Crash of an ATR42-320 in Fond-du-Lac: 1 killed

Date & Time:

Dec 13, 2017 at 1812 LT

Registration:

C-GWEA

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Saskatoon – Prince Albert – Fond-du-Lac – Stony Rapids

MSN:

240

YOM:

1991

Flight number:

WEW280

Crew on board:

3

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

22

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

1

Captain / Total hours on type:

1500.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

7930

Aircraft flight hours:

26481

Aircraft flight cycles:

32051

Circumstances:

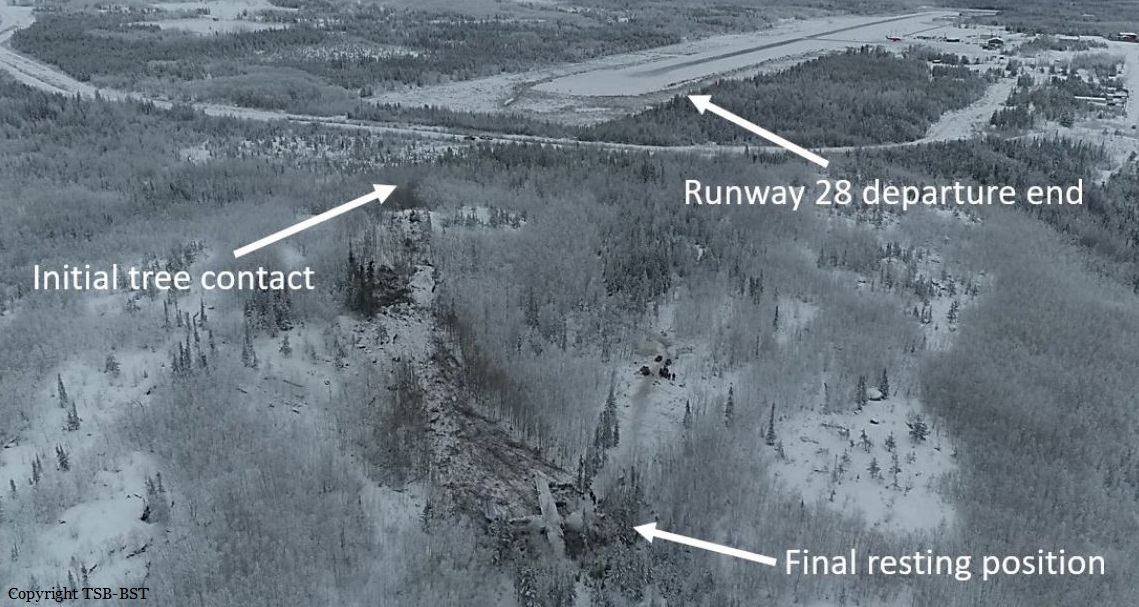

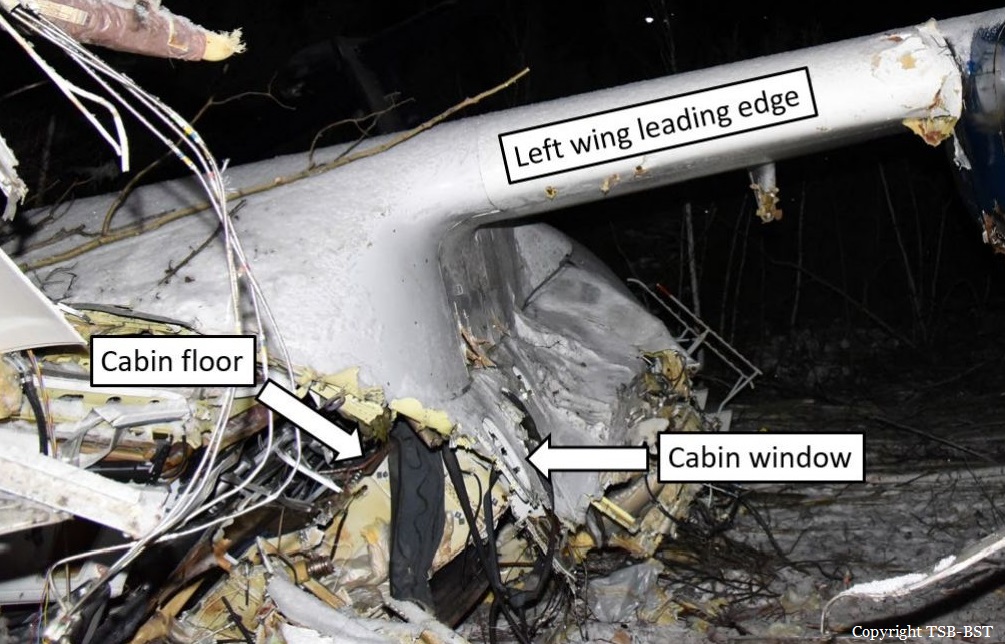

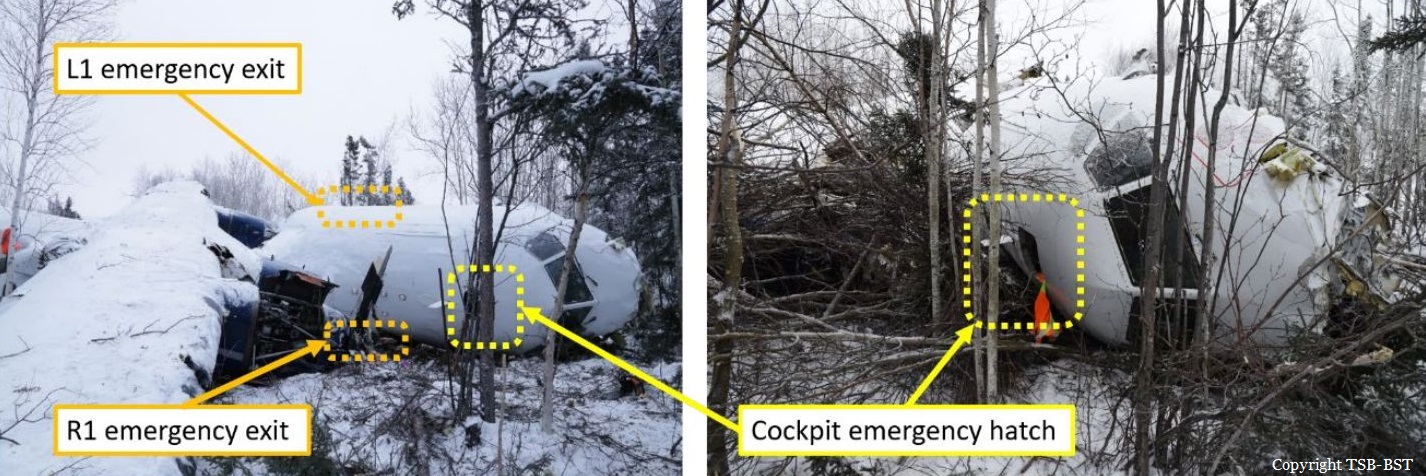

On 13 December 2017, an Avions de Transport Régional ATR 42-320 aircraft (registration C-GWEA, serial number 240), operated by West Wind Aviation L.P. (West Wind), was scheduled for a series of instrument flight rules flights from Saskatoon through northern Saskatchewan as flight WEW282. When the flight crew and dispatcher held a briefing for the day’s flights, they became aware of forecast icing along the route of flight. Although both the flight crew and the dispatcher were aware of the forecast ground icing, the decision was made to continue with the day’s planned route to several remote airports that had insufficient de-icing facilities. The aircraft flew from Saskatoon/John G. Diefenbaker International (CYXE) to Prince Albert (Glass Field) Airport (CYPA) without difficulty, and, after a stop of about 1 hour, proceeded on toward Fond-du-Lac Airport (CZFD). On approach to Fond-du-Lac Airport, the aircraft encountered some in-flight icing, and the crew activated the aircraft’s anti-icing and de-icing systems. Although the aircraft’s ice protection systems were activated, the aircraft’s de-icing boots were not designed to shed all of the ice that can accumulate, and the anti-icing systems did not prevent ice accumulation on unprotected surfaces. As a result, some residual ice began to accumulate on the aircraft. The flight crew were aware of the ice; however, there were no handling anomalies noted during the approach. Consequently, they likely did not assess that the residual ice was severe enough to have a significant effect on aircraft performance. The crew continued the approach and landed at Fond-du-Lac Airport at 1724 Central Standard Time. According to post-accident analysis of the data from the flight data recorder, the aircraft’s drag and lift performance was degraded by 28% and 10%, respectively, shortly before landing at Fond-du-Lac Airport. This indicated that the aircraft had significant residual ice adhering to its structure upon arrival. However, this data was not available to the flight crew at the time of landing. The aircraft was on the ground at Fond-du-Lac Airport for approximately 48 minutes. The next flight was destined for Stony Rapids Airport (CYSF), Saskatchewan, with 3 crew members (2 pilots and 1 flight attendant) and 22 passengers on board. Although there was no observable precipitation or fog while the aircraft was on the ground, weather conditions were conducive to ice or frost formation. This, combined with the residual mixed ice on the aircraft, which acted as nucleation sites that allowed the formation of ice crystals, resulted in the formation of additional ice or frost on the aircraft’s critical surfaces. Once the passengers had boarded the aircraft, the first officer completed an external inspection of the aircraft. However, because the available inspection equipment was inadequate, the first officer’s ice inspection consisted only of walking around the aircraft and looking at the left wing from the top of the stairs at the left rear door, without the use of a flashlight on the dimly lit apron. Although he was unaware of the full extent of the ice and the ongoing accretion, the first officer did inform the captain that there was some ice on the aircraft. The captain did not inspect the aircraft himself, nor did he attempt to have it de-iced; rather, he and the first officer continued with departure preparations. Company departures from remote airports, such as Fond-du-Lac, with some amount of surface contamination on the aircraft’s critical surfaces had become common practice, in part due to the inadequacy of de-icing equipment or services at these locations. The past success of these adaptations resulted in this unsafe practice becoming normalized and this normalization influenced the flight crew’s decision to depart. Although the flight crew were aware of icing on the aircraft’s critical surfaces, they decided that the occurrence departure could be accomplished safely. Their decision to continue with the original plan to depart was influenced by continuation bias, as they perceived the initial and sustained cues that supported their plan as more compelling than the later cues that suggested another course of action. At 1812 Central Standard Time, in the hours of darkness, the aircraft began its take-off roll on Runway 28, and, 30 seconds later, it was airborne. As a result of the ice that remained on the aircraft following the approach and the additional ice that had accreted during the ground stop, the aircraft’s drag was increased by 58% and its lift was decreased by 25% during the takeoff. Despite this degraded performance, the aircraft initially climbed; however, immediately after liftoff, the aircraft began to roll to the left without any pilot input. This roll was as a result of asymmetric lift distribution due to uneven ice contamination on the aircraft. Following the uncommanded roll, the captain reacted as if the aircraft was an uncontaminated ATR 42, with the expectation of normal handling qualities and dynamic response characteristics; however, due to the contamination, the aircraft had diminished roll damping resulting in unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response. Although the investigation determined that the ailerons had sufficient roll control authority to counteract the asymmetric lift, due to the unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response, the roll disturbance developed into an oscillation with growing magnitude and control in the roll axis was lost. This loss of control in the roll axis, which corresponds with the known risks associated with taking off with ice contamination, ultimately led to the aircraft colliding with terrain 17 seconds after takeoff. The aircraft collided with the ground in a relatively level pitch, with a bank angle of 30° left. As a result of the sudden vertical deceleration upon contact with the ground, the aircraft suffered significant damage, which varied in severity at different locations on the aircraft due to impact angle and variability in structural design. The design standards for transport category aircraft in effect at the time the ATR 42 was certified did not specify minimum loads that a fuselage structure must be able to tolerate and remain survivable, or minimum loads for fuselage impact energy absorption. As a result, the ATR 42 was not designed with these crashworthy principles in mind. The main landing gear at the bottom of the centre fuselage section was rigid, and, on impact, did not absorb or attenuate much of the load. The impact-induced acceleration was not attenuated because the landing gear housing did not deform. This unattenuated acceleration resulted in a large inertial load from the wing, causing the wing support structure to fail and the wing to collapse into the cabin. The reduced survivable space between the floor above the main landing gear and the collapsed upper fuselage caused crushing injuries, such as major head, body, and leg trauma, to passengers in the middle-forward left section of the aircraft. Of the 3 passengers in this area, 2 experienced, serious life-changing injuries, and 1 passenger subsequently died. The collapse of part of the floor structure compromised the restraint systems, limiting the protection afforded to the aircraft occupants when they were experiencing vertical, longitudinal, and lateral forces. This resulted in serious velocity-related injuries and impeded their ability to take post-crash survival actions in a timely manner. Unaware of the danger, most passengers in this occurrence did not brace for impact. Because their torsos were unrestrained, they received injuries consistent with jackknifing and flailing, such as hitting the seat in front of them. As a result of unapproved repairs, the flight attendant seat failed on impact, resulting in injuries that impeded her ability to perform evacuation and survival actions in a timely manner. Although the TSB has previously recommended the development and use of child restraints aboard commercial aircraft, planned regulations have yet to be implemented by Transport Canada. As a result, the occurrence aircraft was not equipped with these devices, and an infant passenger who was unrestrained received flailing and crushing injuries during the accident sequence. By the time the aircraft came to a rest, all occupants had received injuries. Passengers began to call for help within minutes of the impact, using their cell phones. Numerous people from the nearby community received the messages and quickly set out to help. The passengers and crew began to evacuate, but they experienced significant difficulties as a result of the aircraft damage. It took approximately 20 minutes for the first 17 passengers to evacuate, and the remaining passengers much longer; it took as long as 3 hours to extricate 1 passenger, who required rescuer assistance. As a result of the accident, 9 passengers and 1 crew member received serious injuries, and the remaining 13 passengers and 2 crew members received minor injuries. One of the passengers who had received serious injuries died 12 days after the accident. There was no post-impact fire, and the emergency locator activated on impact.

Probable cause:

Findings as to causes and contributing factors:

These are conditions, acts or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

1. When West Wind commenced operations into Fond-du-Lac Airport (CZFD) in 2014, no effective risk controls were in place to mitigate the potential hazard of ground icing at CZFD.

2. Although both the flight crew and the dispatcher were aware of the forecast ground icing, the decision was made to continue with the day’s planned route to several remote airports that had insufficient de-icing facilities.

3. Although the aircraft’s ice-protection systems were activated on the approach to CZFD, the aircraft’s de-icing boots were not designed to shed all of the ice that can accumulate, and the anti-icing systems did not prevent ice accumulation on unprotected surfaces. As a result, some residual ice began to accumulate on the aircraft.

4. Although the flight crew were aware of the ice, there were no handling anomalies noted on the approach. Consequently, the crew likely did not assess that the residual ice was severe enough to have a significant effect on aircraft performance. Subsequently, without any further discussion about the icing, the crew continued the approach and landed at CZFD.

5. Weather conditions on the ground were conducive to ice or frost formation, and this, combined with the nucleation sites provided by the residual mixed ice on the aircraft, resulted in the formation of additional ice or frost on the aircraft’s critical surfaces.

6. Because the available inspection equipment was inadequate, the first officer’s ice inspection consisted only of walking around the aircraft on a dimly lit apron, without a flashlight, and looking at the left wing from the top of the stairs at the left rear entry door (L2). As a result, the full extent of the residual ice and ongoing accretion was unknown to the flight crew.

7. Departing from remote airports, such as CZFD, with some amount of surface contamination on the aircraft’s critical surfaces, had become common practice, in part due to the inadequacy of de-icing equipment or services at these locations. The past success of these adaptations resulted in the unsafe practice becoming normalized and this normalization influenced the flight crew’s decision to depart.

