Circumstances:

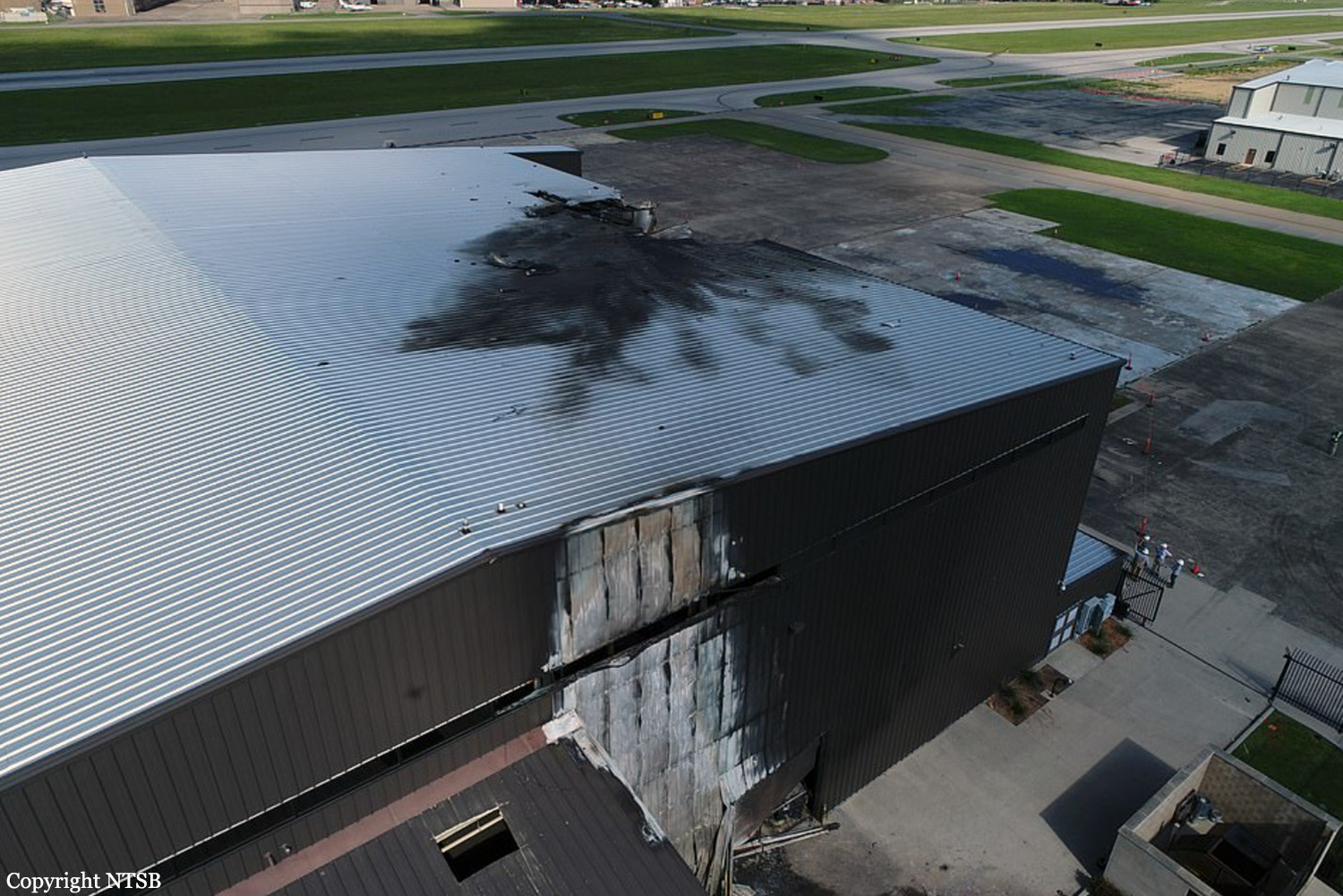

The pilot, co-pilot, and eight passengers departed on a cross-country flight in the twin-engine airplane. One witness located on the ramp at the airport reported that the airplane sounded underpowered immediately after takeoff “like it was at a reduced power setting.” Another witness stated that the airplane sounded like it did not have sufficient power to takeoff. A third witness described the rotation as “steep,” and other witnesses reported thinking that the airplane was performing aerobatics. Digital video from multiple cameras both on and off the airport showed the airplane roll to its left before reaching a maximum altitude of 100 ft above ground level; it then descended and impacted an airport hangar in an inverted attitude about 17 seconds after takeoff and an explosion immediately followed. After breaching a closed roll-up garage door, the airplane came to rest on its right side outside of the hangar and was immediately involved in a postimpact fire. Sound spectrum analysis of data from the airplane’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR) estimated that the propeller speeds were at takeoff power (1,714 to 1,728 rpm) at liftoff. About 7 seconds later, the propeller speeds diverged, with the left propeller speed decreasing to about 1,688 rpm and the right propeller speed decreasing to 1,707 rpm. Based on the airplane’s estimated calibrated airspeed of about 110 knots and the propeller rpm when the speeds diverged, the estimated thrust in the left engine decreased to near 0 while the right engine continued operating at slightly less than maximum takeoff power. Analysis of available data estimated that, 2 seconds after the propeller speed deviation, the airplane’s sideslip angle was nearly 20°. During the first 5 seconds after the propeller speed deviation, the airplane’s roll rate was about 5° per second to the left; its roll rate then rapidly increased to more than 60° per second before the airplane rolled inverted. Witness marks on the left engine and propeller, the reduction in propeller speed, and the airplane’s roll to the left suggest that the airplane most likely experienced a loss of thrust in the left engine shortly after takeoff. The airplane manufacturer’s engine-out procedure during takeoff instructed that the landing gear should be retracted once a positive rate of climb is established, and the propeller of the inoperative engine should be feathered. Right rudder should also be applied to balance the yawing moment imparted by a thrust reduction in the left engine. Examination of the wreckage found both main landing gear in a position consistent with being extended and the left propeller was unfeathered. The condition of the wreckage precluded determining whether the autofeather system was armed or activated during the accident flight. Thus, the pilot failed to properly configure the airplane once the left engine thrust was reduced. Calculations based on the airplane’s sideslip angle shortly after the propeller speed deviation determined that the thrust asymmetry alone was insufficient to produce the sideslip angle. Based on an evaluation of thrust estimates provided by the propeller manufacturer and performance data provided by the airplane manufacturer, it is likely that the pilot applied left rudder, the opposite input needed to maintain lateral control, before applying right rudder seconds later. However, by then, the airplane’s roll rate was increasing too rapidly, and its altitude was too low to recover. The data support that it would have been possible to maintain directional and lateral control of the airplane after the thrust reduction in the left engine if the pilot had commanded right rudder initially rather than left rudder. The pilot’s confused reaction to the airplane’s performance shortly after takeoff supports the possibility that he was startled by the stall warning that followed the propeller speed divergence, which may have prompted his initial, improper rudder input. In addition, the NTSB’s investigation estimated that rotation occurred before the airplane had attained Vr (rotation speed), which decreased the margin to the minimum controllable airspeed and likely lessened the amount of time available for the pilot to properly react to the reduction in thrust and maintain airplane control. Although the airplane was slightly over its maximum takeoff weight at departure, its rate of climb was near what would be expected at maximum weight in the weather conditions on the day of the accident (even with the extended landing gear adding drag); therefore, the weight exceedance likely was not a factor in the accident. Engine and propeller examinations and functional evaluations of the engine and propeller controls found no condition that would have prevented normal operation; evidence of operation in both engines at impact was found. Absent evidence of an engine malfunction, the investigation considered whether the left engine’s thrust reduction was caused by other means, such as uncommanded throttle movement due to an insufficient friction setting of the airplane’s power lever friction locks. Given the lack of callouts for checklists on the CVR and the pilot’s consistently reported history of not using checklists, it is possible that he did not check or adjust the setting of the power lever friction locks before the accident flight, which led to uncommanded movement of the throttle. Although the co-pilot reportedly had flown with the pilot many times previously and was familiar with the B-300, he was not type rated in the airplane and was not allowed by the pilot to operate the flight controls when passengers were on board. Therefore, the co-pilot may not have checked or adjusted the friction setting before the flight’s departure. Although the investigation considered inadequate friction setting the most likely cause of the thrust reduction in the left engine, other circumstances, such as a malfunction within the throttle control system, could also result in loss of engine thrust. However, heavy fire and impact damage to the throttle control system components, including the power quadrant and cockpit control lever friction components, precluded determining the position of the throttle levers at the time of the loss of thrust or the friction setting during the accident flight. Thus, the reason for the reduction in thrust could not be determined definitively. In addition to a lack of callouts for checklists on the CVR, the pilots did not discuss any emergency procedures. As a result, they did not have a shared understanding of how to respond to the emergency of losing thrust in an engine during takeoff. Although the co-pilot verbally identified the loss of the left engine in response to the pilot’s confused reaction to the airplane’s performance shortly after takeoff, it is likely the co-pilot did not initiate any corrective flight control inputs, possibly due to the pilot’s established practice of being the sole operator of flight controls when passengers were on board. The investigation considered whether fatigue from inadequately treated obstructive sleep apnea contributed to the pilot’s response to the emergency; however, the extent of any fatigue could not be determined from the available evidence. In addition, no evidence indicates that the pilot’s medical conditions or their treatment were factors in the accident. In summary, the available evidence indicates that the pilot improperly responded to the loss of thrust in the left engine by initially commanding a left rudder input and did not retract the landing gear or feather the left propeller, which was not consistent with the airplane manufacturer’s engine out procedure during takeoff. It would have been possible to maintain directional and lateral control of the airplane after the thrust reduction in the left engine if right rudder had been commanded initially rather than left rudder. It is possible that the pilot’s reported habit of not using checklists resulted in his not checking or adjusting the power lever friction locks as specified in the airplane manufacturer’s checklists. However, fire and impact damage precluded determining the position of the power levers or friction setting during the flight.