Crash of a Swearingen SA227DC Metro 23 in Lockhart River: 15 killed

Date & Time:

May 7, 2005 at 1144 LT

Registration:

VH-TFU

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Bamaga – Lockhart River – Cairns

MSN:

DC-818B

YOM:

1992

Flight number:

HC675

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

13

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

15

Captain / Total hours on type:

3248.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

150

Aircraft flight hours:

26877

Aircraft flight cycles:

28529

Circumstances:

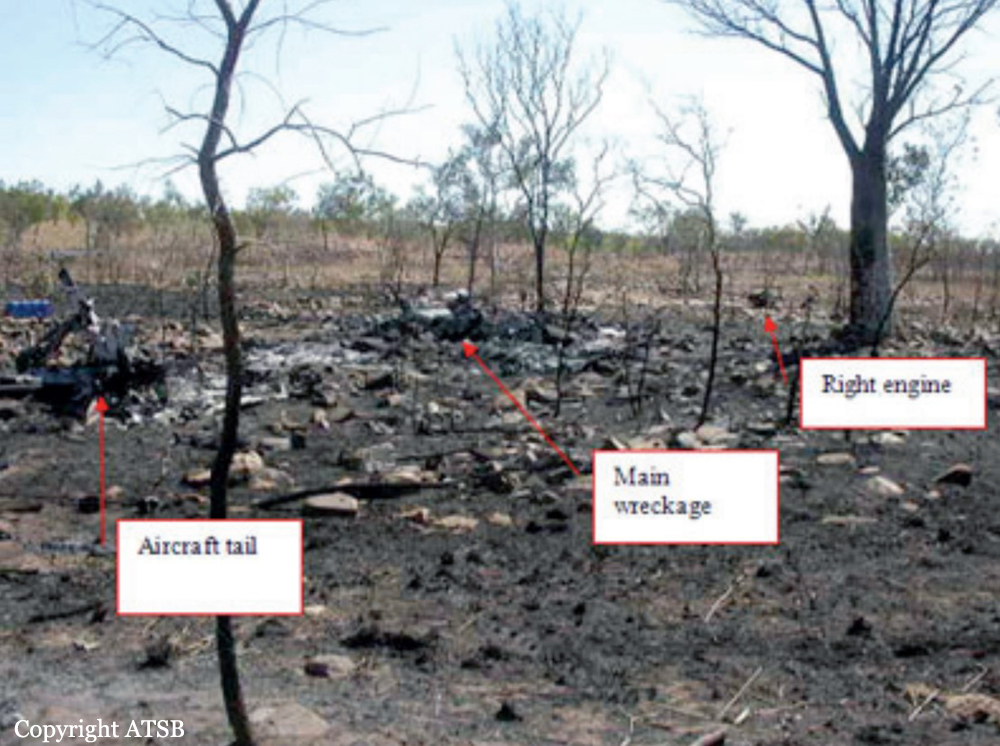

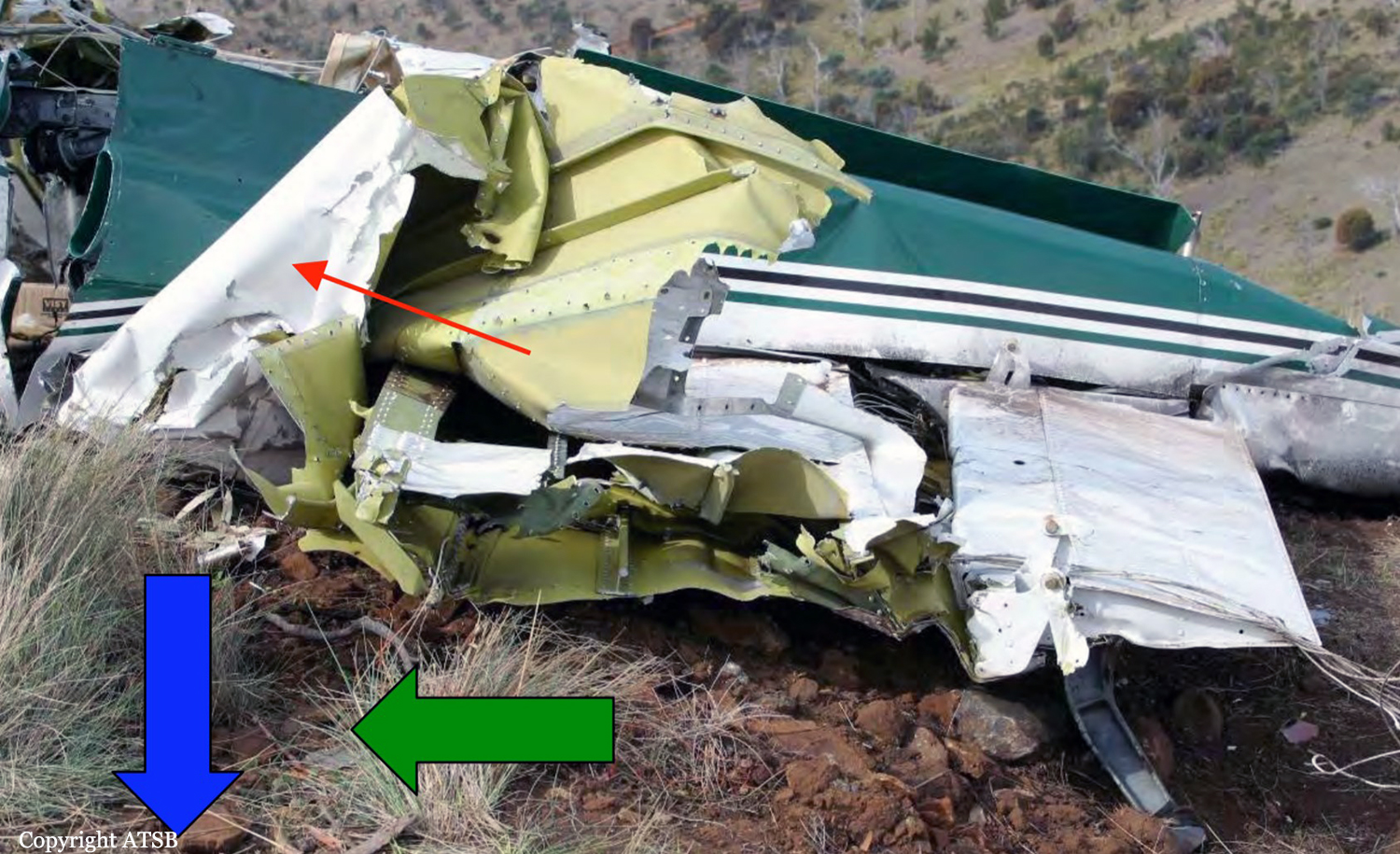

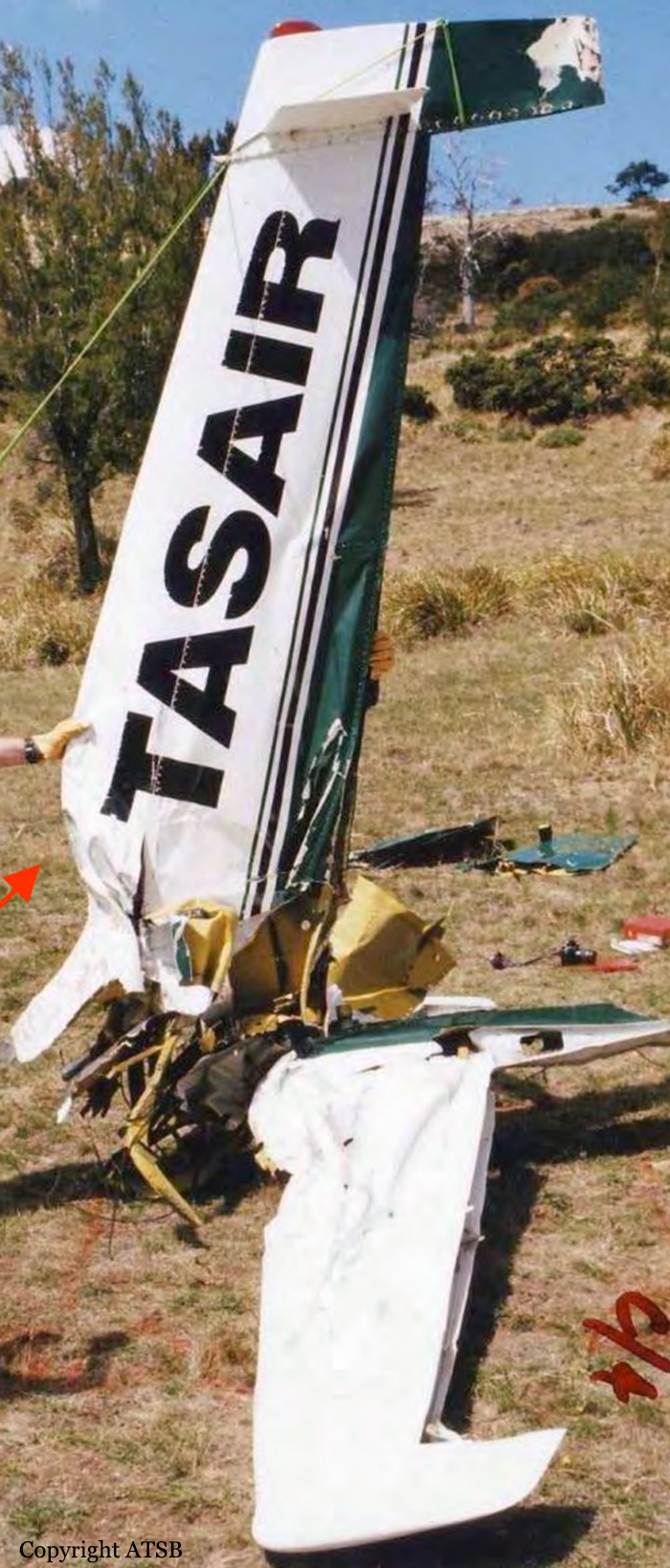

On 7 May 2005, a Fairchild Aircraft Inc. SA227DC Metro 23 aircraft, registered VH-TFU, with two pilots and 13 passengers, was being operated by Transair on an instrument flight rules (IFR) regular public transport (RPT) service from Bamaga to Cairns, with an intermediate stop at Lockhart River, Queensland. At 1143:39 Eastern Standard Time, the aircraft impacted terrain in the Iron Range National Park on the north-western slope of South Pap, a heavily timbered ridge, approximately 11 km north-west of the Lockhart River aerodrome. At the time of the accident, the crew was conducting an area navigation global navigation satellite system (RNAV (GNSS)) non-precision approach to runway 12. The aircraft was destroyed by the impact forces and an intense, fuel-fed, post-impact fire. There were no survivors. The accident was almost certainly the result of controlled flight into terrain; that is, an airworthy aircraft under the control of the flight crew was flown unintentionally into terrain, probably with no prior awareness by the crew of the aircraft’s proximity to terrain. Weather conditions in the Lockhart River area were poor and necessitated the conduct of an instrument approach procedure for an intended landing at the aerodrome. The cloud base was probably between 500 ft and 1,000 ft above mean sea level and the terrain to the west of the aerodrome, beneath the runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach, was probably obscured by cloud. The flight data recorder (FDR) data showed that, during the entire descent and approach, the aircraft engine and flight control system parameters were normal and that the crew were accurately navigating the aircraft along the instrument approach track. The FDR data and wreckage examination showed that the aircraft was configured for the approach, with the landing gear down and flaps extended to the half position. There were no radio broadcasts made by the crew on the air traffic services frequencies or the Lockhart River common traffic advisory frequency indicating that there was a problem with the aircraft or crew.

Probable cause:

Contributing factors relating to occurrence events and individual actions:

- The crew commenced the Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach, even though the crew were aware that the copilot did not have the appropriate endorsement and had limited experience to conduct this type of instrument approach.

- The descent speeds, approach speeds and rate of descent were greater than those specified for the aircraft in the Transair Operations Manual. The speeds and rate of descent also exceeded those appropriate for establishing a stabilised approach.

- During the approach, the aircraft descended below the segment minimum safe altitude for the aircraft's position on the approach.

- The aircraft's high rate of descent, and the descent below the segment minimum safe altitude, were not detected and/or corrected by the crew before the aircraft collided with terrain.

- The accident was almost certainly the result of controlled flight into terrain.

Contributing factors relating to local conditions:

- The crew probably experienced a very high workload during the approach.

- The crew probably lost situational awareness about the aircraft's position along the approach.

- The pilot in command had a previous history of conducting RNAV (GNSS) approaches with crew without appropriate endorsements, and operating the aircraft at speeds higher than those specified in the Transair Operations Manual.

- The Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach probably created higher pilot workload and reduced position situational awareness for the crew compared with most other instrument approaches. This was due to the lack of distance referencing to the missed approach point throughout the approach, and the longer than optimum final approach segment with three altitude limiting steps.

- The copilot had no formal training and limited experience to act effectively as a crew member during a Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach.

Contributing factors relating to Transair processes:

- Transair's flight crew training program had significant limitations, such as superficial or incomplete ground-based instruction during endorsement training, no formal training for new pilots in the operational use of GPS, no structured training on minimising the risk of controlled flight into terrain, and no structured training in crew resource management and operating effectively in a multi-crew environment. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's processes for supervising the standard of flight operations at the Cairns base had significant limitations, such as not using an independent approved check pilot to review operations, reliance on passive measures to detect problems, and no defined processes for selecting and monitoring the performance of the base manager. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's standard operating procedures for conducting instrument approaches had significant limitations, such as not providing clear guidance on approach speeds, not providing guidance for when to select aircraft configuration changes during an approach, no clear criteria for a stabilised approach, and no standardised phraseology for challenging safety-critical decisions and actions by other crew members. (Safety Issue)

- Transair had not installed a terrain awareness and warning system, such as an enhanced ground proximity warning system, in VH-TFU.

- Transair's organisational structure, and the limited responsibilities given to non-management personnel, resulted in high work demands on the chief pilot. It also resulted in a lack of independent evaluation of training and checking, and created disincentives and restricted opportunities within Transair to report safety concerns with management decision making. (Safety Issue)

- Transair did not have a structured process for proactively managing safety related risks associated with its flight operations. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's chief pilot did not demonstrate a high level of commitment to safety. (Safety Issue)

Contributing factors relating to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority processes:

- CASA did not provide sufficient guidance to its inspectors to enable them to effectively and consistently evaluate several key aspects of operator management systems. These aspects included evaluating organisational structure and staff resources, evaluating the suitability of key personnel, evaluating organisational change, and evaluating risk management processes. (Safety Issue)

- CASA did not require operators to conduct structured and/or comprehensive risk assessments, or conduct such assessments itself, when evaluating applications for the initial issue or subsequent variation of an Air Operator's Certificate. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to local conditions:

- There was a significant potential for crew resource management problems within the crew in high workload situations, given that there was a high trans-cockpit authority gradient and neither pilot had previously demonstrated a high level of crew resource management skills.

- The pilots' endorsements, clearance to line operations, and route checks did not meet all the relevant regulatory and operations manual requirements to conduct RPT flights on the Metro aircraft.

- Some cockpit displays and annunciators relevant to conducting an instrument approach were in a sub-optimal position in VH-TFU for useability or attracting the attention of both pilots.

Other factors relating to instruments approaches:

- Based on the available evidence, the Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach design resulted in mode 2A ground proximity warning system alerts and warnings when flown on the recommended profile or at the segment minimum safe altitudes. (Safety Issue)

- The Australian convention for waypoint names in RNAV (GNSS) approaches did not maximise the ability to discriminate between waypoint names on the aircraft global positioning system display and/or on the approach chart. (Safety Issue)

- There were several design aspects of the Jeppesen RNAV (GNSS) approach charts that could lead to pilot confusion or reduction in situational awareness. These included limited reference regarding the 'distance to run' to the missed approach point, mismatches in the vertical alignment of the plan-view and profile-view on charts such as that for the Lockhart River runway 12 approach, use of the same font size and type for waypoint names and 'NM' [nautical miles], and not depicting the offset in degrees between the final approach track and the runway centreline. (Safety Issue)

- Jeppesen instrument approach charts depicted coloured contours on the plan-view of approach charts based on the maximum height of terrain relative to the airfield only, rather than also considering terrain that increases the final approach or missed approach procedure gradient to be steeper than the optimum. Jeppesen instrument approach charts did not depict the terrain profile on the profile-view although the segment minimum safe altitudes were depicted. (Safety Issue)

- Airservices Australia's instrument approach charts did not depict the terrain contours on the plan-view. They also did not depict the terrain profile on the profile-view, although the segment minimum safe altitudes were depicted. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to Transair processes:

- Transair's flight crew proficiency checking program had significant limitations, such as the frequency of proficiency checks and the lack of appropriate approvals of many of the pilots conducting proficiency checks. (Safety Issue)

- The Transair Operations Manual was distributed to company pilots in a difficult to use electronic format, resulting in pilots minimising use of the manual. (Safety Issue) Other factors relating to regulatory requirements and guidance

- Although CASA released a discussion paper in 2000, and further development had occurred since then, there was no regulatory requirement for initial or recurrent crew resource management training for RPT operators. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for flight crew undergoing a type rating on a multi-crew aircraft to be trained in procedures for crew incapacitation and crew coordination, including allocation of pilot tasks, crew cooperation and use of checklists. This was required by ICAO Annex 1 to which Australia had notified a difference. (Safety Issue)

- The regulatory requirements concerning crew qualifications during the conduct of instrument approaches in a multi-crew RPT operation was potentially ambiguous as to whether all crew members were required to be qualified to conduct the type of approach being carried out. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's guidance material provided to operators about the structure and content of an operations manual was not as comprehensive as that provided by ICAO in areas such as multi-crew procedures and stabilised approach criteria. (Safety Issue)

- Although CASA released a discussion paper in 2000, and further development and publicity had occurred since then, there was no regulatory requirement for RPT operators to have a safety management system. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for instrument approach charts to include coloured contours to depict terrain. This was required by a standard in ICAO Annex 4 in certain situations. Australia had not notified a difference to the standard. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for multi-crew RPT aircraft to be fitted with a serviceable autopilot. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to Civil Aviation Safety Authority processes:

- CASA's oversight of Transair, in relation to the approval of Air Operator's Certificate variations and the conduct of surveillance, was sometimes inconsistent with CASA's policies, procedures and guidelines.

- CASA did not have a systematic process for determining the relative risk levels of airline operators. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's process for evaluating an operations manual did not consider the useability of the manual, particularly manuals in electronic format. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's process for accepting an instrument approach did not involve a systematic risk assessment of pilot workload and other potential hazards, including activation of a ground proximity warning system. (Safety Issue) Other key findings An 'other key finding' is defined as any finding, other than that associated with safety factors, considered important to include in an investigation report. Such findings may resolve ambiguity or controversy, describe possible scenarios or safety factors when firm safety factor findings were not able to be made, or note events or conditions which 'saved the day' or played an important role in reducing the risk associated with an occurrence.

- It was very likely that both crew members were using RNAV (GNSS) approach charts produced by Jeppesen.

- The cockpit voice recorder did not function as intended due to an internal fault that had developed sometime before the accident flight and that was not discovered or diagnosed by flight crew or maintenance personnel.

- There was no evidence to indicate that the GPWS did not function as designed.

- There would have been insufficient time for the crew to effectively respond to the GPWS alert and warnings that were probably annunciated during the final 5 seconds prior to impact with terrain.

- The crew commenced the Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach, even though the crew were aware that the copilot did not have the appropriate endorsement and had limited experience to conduct this type of instrument approach.

- The descent speeds, approach speeds and rate of descent were greater than those specified for the aircraft in the Transair Operations Manual. The speeds and rate of descent also exceeded those appropriate for establishing a stabilised approach.

- During the approach, the aircraft descended below the segment minimum safe altitude for the aircraft's position on the approach.

- The aircraft's high rate of descent, and the descent below the segment minimum safe altitude, were not detected and/or corrected by the crew before the aircraft collided with terrain.

- The accident was almost certainly the result of controlled flight into terrain.

Contributing factors relating to local conditions:

- The crew probably experienced a very high workload during the approach.

- The crew probably lost situational awareness about the aircraft's position along the approach.

- The pilot in command had a previous history of conducting RNAV (GNSS) approaches with crew without appropriate endorsements, and operating the aircraft at speeds higher than those specified in the Transair Operations Manual.

- The Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach probably created higher pilot workload and reduced position situational awareness for the crew compared with most other instrument approaches. This was due to the lack of distance referencing to the missed approach point throughout the approach, and the longer than optimum final approach segment with three altitude limiting steps.

- The copilot had no formal training and limited experience to act effectively as a crew member during a Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach.

Contributing factors relating to Transair processes:

- Transair's flight crew training program had significant limitations, such as superficial or incomplete ground-based instruction during endorsement training, no formal training for new pilots in the operational use of GPS, no structured training on minimising the risk of controlled flight into terrain, and no structured training in crew resource management and operating effectively in a multi-crew environment. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's processes for supervising the standard of flight operations at the Cairns base had significant limitations, such as not using an independent approved check pilot to review operations, reliance on passive measures to detect problems, and no defined processes for selecting and monitoring the performance of the base manager. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's standard operating procedures for conducting instrument approaches had significant limitations, such as not providing clear guidance on approach speeds, not providing guidance for when to select aircraft configuration changes during an approach, no clear criteria for a stabilised approach, and no standardised phraseology for challenging safety-critical decisions and actions by other crew members. (Safety Issue)

- Transair had not installed a terrain awareness and warning system, such as an enhanced ground proximity warning system, in VH-TFU.

- Transair's organisational structure, and the limited responsibilities given to non-management personnel, resulted in high work demands on the chief pilot. It also resulted in a lack of independent evaluation of training and checking, and created disincentives and restricted opportunities within Transair to report safety concerns with management decision making. (Safety Issue)

- Transair did not have a structured process for proactively managing safety related risks associated with its flight operations. (Safety Issue)

- Transair's chief pilot did not demonstrate a high level of commitment to safety. (Safety Issue)

Contributing factors relating to the Civil Aviation Safety Authority processes:

- CASA did not provide sufficient guidance to its inspectors to enable them to effectively and consistently evaluate several key aspects of operator management systems. These aspects included evaluating organisational structure and staff resources, evaluating the suitability of key personnel, evaluating organisational change, and evaluating risk management processes. (Safety Issue)

- CASA did not require operators to conduct structured and/or comprehensive risk assessments, or conduct such assessments itself, when evaluating applications for the initial issue or subsequent variation of an Air Operator's Certificate. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to local conditions:

- There was a significant potential for crew resource management problems within the crew in high workload situations, given that there was a high trans-cockpit authority gradient and neither pilot had previously demonstrated a high level of crew resource management skills.

- The pilots' endorsements, clearance to line operations, and route checks did not meet all the relevant regulatory and operations manual requirements to conduct RPT flights on the Metro aircraft.

- Some cockpit displays and annunciators relevant to conducting an instrument approach were in a sub-optimal position in VH-TFU for useability or attracting the attention of both pilots.

Other factors relating to instruments approaches:

- Based on the available evidence, the Lockhart River Runway 12 RNAV (GNSS) approach design resulted in mode 2A ground proximity warning system alerts and warnings when flown on the recommended profile or at the segment minimum safe altitudes. (Safety Issue)

- The Australian convention for waypoint names in RNAV (GNSS) approaches did not maximise the ability to discriminate between waypoint names on the aircraft global positioning system display and/or on the approach chart. (Safety Issue)

- There were several design aspects of the Jeppesen RNAV (GNSS) approach charts that could lead to pilot confusion or reduction in situational awareness. These included limited reference regarding the 'distance to run' to the missed approach point, mismatches in the vertical alignment of the plan-view and profile-view on charts such as that for the Lockhart River runway 12 approach, use of the same font size and type for waypoint names and 'NM' [nautical miles], and not depicting the offset in degrees between the final approach track and the runway centreline. (Safety Issue)

- Jeppesen instrument approach charts depicted coloured contours on the plan-view of approach charts based on the maximum height of terrain relative to the airfield only, rather than also considering terrain that increases the final approach or missed approach procedure gradient to be steeper than the optimum. Jeppesen instrument approach charts did not depict the terrain profile on the profile-view although the segment minimum safe altitudes were depicted. (Safety Issue)

- Airservices Australia's instrument approach charts did not depict the terrain contours on the plan-view. They also did not depict the terrain profile on the profile-view, although the segment minimum safe altitudes were depicted. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to Transair processes:

- Transair's flight crew proficiency checking program had significant limitations, such as the frequency of proficiency checks and the lack of appropriate approvals of many of the pilots conducting proficiency checks. (Safety Issue)

- The Transair Operations Manual was distributed to company pilots in a difficult to use electronic format, resulting in pilots minimising use of the manual. (Safety Issue) Other factors relating to regulatory requirements and guidance

- Although CASA released a discussion paper in 2000, and further development had occurred since then, there was no regulatory requirement for initial or recurrent crew resource management training for RPT operators. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for flight crew undergoing a type rating on a multi-crew aircraft to be trained in procedures for crew incapacitation and crew coordination, including allocation of pilot tasks, crew cooperation and use of checklists. This was required by ICAO Annex 1 to which Australia had notified a difference. (Safety Issue)

- The regulatory requirements concerning crew qualifications during the conduct of instrument approaches in a multi-crew RPT operation was potentially ambiguous as to whether all crew members were required to be qualified to conduct the type of approach being carried out. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's guidance material provided to operators about the structure and content of an operations manual was not as comprehensive as that provided by ICAO in areas such as multi-crew procedures and stabilised approach criteria. (Safety Issue)

- Although CASA released a discussion paper in 2000, and further development and publicity had occurred since then, there was no regulatory requirement for RPT operators to have a safety management system. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for instrument approach charts to include coloured contours to depict terrain. This was required by a standard in ICAO Annex 4 in certain situations. Australia had not notified a difference to the standard. (Safety Issue)

- There was no regulatory requirement for multi-crew RPT aircraft to be fitted with a serviceable autopilot. (Safety Issue)

Other factors relating to Civil Aviation Safety Authority processes:

- CASA's oversight of Transair, in relation to the approval of Air Operator's Certificate variations and the conduct of surveillance, was sometimes inconsistent with CASA's policies, procedures and guidelines.

- CASA did not have a systematic process for determining the relative risk levels of airline operators. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's process for evaluating an operations manual did not consider the useability of the manual, particularly manuals in electronic format. (Safety Issue)

- CASA's process for accepting an instrument approach did not involve a systematic risk assessment of pilot workload and other potential hazards, including activation of a ground proximity warning system. (Safety Issue) Other key findings An 'other key finding' is defined as any finding, other than that associated with safety factors, considered important to include in an investigation report. Such findings may resolve ambiguity or controversy, describe possible scenarios or safety factors when firm safety factor findings were not able to be made, or note events or conditions which 'saved the day' or played an important role in reducing the risk associated with an occurrence.

- It was very likely that both crew members were using RNAV (GNSS) approach charts produced by Jeppesen.

- The cockpit voice recorder did not function as intended due to an internal fault that had developed sometime before the accident flight and that was not discovered or diagnosed by flight crew or maintenance personnel.

- There was no evidence to indicate that the GPWS did not function as designed.

- There would have been insufficient time for the crew to effectively respond to the GPWS alert and warnings that were probably annunciated during the final 5 seconds prior to impact with terrain.

Final Report: