Crash of a Piper PA-31-350 Navajo Chieftain in Hillcrest

Date & Time:

Apr 7, 2023 at 0605 LT

Registration:

VH-HJE

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Bankstown – Brisbane

MSN:

31-7852074

YOM:

1978

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

204.00

Circumstances:

On 7 April 2023, the pilot of a Piper Aircraft Corporation PA-31-350 Chieftain (PA-31), registered VH-HJE and operated by Air Link, was conducting a freight charter flight from Archerfield, Queensland. The planned flight included one intermediate stop at Bankstown, New South Wales before returning to Archerfield, and was conducted under the instrument flight rules at night. The aircraft departed Archerfield at about 0024 local time and during the first leg to Bankstown, the pilot reported an intermittent fault with the autopilot, producing uncommanded pitch changes and associated rates of climb and descent of around 1,000 ft/min. As a result, much of the first leg was flown by hand. After landing at Bankstown at about 0248, a defect entry was made on the maintenance release; however, the pilot was confident that they would be able to hand fly the aircraft for the return leg and elected to continue with the planned flight. The aircraft was refueled to its maximum capacity for the return leg after which a small quantity of water was detected in the samples taken from both main fuel tanks. Additional fuel drains were conducted until the fuel sample was free of water. The manifested freight for the return leg was considered a light load and the aircraft was within weight and balance limitations. After taking off at 0351, the pilot climbed to the flight planned altitude of 9,000 ft. Once established in cruise, the pilot changed the left and right fuel selectors from the respective main tank to the auxiliary tank. The pilot advised that, during cruise, they engaged the autopilot and the uncommanded pitch events continued. Consequently, the pilot did not use the autopilot for part of the flight. Approaching top of descent, the pilot recalled conducting their normal flow checks by memory before referring to the checklist. During this time, the pilot completed a number of other tasks not related to the fuel system, such as changing the radio frequency, checking the weather at the destination and briefing themselves on the expected arrival into Archerfield. Shortly after, the pilot remembered changing from the auxiliary fuel tanks back to the main fuel tanks and using the fuel quantity gauges to confirm tank selection. The pilot calculated that 11 minutes of fuel remained in the auxiliary tanks (with an estimated 177 L in each main tank). Around eight minutes after commencing descent and 28 NM (52 km) south of Archerfield (at 0552), the pilot observed the right ‘low fuel flow’ warning light (or ‘low fuel pressure’) illuminate on the annunciator panel. This was followed soon after by a slight reduction in noise from the right engine. As the aircraft descended through approximately 4,700 ft, the ADS-B data showed a moderate deceleration with a gradual deviation right of track. While the power loss produced a minor yaw to the right, the pilot recalled that only a small amount of rudder input was required to counter the adverse yaw once the autopilot was disconnected. Without any sign of rough running or engine surging, they advised that had they not seen the annunciator light, they would not have thought there was a problem. Over the next few minutes, the pilot attempted to troubleshoot and diagnose the problem with the right engine. Immediately following power loss, the pilot reported they:

• switched on both emergency fuel boost pumps

• advanced both mixture levers to RICH

• cycled the throttle to full throttle and then returned it to its previous setting without fully closing the throttle

• moved the right fuel selector from main tank to auxiliary

• disconnected the autopilot and retrimmed the aircraft. This did not alter the abnormal operation of the right engine, and the pilot conducted the engine roughness checklist from the aircraft pilot’s operating handbook noting the following:

• oil temperature, oil pressure, and cylinder head temperature indicated normally

• manifold absolute pressure (MAP) had decreased from 31 in Hg to 27 inHg

• exhaust gas temperature (EGT) indicated in the green range

• fuel flow indicated zero.

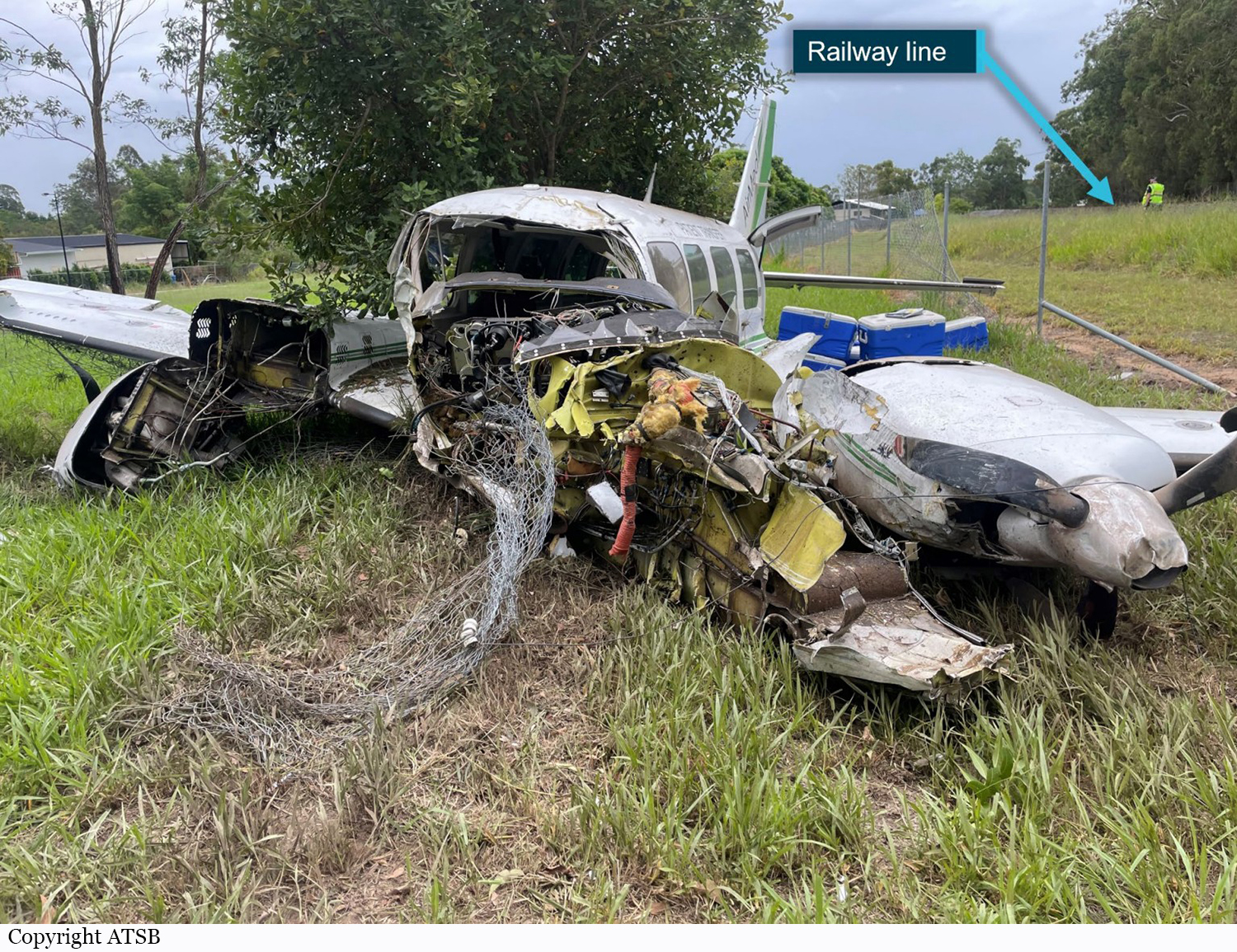

With no indication of mechanical failure, the pilot advised they could not rule out the possibility of fuel contamination and chose not to reselect the main tank for the remainder of the flight. After considering the aircraft’s performance, handling characteristics and engine instrument indications, the pilot assessed that the right engine, while not able to generate normal power, was still producing some power and that this would assist in reaching Archerfield. Based on the partial power loss diagnosis, the pilot decided not to shut down and secure the engine which would have included feathering the propeller. At 0556, at about 20 NM south of Archerfield at approximately 3,300 ft, the pilot advised air traffic control (ATC) that they had experienced an engine malfunction and requested to maintain altitude. With maximum power being set on the fully operating left engine, the aircraft was unable to maintain height and was descending at about 100 ft/min. Even though the aircraft was unable to maintain height, the pilot calculated that the aircraft should have been able to make it to Archerfield and did not declare an emergency at that time. At 0602, about 12 minutes after the power loss on the right engine, the left engine began to run rough and the pilot observed the left low fuel flow warning light illuminate on the annunciator panel. This was followed by severe rough running and surging from the left engine which produced a series of pronounced yawing movements. The pilot did not run through the checklist a second time for the left engine, reporting that they completed the remaining item on the checklist for the left engine by switching the left engine’s fuel supply to the auxiliary tank. The pilot once again elected not to change tank selections back to mains. With both engines malfunctioning and both propellers unfeathered, the rate of descent increased to about 1,500 ft/min. The pilot advised that following the second power loss, it was clear that the aircraft would not be able to make it to Archerfield and their attention shifted from troubleshooting and performance management to finding somewhere to conduct a forced landing. ADS-B data showed the aircraft was at about 1,600 ft when the left engine malfunctioned. The pilot stated that they aimed to stay above the minimum control speed, which for VH-HJE was 72 kt. The aircraft was manoeuvred during the brief search), during which time the ground speed fluctuated from 110 kt to a low of 75 kt. It was calculated that in the prevailing wind, this would have provided an approximate indicated airspeed of 71 kt; equal to the aircraft’s clean configuration stall speed. The pilot declared an emergency and advised ATC that they were unable to make Archerfield Airport and would be conducting an off-airport forced landing. With very limited suitable landing areas available, the pilot elected to leave the flaps and gear retracted to minimize drag to ensure they would be able to make the selected landing area. At about 0605, the aircraft touched down in a rail corridor beside the railway line, and the aircraft’s left wing struck a wire fence. The aircraft hit several trees, sustaining substantial damage to the fuselage and wings. The pilot received only minor injuries in the accident and was able to exit through the rear door of the aircraft.

• switched on both emergency fuel boost pumps

• advanced both mixture levers to RICH

• cycled the throttle to full throttle and then returned it to its previous setting without fully closing the throttle

• moved the right fuel selector from main tank to auxiliary

• disconnected the autopilot and retrimmed the aircraft. This did not alter the abnormal operation of the right engine, and the pilot conducted the engine roughness checklist from the aircraft pilot’s operating handbook noting the following:

• oil temperature, oil pressure, and cylinder head temperature indicated normally

• manifold absolute pressure (MAP) had decreased from 31 in Hg to 27 inHg

• exhaust gas temperature (EGT) indicated in the green range

• fuel flow indicated zero.

With no indication of mechanical failure, the pilot advised they could not rule out the possibility of fuel contamination and chose not to reselect the main tank for the remainder of the flight. After considering the aircraft’s performance, handling characteristics and engine instrument indications, the pilot assessed that the right engine, while not able to generate normal power, was still producing some power and that this would assist in reaching Archerfield. Based on the partial power loss diagnosis, the pilot decided not to shut down and secure the engine which would have included feathering the propeller. At 0556, at about 20 NM south of Archerfield at approximately 3,300 ft, the pilot advised air traffic control (ATC) that they had experienced an engine malfunction and requested to maintain altitude. With maximum power being set on the fully operating left engine, the aircraft was unable to maintain height and was descending at about 100 ft/min. Even though the aircraft was unable to maintain height, the pilot calculated that the aircraft should have been able to make it to Archerfield and did not declare an emergency at that time. At 0602, about 12 minutes after the power loss on the right engine, the left engine began to run rough and the pilot observed the left low fuel flow warning light illuminate on the annunciator panel. This was followed by severe rough running and surging from the left engine which produced a series of pronounced yawing movements. The pilot did not run through the checklist a second time for the left engine, reporting that they completed the remaining item on the checklist for the left engine by switching the left engine’s fuel supply to the auxiliary tank. The pilot once again elected not to change tank selections back to mains. With both engines malfunctioning and both propellers unfeathered, the rate of descent increased to about 1,500 ft/min. The pilot advised that following the second power loss, it was clear that the aircraft would not be able to make it to Archerfield and their attention shifted from troubleshooting and performance management to finding somewhere to conduct a forced landing. ADS-B data showed the aircraft was at about 1,600 ft when the left engine malfunctioned. The pilot stated that they aimed to stay above the minimum control speed, which for VH-HJE was 72 kt. The aircraft was manoeuvred during the brief search), during which time the ground speed fluctuated from 110 kt to a low of 75 kt. It was calculated that in the prevailing wind, this would have provided an approximate indicated airspeed of 71 kt; equal to the aircraft’s clean configuration stall speed. The pilot declared an emergency and advised ATC that they were unable to make Archerfield Airport and would be conducting an off-airport forced landing. With very limited suitable landing areas available, the pilot elected to leave the flaps and gear retracted to minimize drag to ensure they would be able to make the selected landing area. At about 0605, the aircraft touched down in a rail corridor beside the railway line, and the aircraft’s left wing struck a wire fence. The aircraft hit several trees, sustaining substantial damage to the fuselage and wings. The pilot received only minor injuries in the accident and was able to exit through the rear door of the aircraft.

Probable cause:

The following contributing factors were identified:

- It is likely that the pilot did not action the checklist items relating to the selection of main fuel tanks for descent. The fuel supply in the auxiliary tanks was subsequently consumed resulting in fuel starvation and loss of power from the right then left engine.

- Following the loss of power to the right engine, the pilot misinterpreted the engine instrument indications as a partial power loss and carried out the rough running checklist but did not select the main tanks that contained substantial fuel to restore engine power, or feather the propeller. This reduced the available performance resulting in the aircraft being unable to maintain altitude.

- When the left engine started to surge and run rough, the pilot did not switch to the main tank that contained substantial fuel, necessitating an off‑airport forced landing.

- It is likely that the pilot was experiencing a level of fatigue shown to have an effect on performance.

- As the pilot was maneuvering for the forced landing there was a significant reduction of airspeed. This reduced the margin over the stall speed and increased the risk of loss of control.

- Operator guidance material provided different fuel flow figures in the fuel policy and flight crew operating manual for the PA-31 aircraft type.

- The operator’s fuel monitoring practices did not detect higher fuel burns than what was specified in fuel planning data.

- The forced landing site selected minimized the risk of damage and injury to those on the ground and the controlled touchdown maximized the chances of survivability.

- It is likely that the pilot did not action the checklist items relating to the selection of main fuel tanks for descent. The fuel supply in the auxiliary tanks was subsequently consumed resulting in fuel starvation and loss of power from the right then left engine.

- Following the loss of power to the right engine, the pilot misinterpreted the engine instrument indications as a partial power loss and carried out the rough running checklist but did not select the main tanks that contained substantial fuel to restore engine power, or feather the propeller. This reduced the available performance resulting in the aircraft being unable to maintain altitude.

- When the left engine started to surge and run rough, the pilot did not switch to the main tank that contained substantial fuel, necessitating an off‑airport forced landing.

- It is likely that the pilot was experiencing a level of fatigue shown to have an effect on performance.

- As the pilot was maneuvering for the forced landing there was a significant reduction of airspeed. This reduced the margin over the stall speed and increased the risk of loss of control.

- Operator guidance material provided different fuel flow figures in the fuel policy and flight crew operating manual for the PA-31 aircraft type.

- The operator’s fuel monitoring practices did not detect higher fuel burns than what was specified in fuel planning data.

- The forced landing site selected minimized the risk of damage and injury to those on the ground and the controlled touchdown maximized the chances of survivability.

Final Report: