Circumstances:

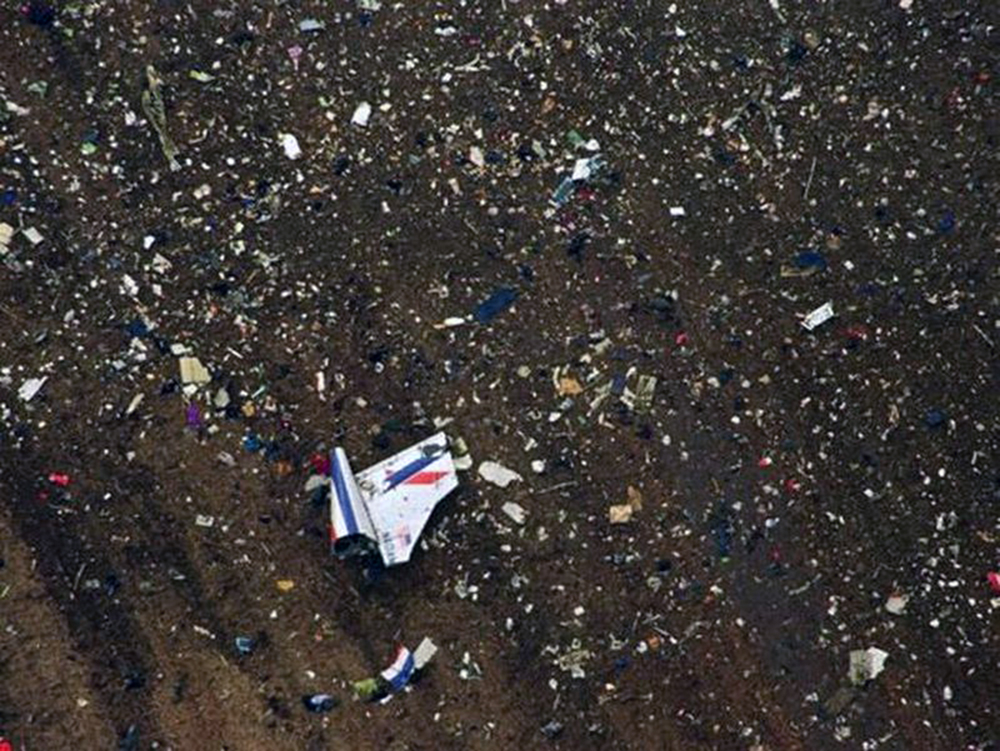

American Eagle Flight 4184 was scheduled to depart the gate in Indianapolis at 14:10; however, due to a change in the traffic flow because of deteriorating weather conditions at destination Chicago-O'Hare, the flight left the gate at 14:14 and was held on the ground for 42 minutes before receiving an IFR clearance to O'Hare. At 14:55, the controller cleared flight 4184 for takeoff. The aircraft climbed to an enroute altitude of 16,300 feet. At 15:13, flight 4184 began the descent to 10,000 feet. During the descent, the FDR recorded the activation of the Level III airframe de-icing system. At 15:18, shortly after flight 4184 leveled off at 10,000 feet, the crew received a clearance to enter a holding pattern near the LUCIT intersection and they were told to expect further clearance at 15:45, which was revised to 16:00 at 15:38. Three minutes later the Level III airframe de-icing system activated again. At 15:56, the controller contacted flight 4184 and instructed the flight crew to descend to 8,000 feet. The engine power was reduced to the flight idle position, the propeller speed was 86 percent, and the autopilot remained engaged in the vertical speed (VS) and heading select (HDG SEL) modes. At 15:57:21, as the airplane was descending in a 15-degree right-wing-down attitude at 186 KIAS, the sound of the flap overspeed warning was recorded on the CVR. The crew selected flaps from 15 to zero degrees and the AOA and pitch attitude began to increase. At 15:57:33, as the airplane was descending through 9,130 feet, the AOA increased through 5 degrees, and the ailerons began deflecting to a right-wing-down position. About 1/2 second later, the ailerons rapidly deflected to 13:43 degrees right-wing-down, the autopilot disconnected. The airplane rolled rapidly to the right, and the pitch attitude and AOA began to decrease. Within several seconds of the initial aileron and roll excursion, the AOA decreased through 3.5 degrees, the ailerons moved to a nearly neutral position, and the airplane stopped rolling at 77 degrees right-wing-down. The airplane then began to roll to the left toward a wings-level attitude, the elevator began moving in a nose-up direction, the AOA began increasing, and the pitch attitude stopped at approximately 15 degrees nose down. At 15:57:38, as the airplane rolled back to the left through 59 degrees right-wing-down (towards wings level), the AOA increased again through 5 degrees and the ailerons again deflected rapidly to a right-wing-down position. The captain's nose-up control column force exceeded 22 pounds, and the airplane rolled rapidly to the right, at a rate in excess of 50 degrees per second. The captain's nose-up control column force decreased below 22 pounds as the airplane rolled through 120 degrees, and the first officer's nose-up control column force exceeded 22 pounds just after the airplane rolled through the inverted position (180 degrees). Nose-up elevator inputs were indicated on the FDR throughout the roll, and the AOA increased when nose-up elevator increased. At 15:57:45 the airplane rolled through the wings-level attitude (completion of first full roll). The nose-up elevator and AOA then decreased rapidly, the ailerons immediately deflected to 6 degrees left-wing-down and then stabilized at about 1 degree right-wing-down, and the airplane stopped rolling at 144 degrees right wing down. At 15:57:48, as the airplane began rolling left, back towards wings level, the airspeed increased through 260 knots, the pitch attitude decreased through 60 degrees nose down, normal acceleration fluctuated between 2.0 and 2.5 G, and the altitude decreased through 6,000 feet. At 15:57:51, as the roll attitude passed through 90 degrees, continuing towards wings level, the captain applied more than 22 pounds of nose-up control column force, the elevator position increased to about 3 degrees nose up, pitch attitude stopped decreasing at 73 degrees nose down, the airspeed increased through 300 KIAS, normal acceleration remained above 2 G, and the altitude decreased through 4,900 feet. At 15:57:53, as the captain's nose-up control column force decreased below 22 pounds, the first officer's nose-up control column force again exceeded 22 pounds and the captain made the statement "nice and easy." At 15:57:55, the normal acceleration increased to over 3.0 G. Approximately 1.7 seconds later, as the altitude decreased through 1,700 feet, the elevator position and vertical acceleration began to increase rapidly. The last recorded data on the FDR occurred at an altitude of 1,682 feet (vertical speed of approximately 500 feet per second), and indicated that the airplane was at an airspeed of 375 KIAS, a pitch attitude of 38 degrees nose down with 5 degrees of nose-up elevator, and was experiencing a vertical acceleration of 3.6 G. The airplane impacted a wet soybean field partially inverted, in a nose down, left-wing-low attitude. Based on petitions filed for reconsideration of the probable cause, the NTSB on September 2002 updated it's findings.

Probable cause:

The loss of control, attributed to a sudden and unexpected aileron hinge moment reversal, that occurred after a ridge of ice accreted beyond the deice boots while the airplane was in a holding pattern during which it intermittently encountered supercooled cloud and drizzle/rain drops, the size and water content of which exceeded those described in the icing certification envelope. The airplane was susceptible to this loss of control, and the crew was unable to recover. Contributing to the accident were:

1) the French Directorate General for Civil Aviation’s (DGAC’s) inadequate oversight of the ATR 42 and 72, and its failure to take the necessary corrective action to ensure continued airworthiness in icing conditions;

2) the DGAC’s failure to provide the FAA with timely airworthiness information developed from previous ATR incidents and accidents in icing conditions,

3) the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) failure to ensure that aircraft icing certification requirements, operational requirements for flight into icing conditions, and FAA published aircraft icing information adequately accounted for the hazards that can result from flight in freezing rain,

4) the FAA’s inadequate oversight of the ATR 42 and 72 to ensure continued airworthiness in icing conditions; and

5) ATR’s inadequate response to the continued occurrence of ATR 42 icing/roll upsets which, in conjunction with information learned about aileron control difficulties during the certification and development of the ATR 42 and 72, should have prompted additional research, and the creation of updated airplane flight manuals, flightcrew operating manuals and training programs related to operation of the ATR 42 and 72 in such icing conditions.