8. Although the flight crew were aware of icing on the aircraft’s critical surfaces, they decided that the occurrence departure could be accomplished safely. Their decision to continue with the original plan to depart was influenced by continuation bias, as they perceived the initial and sustained cues that supported their plan as more compelling than the later cues that suggested another course of action.

9. As a result of the ice that remained on the aircraft following the approach and the additional ice that had accreted during the ground stop, the aircraft’s drag was

increased by 58% and its lift was decreased by 25% during the takeoff.

10. During the takeoff, despite the degraded performance, the aircraft initially climbed; however, immediately after lift off, the aircraft began to roll to the left without any pilot input. This roll was as a result of asymmetric lift distribution due to uneven ice contamination on the aircraft.

11. Following the uncommanded roll, the captain reacted as if the aircraft was an uncontaminated ATR 42, with the expectation of normal handling qualities and dynamic response characteristics; however, due to the contamination, the aircraft had diminished roll damping resulting in unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response.

12. Although the investigation determined the ailerons had sufficient roll control authority to counteract the asymmetric lift, due to the unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response, the roll disturbance developed into an oscillation with growing magnitude and control in the roll axis was lost.

13. This loss of control in the roll axis, which corresponds with the known risks associated with taking off with ice contamination, ultimately led to the aircraft colliding with terrain.

14. The aircraft collided with the ground in relatively level pitch, with a bank angle of 30° left. As a result of the sudden vertical deceleration upon contact with the ground, the aircraft suffered significant damage, which varied in severity at different locations on the aircraft because of the impact angle and the variability in structural design.

15. The design standards for transport category aircraft in effect at the time the ATR 42 was certified did not specify minimum loads that a fuselage structure must be able to tolerate and remain survivable, or minimum loads for fuselage impact energy absorption. As a result, the ATR 42 was not designed with these crashworthy principles in mind.

16. On impact, the induced acceleration was not attenuated because the landing gear housing did not deform. This unattenuated acceleration resulted in a large inertial load from the wing, causing the wing support structure to fail and the wing to collapse into the cabin.

17. The reduced survivable space between the floor above the main landing gear and the collapsed upper fuselage caused crushing injuries, such as major head, body, and leg trauma, to passengers in the middle-forward left section of the aircraft. Of the 3 passengers in this area, 2 experienced serious life-changing injuries, and 1 passenger died.

18. The collapse of part of the floor structure compromised the restraint systems, limiting the protection afforded to the occupants when they were experiencing vertical, longitudinal, and lateral forces. This resulted in serious velocity-related injuries and impeded their ability to take post-impact survival actions in a timely manner.

19. Most passengers in this occurrence did not brace before impact. Because their torsos were unrestrained, they received injuries consistent with jackknifing and flailing, such as hitting the seat in front of them.

20. Given that regulations requiring the use of child-restraint systems have yet to be implemented, the aircraft was not equipped with these devices. As a result, the infant passenger was unrestrained and received flail and crushing injuries. 21. As a result of unapproved repairs, the flight attendant seat failed on impact, resulting in injuries that impeded her ability to perform evacuation and survival actions in a timely manner.

These are conditions, acts or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

1. When West Wind commenced operations into Fond-du-Lac Airport (CZFD) in 2014, no effective risk controls were in place to mitigate the potential hazard of ground icing at CZFD.

2. Although both the flight crew and the dispatcher were aware of the forecast ground icing, the decision was made to continue with the day’s planned route to several remote airports that had insufficient de-icing facilities.

3. Although the aircraft’s ice-protection systems were activated on the approach to CZFD, the aircraft’s de-icing boots were not designed to shed all of the ice that can accumulate, and the anti-icing systems did not prevent ice accumulation on unprotected surfaces. As a result, some residual ice began to accumulate on the aircraft.

4. Although the flight crew were aware of the ice, there were no handling anomalies noted on the approach. Consequently, the crew likely did not assess that the residual ice was severe enough to have a significant effect on aircraft performance. Subsequently, without any further discussion about the icing, the crew continued the approach and landed at CZFD.

5. Weather conditions on the ground were conducive to ice or frost formation, and this, combined with the nucleation sites provided by the residual mixed ice on the aircraft, resulted in the formation of additional ice or frost on the aircraft’s critical surfaces.

6. Because the available inspection equipment was inadequate, the first officer’s ice inspection consisted only of walking around the aircraft on a dimly lit apron, without a flashlight, and looking at the left wing from the top of the stairs at the left rear entry door (L2). As a result, the full extent of the residual ice and ongoing accretion was unknown to the flight crew.

7. Departing from remote airports, such as CZFD, with some amount of surface contamination on the aircraft’s critical surfaces, had become common practice, in part due to the inadequacy of de-icing equipment or services at these locations. The past success of these adaptations resulted in the unsafe practice becoming normalized and this normalization influenced the flight crew’s decision to depart.

8. Although the flight crew were aware of icing on the aircraft’s critical surfaces, they decided that the occurrence departure could be accomplished safely. Their decision to continue with the original plan to depart was influenced by continuation bias, as they perceived the initial and sustained cues that supported their plan as more compelling than the later cues that suggested another course of action.

9. As a result of the ice that remained on the aircraft following the approach and the additional ice that had accreted during the ground stop, the aircraft’s drag was

increased by 58% and its lift was decreased by 25% during the takeoff.

10. During the takeoff, despite the degraded performance, the aircraft initially climbed; however, immediately after lift off, the aircraft began to roll to the left without any pilot input. This roll was as a result of asymmetric lift distribution due to uneven ice contamination on the aircraft.

11. Following the uncommanded roll, the captain reacted as if the aircraft was an uncontaminated ATR 42, with the expectation of normal handling qualities and dynamic response characteristics; however, due to the contamination, the aircraft had diminished roll damping resulting in unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response.

12. Although the investigation determined the ailerons had sufficient roll control authority to counteract the asymmetric lift, due to the unexpected handling qualities and dynamic response, the roll disturbance developed into an oscillation with growing magnitude and control in the roll axis was lost.

13. This loss of control in the roll axis, which corresponds with the known risks associated with taking off with ice contamination, ultimately led to the aircraft colliding with terrain.

14. The aircraft collided with the ground in relatively level pitch, with a bank angle of 30° left. As a result of the sudden vertical deceleration upon contact with the ground, the aircraft suffered significant damage, which varied in severity at different locations on the aircraft because of the impact angle and the variability in structural design.

15. The design standards for transport category aircraft in effect at the time the ATR 42 was certified did not specify minimum loads that a fuselage structure must be able to tolerate and remain survivable, or minimum loads for fuselage impact energy absorption. As a result, the ATR 42 was not designed with these crashworthy principles in mind.

16. On impact, the induced acceleration was not attenuated because the landing gear housing did not deform. This unattenuated acceleration resulted in a large inertial load from the wing, causing the wing support structure to fail and the wing to collapse into the cabin.

17. The reduced survivable space between the floor above the main landing gear and the collapsed upper fuselage caused crushing injuries, such as major head, body, and leg trauma, to passengers in the middle-forward left section of the aircraft. Of the 3 passengers in this area, 2 experienced serious life-changing injuries, and 1 passenger died.

18. The collapse of part of the floor structure compromised the restraint systems, limiting the protection afforded to the occupants when they were experiencing vertical, longitudinal, and lateral forces. This resulted in serious velocity-related injuries and impeded their ability to take post-impact survival actions in a timely manner.

19. Most passengers in this occurrence did not brace before impact. Because their torsos were unrestrained, they received injuries consistent with jackknifing and flailing, such as hitting the seat in front of them.

20. Given that regulations requiring the use of child-restraint systems have yet to be implemented, the aircraft was not equipped with these devices. As a result, the infant passenger was unrestrained and received flail and crushing injuries. 21. As a result of unapproved repairs, the flight attendant seat failed on impact, resulting in injuries that impeded her ability to perform evacuation and survival actions in a timely manner.

Final Report: