Crash of a Douglas DC-10-10 in Sioux City: 111 killed

Date & Time:

Jul 19, 1989 at 1600 LT

Registration:

N1819U

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Denver - Chicago - Philadelphia

MSN:

46618

YOM:

1971

Flight number:

UA232

Crew on board:

11

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

285

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

111

Captain / Total hours on type:

7190.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

665

Aircraft flight hours:

43401

Aircraft flight cycles:

16997

Circumstances:

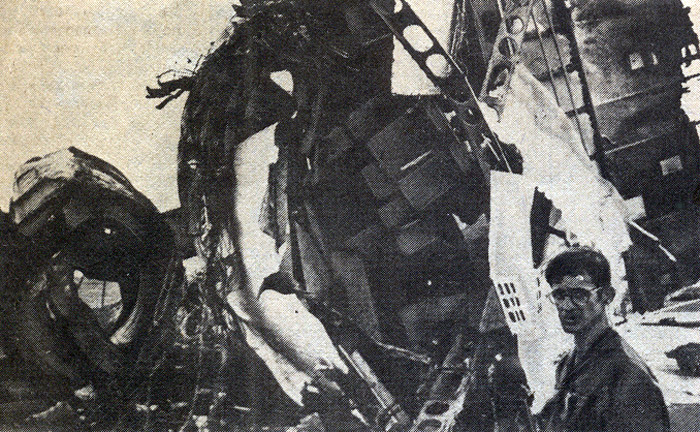

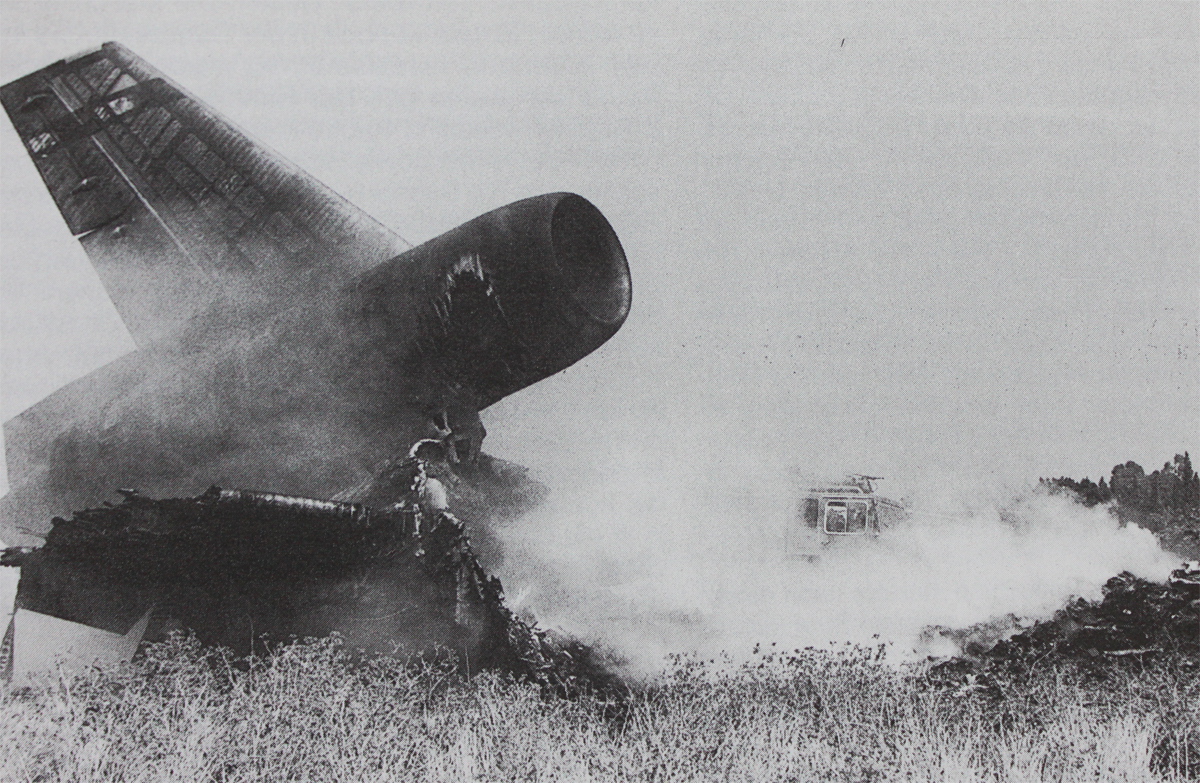

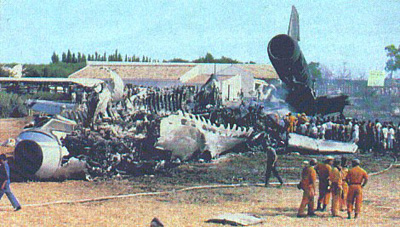

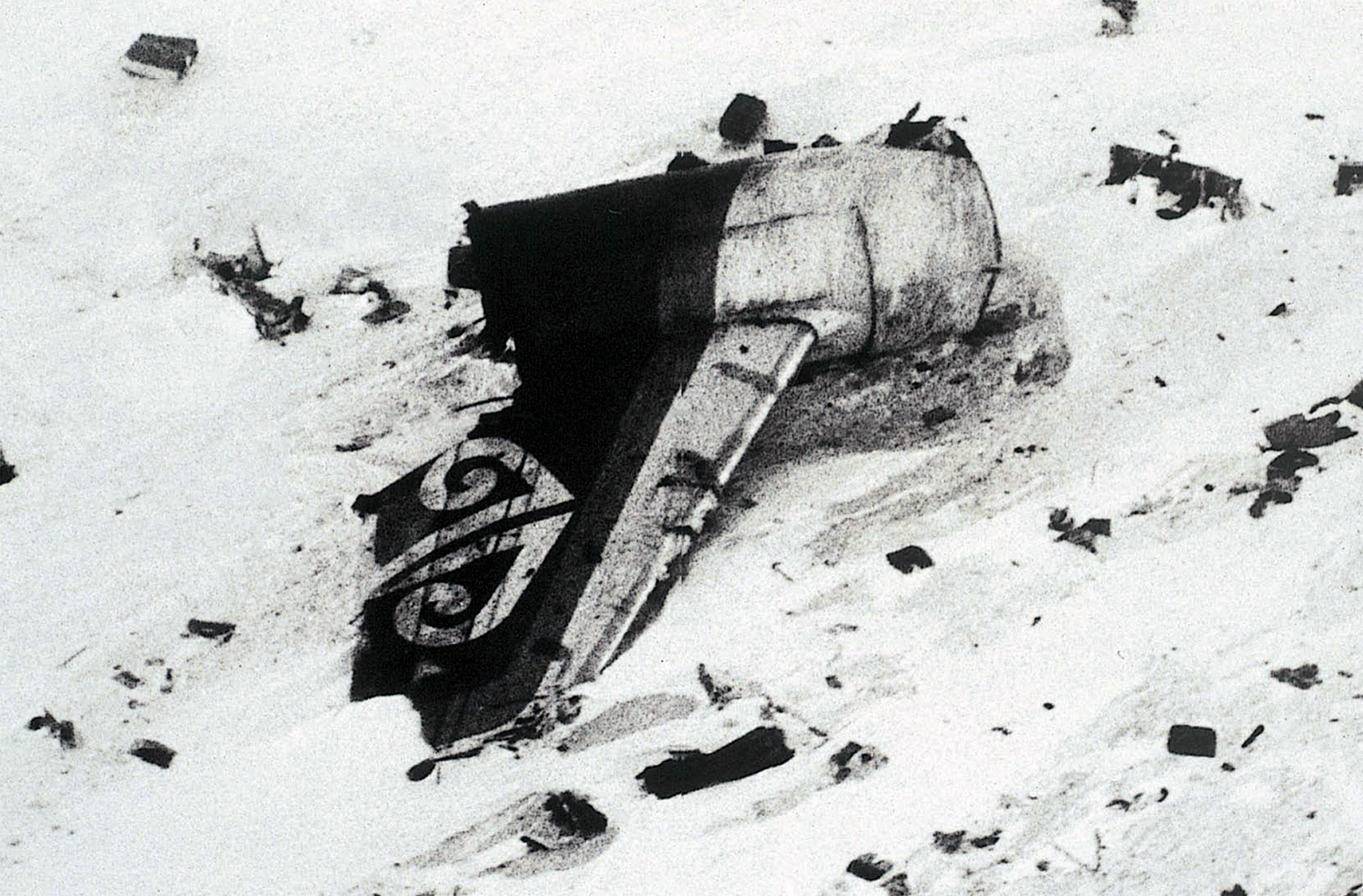

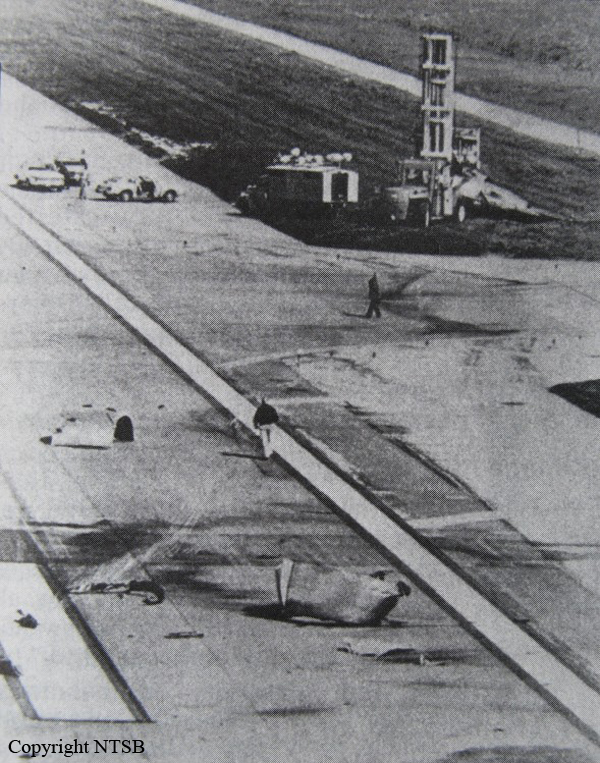

United Flight 232 departed Denver-Stapleton International Airport, Colorado, USA at 14:09 CDT for a domestic flight to Chicago-O'Hare, Illinois and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There were 285 passengers and 11 crew members on board. The takeoff and the en route climb to the planned cruising altitude of FL370 were uneventful. The first officer was the flying pilot. About 1 hour and 7 minutes after takeoff, at 15:16, the flightcrew heard a loud bang or an explosion, followed by vibration and a shuddering of the airframe. After checking the engine instruments, the flightcrew determined that the No. 2 aft (tail-mounted) engine had failed. The captain called for the engine shutdown checklist. While performing the engine shutdown checklist, the flight engineer observed that the airplane's normal systems hydraulic pressure and quantity gauges indicated zero. The first officer advised that he could not control the airplane as it entered a right descending turn. The captain took control of the airplane and confirmed that it did not respond to flight control inputs. The captain reduced thrust on the No. 1 engine, and the airplane began to roll to a wings-level attitude. The flightcrew deployed the air driven generator (ADG), which powers the No. 1 auxiliary hydraulic pump, and the hydraulic pump was selected "on." This action did not restore hydraulic power. At 15:20, the flightcrew radioed the Minneapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) and requested emergency assistance and vectors to the nearest airport. Initially, Des Moines International Airport was suggested by ARTCC. At 15:22, the air traffic controller informed the flightcrew that they were proceeding in the direction of Sioux City; the controller asked the flightcrew if they would prefer to go to Sioux City. The flightcrew responded, "affirmative." They were then given vectors to the Sioux Gateway Airport (SUX) at Sioux City, Iowa. A UAL DC-10 training check airman, who was off duty and seated in a first class passenger seat, volunteered his assistance and was invited to the cockpit at about 15:29. At the request of the captain, the check airman entered the passenger cabin and performed a visual inspection of the airplane's wings. Upon his return, he reported that the inboard ailerons were slightly up, not damaged, and that the spoilers were locked down. There was no movement of the primary flight control surfaces. The captain then directed the check airman to take control of the throttles to free the captain and first officer to manipulate the flight controls. The check airman attempted to use engine power to control pitch and roll. He said that the airplane had a continuous tendency to turn right, making it difficult to maintain a stable pitch attitude. He also advised that the No. 1 and No. 3 engine thrust levers could not be used symmetrically, so he used two hands to manipulate the two throttles. About 15:42, the flight engineer was sent to the passenger cabin to inspect the empennage visually. Upon his return, he reported that he observed damage to the right and left horizontal stabilizers. Fuel was jettisoned to the level of the automatic system cutoff, leaving 33,500 pounds. About 11 minutes before landing, the landing gear was extended by means of the alternate gear extension procedure. The flightcrew said that they made visual contact with the airport about 9 miles out. ATC had intended for flight 232 to attempt to land on runway 31, which was 8,999 feet long. However, ATC advised that the airplane was on approach to runway 22, which was closed, and that the length of this runway was 6,600 feet. Given the airplane's position and the difficulty in making left turns, the captain elected to continue the approach to runway 22 rather than to attempt maneuvering to runway 31. The check airman said that he believed the airplane was lined up and on a normal glidepath to the field. The flaps and slats remained retracted. During the final approach, the captain recalled getting a high sink rate alarm from the ground proximity warning system (GPWS). In the last 20 seconds before touchdown, the airspeed averaged 215 KIAS, and the sink rate was 1,620 feet per minute. Smooth oscillations in pitch and roll continued until just before touchdown when the right wing dropped rapidly. The captain stated that about 100 feet above the ground the nose of the airplane began to pitch downward. He also felt the right wing drop down about the same time. Both the captain and the first officer called for reduced power on short final approach. The check airman said that based on experience with no flap/no slat approaches he knew that power would have to be used to control the airplane's descent. He used the first officer's airspeed indicator and visual cues to determine the flightpath and the need for power changes. He thought that the airplane was fairly well aligned with the runway during the latter stages of the approach and that they would reach the runway. Soon thereafter, he observed that the airplane was positioned to the left of the desired landing area and descending at a high rate. He also observed that the right wing began to drop. He continued to manipulate the No. 1 and No. 3 engine throttles until the airplane contacted the ground. He said that no steady application of power was used on the approach and that the power was constantly changing. He believed that he added power just before contacting the ground. The airplane touched down on the threshold slightly to the left of the centerline on runway 22 at 16:00. First ground contact was made by the right wing tip followed by the right main landing gear. The airplane skidded to the right of the runway and rolled to an inverted position. Witnesses observed the airplane ignite and cartwheel, coming to rest after crossing runway 17/35. Firefighting and rescue operations began immediately, but the airplane was destroyed by impact and fire. The accident resulted in 111 fatal, 47 serious, and 125 minor injuries. The remaining 13 occupants were not injured.

Probable cause:

Inadequate consideration given to human factors limitations in the inspection and quality control procedures used by United Airlines' engine overhaul facility which resulted in the failure to detect a fatigue crack originating from a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the stage 1 fan disk that was manufactured by General Electric Aircraft Engines. The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk resulted in the liberation of debris in a pattern of distribution and with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic systems that operate the DC-10's flight controls.

Final Report: