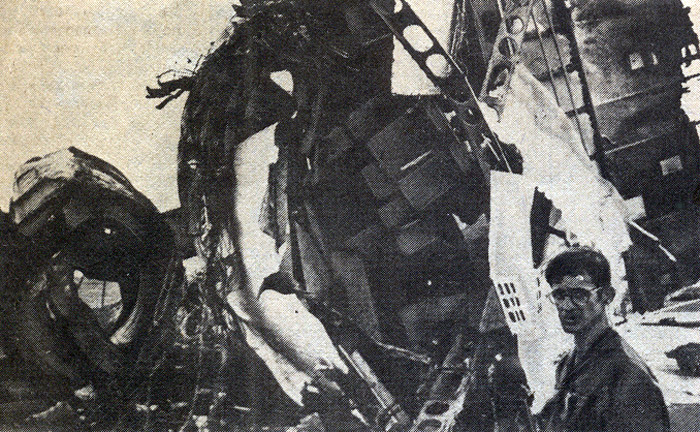

Crash of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air in Sioux City

Date & Time:

Jan 19, 2010 at 0715 LT

Registration:

N586BC

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Des Moines – Sioux City

MSN:

BB-1223

YOM:

1985

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

2

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

1831.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

2186

Aircraft flight hours:

10304

Circumstances:

The pilot of the Part 91 business flight filed an instrument-flight-rules (IFR) flight plan with the destination and alternate airports, both of which were below weather minimums. The pilot and

copilot departed from the departure airport in weather minimums that were below the approach minimums for the departure airport. While en route, the destination airport's automated observing system continued to report weather below approach minimums, but the flight crew continued the flight. The flight crew then requested and were cleared for the instrument landing system (ILS) 31 approach and while on that approach were issued visibilities of 1,800 feet runway visual range after changing to tower frequency. During landing, the copilot told the pilot that he was not lined up with the runway. The pilot reportedly said, "those are edge lights," and then realized that he was not properly lined up with the runway. The airplane then touched down beyond a normal touchdown point, about 2,800 feet down the runway, and off the left side of the runway surface. The airplane veered to the left, collapsing the nose landing gear. Both flight crewmembers had previous experience in Part 135 operations, which have more stringent weather requirements than operations conducted under Part 91. Under Part 135, IFR flights to an airport cannot be conducted and an approach cannot begin unless weather minimums are above approach minimums. The accident flight's departure in weather below approach minimums would have precluded a return to the airport had an emergency been encountered by the flight crew, leaving few options and little time to reach a takeoff alternate airport. The company's flight procedures allow for a takeoff to be performed as long as there is a takeoff alternate airport within one hour at normal cruise speed and a minimum takeoff visibility that was based upon the pilot being able to maintain runway alignment during takeoff. The company's procedures did not allow flight crew to depart to an airport that was below minimums but did allow for the flight crew, at their discretion, to

perform a "look-see" approach to approach minimums if the weather was below minimums. The allowance of a "look see" approach essentially negates the procedural risk mitigation afforded by requiring approaches to be conducted only when weather was above approach minimums.

copilot departed from the departure airport in weather minimums that were below the approach minimums for the departure airport. While en route, the destination airport's automated observing system continued to report weather below approach minimums, but the flight crew continued the flight. The flight crew then requested and were cleared for the instrument landing system (ILS) 31 approach and while on that approach were issued visibilities of 1,800 feet runway visual range after changing to tower frequency. During landing, the copilot told the pilot that he was not lined up with the runway. The pilot reportedly said, "those are edge lights," and then realized that he was not properly lined up with the runway. The airplane then touched down beyond a normal touchdown point, about 2,800 feet down the runway, and off the left side of the runway surface. The airplane veered to the left, collapsing the nose landing gear. Both flight crewmembers had previous experience in Part 135 operations, which have more stringent weather requirements than operations conducted under Part 91. Under Part 135, IFR flights to an airport cannot be conducted and an approach cannot begin unless weather minimums are above approach minimums. The accident flight's departure in weather below approach minimums would have precluded a return to the airport had an emergency been encountered by the flight crew, leaving few options and little time to reach a takeoff alternate airport. The company's flight procedures allow for a takeoff to be performed as long as there is a takeoff alternate airport within one hour at normal cruise speed and a minimum takeoff visibility that was based upon the pilot being able to maintain runway alignment during takeoff. The company's procedures did not allow flight crew to depart to an airport that was below minimums but did allow for the flight crew, at their discretion, to

perform a "look-see" approach to approach minimums if the weather was below minimums. The allowance of a "look see" approach essentially negates the procedural risk mitigation afforded by requiring approaches to be conducted only when weather was above approach minimums.

Probable cause:

The flight crew's decision to attempt a flight that was below takeoff, landing, and alternate airport weather minimums, which led to a touchdown off the runway surface by the pilot-in-command.

Final Report: