Crash of a BAc 111-201AC in Milan

Date & Time:

Jan 14, 1969 at 2032 LT

Registration:

G-ASJJ

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Milan - London

MSN:

14

YOM:

1965

Crew on board:

7

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

26

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

2153.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

497

Aircraft flight hours:

8310

Circumstances:

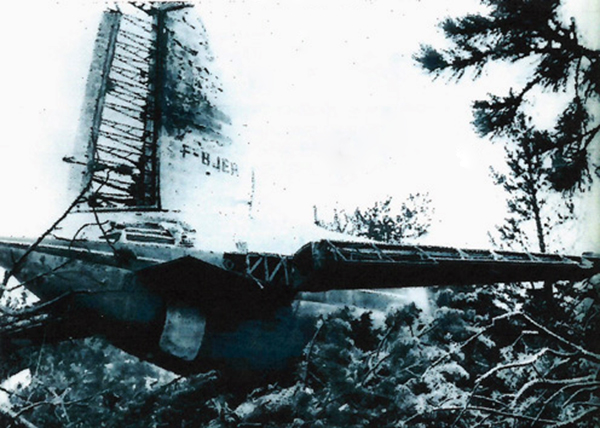

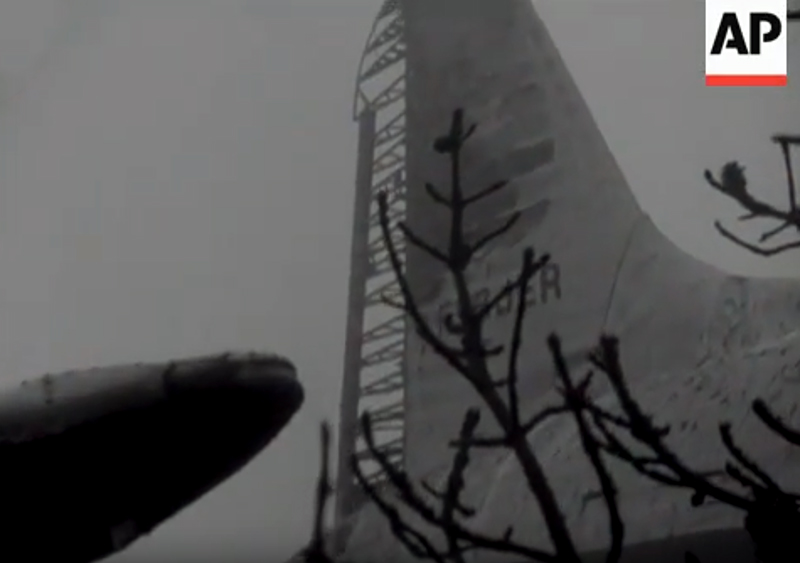

On 14 January 1969 the crew flew from Gatwick to Rotterdam and return, following which they departed on a scheduled international flight Gatwick-Genoa-Gatwick. For this flight Captain A occupied the left-hand seat as pilot-in-charge, Captain B the right hand seat as co-pilot and Captain C the centre supernumerary seat as pilot-in-command, ultimately responsible for the correct operation of the aircraft. Before leaving Gatwick Captain A briefed Captain B concerning the co-pilot duties assigned to him. Although Captain C, as pilot-in-command, did not himself formally brief Captains A and B there was no doubt that they were aware of their respective tasks. On the flight from Gatwick to Genoa the aircraft was forced, due to unfavourable weather conditions at Genoa, to divert to Milan-Linate Airport where it landed at 1430 hours. Before commencing the return flight to Gatwick the crew had to await the arrival of the passengers from Genoa. This took place at 1930 hours. During the five-hour waiting period on the ground, the aircraft APU was kept in operation to ensure cabin heating and air conditioning. While Captain C tried unsuccessfully to sleep in the aircraft, Captains A and B inspected the aircraft and found ice on the wings and tail unit. The aircraft was subsequently de-iced. Before boarding the aircraft, Captains A and B made another external inspection of the aircraft and established that there was no ice on any part of it. The result of this inspection was duly reported to Captain C. Captains A and B carried out the pre-flight checks in accordance with the company checklist and verified that the take-off weight and aircraft loading were within the permitted limits. The crew occupied the same positions as during the previous flight, Captain A being in the left-hand seat, Captain B in the right-hand seat and Captain C in the jump- seat. In view of the weather, temperature and runway conditions, the crew decided to use the 18O flap setting, Spey 2 thrust (full thrust), engine anti-icing and the APU for cabin air conditioning. V1 and Vr were established at 117 kt and V2 at 127 kt. At 2018 hours, after clearance from Linate ATC, the engines were started and engine anti-icing selected "ON". There was a considerable layer of snow along the sides of the taxiways and runway, but they themselves were clear and usable. In view of the isolated patches of slush or water on the runway, Captain A considered it essential for the engine igniter switches to be selected "ON" during the entire take-off. At 2028 hours the aircraft was cleared to enter runway 18 and, after receiving the latest information concerning visibility and wind, it was cleared for take-off at 2031 hours. Before the brakes were released, a check was made of engine P7 pressures and of the other engine instruments which were found to be normal. At about 80 kt Captain A took over the aircraft's control column. The airspeed indicators showed regular acceleration and Captain A stated that just before 100 kt the engine instruments were also registering normally. V1 and Vr were called and the aircraft was rotated into the initial climbing attitude; immediately after or during this manoeuvre, a dull noise was distinctly heard by all the crew members. This noise was variously described by them as: "not like a rifle shot, not like the slamming of a door or something falling in the aircraft but more like someone kicking the fuselage with very heavy boots, an expansive noise covering a very definite time span with a dull non-metallic thud". The bang was immediately associated by the crew with the engines. After looking at the TGT gauges, and observing that No. 1 engine was indicating a temperature 20°c higher than that of No. 2 engine, Captain C said: "I think it's number one" or wards to that effect, and after a brief pause "throttle it". On receipt of Captain C's comment Captain A closed the power level of No. 1 engine. During or just after the explosion, he had completed the rotation manoeuvre and the aircraft was climbing at 12O of pitch with reference to the flight director. As a precaution, after closing No. 1 power lever he reduced the angle of climb to 6O. At the same time the co-pilot (Captain B) who had reached for the check list and was looking for the page relating to an engine emergency, became aware of a sharp reduction in the aircraft's acceleration; he noticed that the undercarriage was still down and he retracted it immediately. According to the crew the aircraft reached a maximum height of 250 ft, after which a progressive loss of momentum became evident. A maximum speed of 1401145 kt was achieved immediately after rotation, but it fell to 127 kt after No. 1 engine had been throttled back, These figures were consistent with those subsequently derived from the flight recorder. The crew said that the stick-shaker operated three times between 125 and 115 kt. The co-pilot had a vague recollection that the stick-push and the warning klaxon operated during the critical phase before impact. The pilot-in-charge remembered vaguely that someone said "raise the flaps", but no crew member remembers doing so or making the re traction. On looking out of the aircraft the crew saw the ground and the obstructions close at hand and realized that contact of the aircraft with the ground was inevitable and imminent. Captain A controlled the aircraft extremely well during the touchdown; the aircraft slid along the snow-covered surface, passing over small obstructions, and came to a halt 470 m from the point of first contact with the ground (see Fig. 1-11. The co-pilot operated both engine fire-extinguishers and Captain C ordered the pilots to leave the aircraft immediately via the side windows. During the ground slide an orange glow was seen to light up the glass panels of the windows for a short time. There was no fire. After closing No. 1 power lever, Captain A remembered having ordered the shutdown drill for this engine but he could not say for certain whether this wae dme. It was established, however, that Captain B closed both the HP cocks at the first sensation of ground contact.

Probable cause:

The accident must be attributed to a combination of factors following a compressor bang/surge in No. 2 engine immediately after take-off and the aircraft crashed because the crew, after fully closing No. 1 throttle in error, failed to recognize their mistake and, in addition, were not aware that the thrust of No. 2 engine had also been partially reduced after an inadvertent displacement of the relevant throttle lever. The following findings were reported:

- A segment of the HP turbine seal of No. 2 engine caused a compressor bang/ surge which led the crew to think that there was a serious engine malfunction. The loss of thrust attributable to this defect was negligible,

- Tests have shown that there were no defects or failures of the engine fuel system or fuel controls which could be associated with the loss of thrust over and above that resulting from the deliberate throttling of No. 1 engine,

- N° 1 engine was throttled back after an erroneous order or piece of advice and its throttle lever was pulled rearwards rapidly,

- The major loss of thrust in No. 2 engine was probably due to the displacement of the throttle lever by a crew member and to the fact that its partially open position remained unnoticed during the period of confusion preceding the emergency landing,

- The incorrect diagnosis of a malfunction of No. 1 engine after the bangleurge can be attributed to the hasty intervention of the pilot-in-command and this could be attributed to fatigue, aggravated by the long duty period,

- In rapidly throttling back No. 1 engine, the pilot-in-charge promptly executed without question what he thought to be an order instead of waiting until a greater height was reached and then taking any appropriate action,

- The judgement and actions of the pilot-in-charge were influenced by the presence of an experienced pilot designated as pilot-in-command, although the latter's specific task was the supervision of the co-pilot,

- If the aircraft pilot-in-command had been seated at the controls, he might have acted correctly; similarly, if he had been responsible solely for the supervision of the co-pilot and had not been designated as pilot-in-command, the pilot-in-charge would have had a wider and more responsible field of action and would very probably have complied with the company's prescribed drills.

- A segment of the HP turbine seal of No. 2 engine caused a compressor bang/ surge which led the crew to think that there was a serious engine malfunction. The loss of thrust attributable to this defect was negligible,

- Tests have shown that there were no defects or failures of the engine fuel system or fuel controls which could be associated with the loss of thrust over and above that resulting from the deliberate throttling of No. 1 engine,

- N° 1 engine was throttled back after an erroneous order or piece of advice and its throttle lever was pulled rearwards rapidly,

- The major loss of thrust in No. 2 engine was probably due to the displacement of the throttle lever by a crew member and to the fact that its partially open position remained unnoticed during the period of confusion preceding the emergency landing,

- The incorrect diagnosis of a malfunction of No. 1 engine after the bangleurge can be attributed to the hasty intervention of the pilot-in-command and this could be attributed to fatigue, aggravated by the long duty period,

- In rapidly throttling back No. 1 engine, the pilot-in-charge promptly executed without question what he thought to be an order instead of waiting until a greater height was reached and then taking any appropriate action,

- The judgement and actions of the pilot-in-charge were influenced by the presence of an experienced pilot designated as pilot-in-command, although the latter's specific task was the supervision of the co-pilot,

- If the aircraft pilot-in-command had been seated at the controls, he might have acted correctly; similarly, if he had been responsible solely for the supervision of the co-pilot and had not been designated as pilot-in-command, the pilot-in-charge would have had a wider and more responsible field of action and would very probably have complied with the company's prescribed drills.

Final Report: