtures adjacent to the bulbs.

20. At the time of this occurrence, there was no requirement within the aviation industry to record and report wiring discrepancies as a separate and distinct category to facilitate meaningful trend analysis in an effort to identify unsafe conditions associated with wiring anomalies.