Crash of a Cessna 208B Super Cargomaster in Helsinki

Date & Time:

Jan 31, 2005 at 1700 LT

Registration:

SE-KYH

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Helsinki-Örebro

MSN:

208B-0817

YOM:

2000

Flight number:

Helsinki – Örebro

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

3657.00

Aircraft flight hours:

6126

Circumstances:

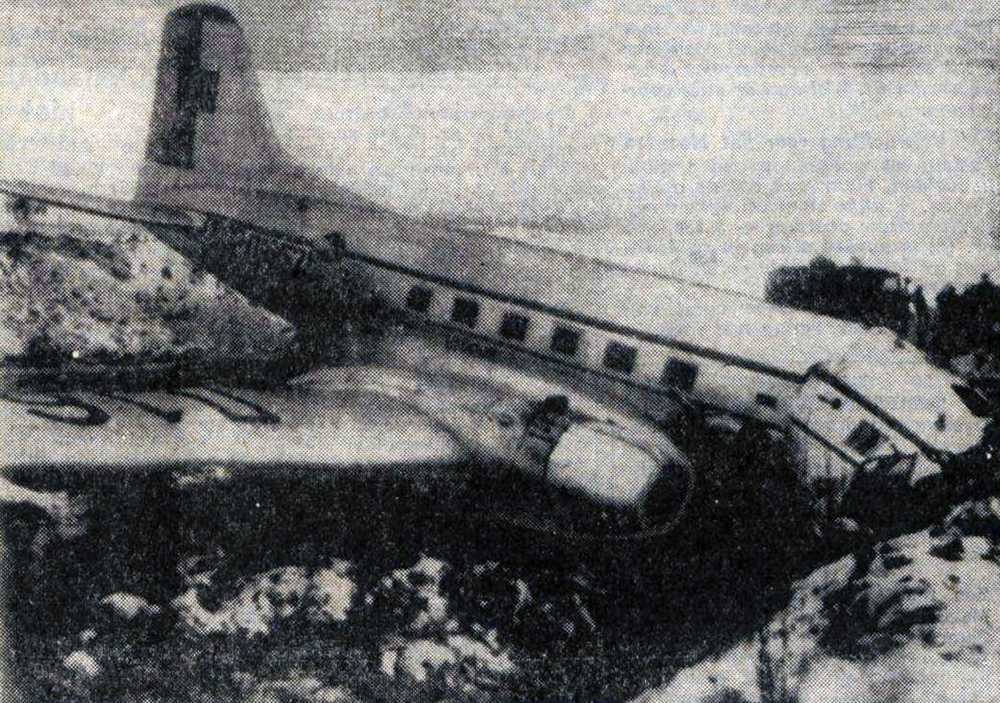

The aircraft landed at Helsinki–Vantaa airport at around 02:47 on Monday, 31.1.2005. After landing, the pilot taxied to apron number four in the southeastern corner of the aerodrome and unloaded the cargo from Sweden. After having done that he left the airport and went to a suite the company reserves for the crew to rest before the return leg to Sweden, which was planned for the following afternoon. The pilot has worked for the company for approximately five years. As per standard policy, the company operates the aircraft with a two person crew. On the day in question the co-pilot had taken ill and the pilot had flown alone. The return leg to Sweden was also planned as a one-person crew flight. The following morning the aircraft was refuelled with 420 l of Jet A-1, in accordance with the pilot’s instructions. All in all ca. 725 kg of fuel was reserved for the return leg. According to his account, the pilot checked in for duty at the airport at around 14:30. After arriving, the pilot began to brush the accumulated snow and frozen snow melt off the upper surfaces of the aircraft. He said that there was a great deal of snow and ice on the aircraft. The cargo that was to go to Sweden did not arrive in time for him to fly it to Skavsta, his primary destination. Therefore, he phoned in a change to the flight plan, choosing Örebro instead as his destination. Örebro was a better choice regarding follow-on transport of the freight. The pilot had outdated meteorological information for the return leg and the operational flight plan form was inadequately filed in. The flight plan was inadvertently filed for another tail number. Information which should be included such as date, crew, prevailing upper winds, estimates to different waypoints, fuel calculations and pilot signatures were omitted from the flight plan. The pilot had not left a copy of the operational flight plan for the ground crew. No weight and balance calculation for the flight was to be found in the cockpit. It had been left in the ground handling service’s briefing room but had been correctly calculated. The pilot did not have access to the latest aeronautical information for the return leg. Printouts of aeronautical information for the inbound leg were found in the cockpit of the wreckage. At 16:52:45 the pilot acknowledged on Helsinki Control Tower (TWR) frequency 118.600 MHz that he was taxiing to takeoff position RWY 22L at intersection Y. At 16:54:40 TWR gave him takeoff clearance from that intersection and gave him the wind direction. The pilot later said that he executed a normal takeoff, using 10 degrees of flaps. The aircraft lifted off at the normal speed of 80-90 KT. At 16:56:05 the pilot called TWR on 118.600 MHz saying “TOWER” just once. As per the pilot’s account everything went well until he reached the height of 800-1000 ft (250-300 m) at which point he retracted the trailing edge flaps. Immediately after flap retraction, the pilot lost control of the aircraft, which began turning to the right. The pilot attempted to fly the aircraft to the end section of runway 22R for an emergency landing. Shortly before crashing to the right side of the extension of runway 22L the pilot managed to get the wings level. He lost consciousness in the crash.

Probable cause:

The chain of events can be regarded as having begun when the aeroplane stood overnight on the tarmac, exposed to the weather. Snowfall accumulated on the upper surfaces of the fuselage, wings and stabilizers during the night forming a thick coat of ice and snow as it partly melted during the day and refroze when the ambient temperature dropped towards the evening. The pilot noticed the impurities when he performed a walkaround check. However, he did not order a de-icing. Instead, he tried to remove the ice with a brush. It is only possible to remove dry and loose snow by brushing. In this case the frozen water that had trickled down remained stuck to surfaces. The pilot executed a takeoff with an aircraft whose aerodynamic properties were fundamentally degraded due to impurities. During the initial climb, immediately after flap retraction, airflow separated from the surface of the wing and the pilot did not manage to regain control of the aircraft. The pilot did not recognize the stall for what is was and did not act in the required manner to recover or, then again, it could be that he had not received sufficient training for these kinds of situations. Several factors are considered to have affected the pilot’s actions. He was either ignorant or negligent as to the effect of impurities on the aeroplane’s aerodynamic properties. Furthermore, the pressure of keeping to the schedule during the early preflight briefing activities may have affected his decision, even though a change in the flight plan eliminated the actual rush. It is the impression of the investigation commission that these factors were the principal ones that contributed to the omission of proper deicing. A probable contributing factor, albeit one difficult to verify, could have been the financial aspect. The company may have considered buying deicing services from an external service provider as an additional expense. Investigations showed that the operator in question had ordered aeroplane de-icing at Helsinki–Vantaa airport only once during the previous and ongoing winter season. The company regularly flew to this airport. Processes were in place for pre-flight briefing as well as for freight forwarding. However, the flight schedules with reference to the opening times of the company’s primary destination airport did not allow for long delays in ground operations. This may have partly put pressure on the pilot to complete the other pre-flight activities as soon as possible. As for the flap setting, the pilot’s takeoff technique was not proper for the existing circumstances. Moreover, when the aeroplane stalled, the pilot did not execute any effective corrective action to regain control of the aircraft. These would have been, among other things: having reset the flaps to the position prior to the stall as well as having taken advantage of the engine power reserve. As per his account, the pilot did not utilize all available engine power. Instead, he stuck to the maximum value prescribed for normal operations as specified in the aircraft operations manual. The fact that the said flight was flown, contrary to normal operations with only a one person crew, can be considered a contributing factor.

Final Report: