Circumstances:

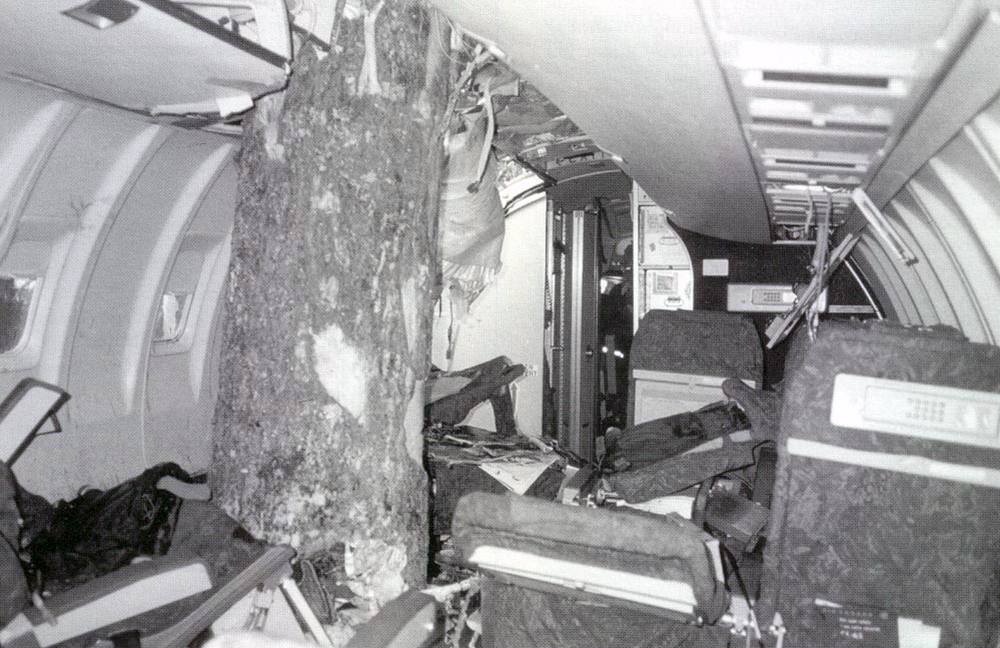

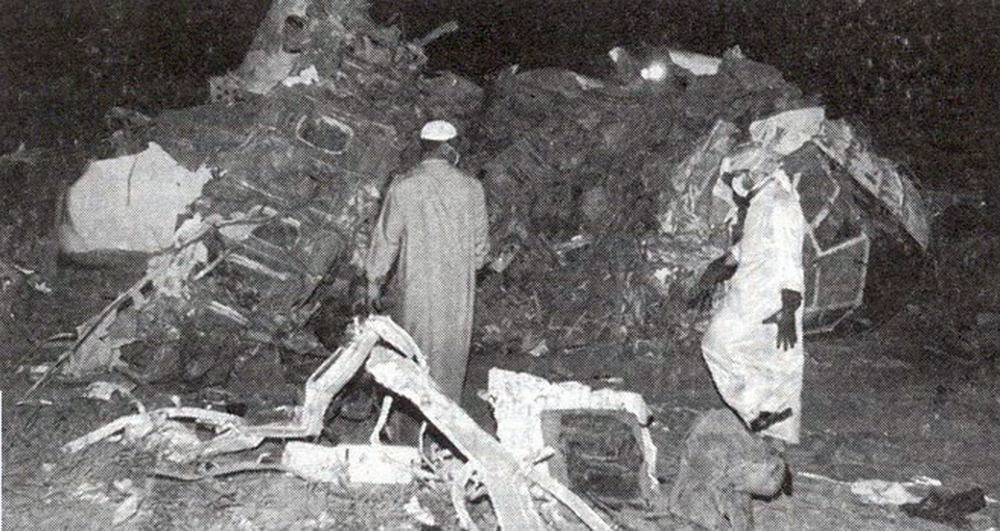

Air Canada Flight 646, C-FSKI, departed Toronto-Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario, at 2124 eastern standard time on a scheduled flight to Fredericton, New Brunswick. On arrival, the reported ceiling was 100 feet obscured, the visibility one-eighth of a mile in fog, and the runway visual range 1200 feet. The crew conducted a Category I instrument landing system approach to runway 15 and elected to land. On reaching about 35 feet, the captain assessed that the aircraft was not in a position to land safely and ordered the first officer, who was flying the aircraft, to go around. As the aircraft reached its go-around pitch attitude of about 10 degrees, the aircraft stalled aerodynamically, struck the runway, veered to the right and then travelled—at full power and uncontrolled—about 2100 feet from the first impact point, struck a large tree and came to rest. An evacuation was conducted; however, seven passengers were trapped in the aircraft until rescued. Of the 39 passengers and 3 crew members, 9 were seriously injured and the rest received minor or no injuries. The accident occurred at 2348 Atlantic standard time.

Probable cause:

Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors:

1. Although for the time of the approach the weather reported for Fredericton—ceiling 100 feet and visibility c mile—was below the 200-foot decision height and the charted ½ -mile (RVR 2600) visibility for the landing, the approach was permitted because the reported RVR of 1200 feet was at the minimum RVR specified in CAR 602.129.

2. Based on the weather and visibility, runway length, approach and runway lighting, runway condition, and the first officer’s flying experience, allowing the first officer to fly the approach is questionable.

3. The first officer allowed the aircraft to deviate from the flight path to the extent that a go-around was required, which is an indication of his ability to transition to landing in the existing environmental conditions.

4. Disengagement of the autopilot at 165 feet rather than at the 80-foot minimum autopilot altitude resulted in an increased workload for the PF, allowed deviations

from the glide path, and deprived the pilots of better visual cues for landing.

5. In the occurrence environmental conditions, the lack of runway centre line and touchdown-zone lighting probably contributed to the first officer not being able to see the runway environment clearly enough to enable him to maintain the aircraft on the visual glide path and runway centre line.

6. The first officer’s inexperience and lack of training in flying the CL-65 in low-visibility conditions contributed to his inability to successfully complete the landing.

7. The situation of a captain being the PNF when ordering a go-around probably played a part in the uncertainty regarding the thrust lever advance and the raising of the flaps because there was no documented procedure covering their duties.

8. The go-around was attempted from a low-energy situation outside of the flight boundaries certified for the published go-around procedures; the aircraft’s low energy was primarily the result of the power being at idle.

9. The sequential nature of steps within the go-around procedures, in particular, in directing the pitch adjustment prior to noting the airspeed, the compelling nature of the command bars, and the high level of concentration required when initiating the go-around contributed to the first officer’s inadequate monitoring of the airspeed during the go-around attempt.

10. Following the command bars in go-around mode does not ensure that a safe flying speed is maintained, because the positioning of the command bars does not take into consideration the airspeed, flap configuration, and the rate of change of the angle of attack, considerations required to compute stall margin.

11. The conditions under which the go-arounds are demonstrated for aircraft certification do not form part of the documentation that leads to aircraft limitations or boundaries for the go-around procedure; this contributed to these factors not being taken into account when the go-around procedures were incorporated in aircraft and training manuals.

12. The published go-around procedure does not adequately reflect that once power is reduced to idle for landing, a go-around will probably not be completed without the aircraft contacting the runway (primarily because of the time required for the engines to spool up to go-around thrust).

13. The Air Canada stall recovery training, as approved by Transport Canada, did not prepare the crew for the conditions in which the occurrence aircraft stick shaker activated and the aircraft stalled.

14. The limitations of the ice-detection and annunciation systems and the procedures on the use of wing anti-ice did not ensure that the wing would remain ice-free during flight.

15. Ice accretion studies indicate that the aircraft was in an icing environment for at least 60 seconds prior to the stall, and that during this period a thin layer of mixed ice with some degree of roughness probably accumulated on the leading edges of the wings. Any ice on the wings would have reduced the safety margins of the stall protection system.

16. The implications of ice build-up below the threshold of detection, and the inhibiting of the ice advisory below 400 feet, were not adequately considered when the stall margin was being determined during the 1996 certification of the ice-detection system and associated procedures.

17. The stall protection system operated as designed: that it did not prevent the stall is related to the degraded performance of the wings.

18. The Category I approach was without the extra aids and defences required for Category II approaches.

19. Canadian regulations with respect to Category I approaches are more liberal than those of most countries and are not consistent with the ICAO International Standards and Recommended Practices (Annex 14), which defines visibility limits; in Canada, the visibility values, other than RVR, are advisory only.

20. Even though a Category I approach may be conducted in weather conditions reported to be lower than the landing minima specified for the approach, there is no special training required for any flight crew member, and there is no requirement that flight crew be tested on their ability to fly in such conditions.

21. Air Canada’s procedures required that the captain fly the aircraft when conducting a Category II approach, in all weather conditions; however, the decision as to who will fly low-visibility Category I approaches was left to the captain, who may not be in a position to adequately assess the first officer’s ability to conduct the approach.

22. The aircraft stalled at an angle of attack approximately 4.5 degrees lower, and at a CLmax 0.26 lower, than would be expected for the natural stall.

23. On final approach below 1000 feet agl, the wing performance on the accident flight was degraded over the wing performance at the same phase on the previous flight.

24. The engineering simulator comparison indicated two step reductions in aircraft performance, at 400 feet and 150 feet agl, as a result of local flow separation in the vicinity of wing station (WS) 247 and WS 253.

25. Pitting on the leading edges of the wings had a negligible effect on the performance of the aircraft.

26. The sealant on the leading edges of both wings was missing in some places and protruding from the surface 2 to 3 mm in others. Test flights indicate that the effect of the protruding chordwise sealant on the aircraft performance could have accounted for a reduction of 1.7 to 2.0 degrees in maximum fuselage angle of attack and of 0.03 to 0.05 in CLmax.

27. The maximum reduction in angle of attack resulting from ground effect is considered to be in the order of 0.75±0.5 degree: the aircraft angle of attack was influenced by ground effect during the go-around manoeuvre.

28. The performance loss caused by the protruding sealant and by ground effect was not great enough to account for the performance loss experienced; there is no apparent phenomenon other than ice accretion that could account for the remainder of the performance loss.

29. Neither Bombardier Inc., nor Transport Canada, nor Air Canada ensured that the regulations, manuals, and training programs prepared flight crews to successfully and consistently transition to visual flight for a landing or to go-around in the conditions that existed during this flight, especially considering the energy state of the aircraft when the go-around was commenced.

Other Findings:

1. Both the captain and the first officer were licensed and qualified for the duties performed during the flight in accordance with regulations and Air Canada training

and standards, except for minor training deficiencies with regard to emergency equipment.

2. The occurrence flight attendant was trained and qualified for the flight in accordance with existing requirements.

3. The aircraft was within its weight and centre-of-gravity limits for the entire flight.

4. Records indicate that the aircraft was certified, equipped, and maintained in accordance with existing regulations and approved procedures.

5. There was no indication found of a failure or malfunction of any aircraft component prior to or during the flight.

6. When the stick shaker activated, it is unlikely that the crew could have landed the aircraft safely or completed a go-around without ground contact.

7. When power was selected for the go-around, the engines accelerated at a rate that would have been expected had the thrust levers been slammed to the go-around power setting.

8. The aircraft was not equipped with an emergency locator transmitter, nor was one required by regulation.

9. The lack of an emergency locator transmitter probably delayed locating the aircraft and its occupants.

10. Passengers and crew had no effective means of signaling emergency rescue services personnel.

11. The flight crew did not receive practical training on the operation of any emergency exits during their initial training program, even though this was required by

regulation.

12. Air Canada’s initial training program for flight crew did not include practical training in the operation of over-wing exits or the flight deck escape hatch.

13. Air Canada’s annual emergency procedures training for flight crew regarding the operation and use of emergency exits did not include practical training every third year, as required. Annual emergency exit training was done by demonstration only.

14. The flight crew were unaware that a pry bar was standard emergency equipment on the aircraft.

15. The four emergency flashlights carried on board were located in the same general area of the aircraft, increasing the possibility that all could be rendered inaccessible or unserviceable in an accident. (See section 4.1.6)

16. That there was a Flight Service Station specialist, as opposed to a tower controller, at the Fredericton airport at the time of the arrival of ACA 646 was not material to this occurrence.