Country

Crash of a Cessna 414A chancellor in McKinney: 2 killed

Date & Time:

Jun 27, 2024 at 1028 LT

Registration:

N414BS

Survivors:

Yes

MSN:

414A-0504

YOM:

1980

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

2

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

2

Circumstances:

Shortly after takeoff from McKinney Airport, while in initial climb, the twin engine airplane entered an uncontrolled descent and crashed inverted in a quarry, bursting into flames. Two people were killed and a third occupant was seriously injured. It is believed that the pilot encountered engine problems shortly after departure.

Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in Patterson: 2 killed

Date & Time:

Oct 12, 2023 at 1511 LT

Registration:

N880A

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Gonzales – Patterson

MSN:

414-0397

YOM:

1973

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

1

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

2

Circumstances:

The twin engine airplane departed Gonzales-Louisiana Regional Airport at 1456LT on a short flight to Patterson. Following a left hand turn, the airplane descended to Patterson-Harry P. Williams Airport when it crashed 300 feet short of runway 06 threshold, bursting into flames. The airplane was destroyed and both occupants were killed. Patterson-Harry P. Williams Airport is located 64 km southwest of Gonzales-Louisiana Regional Airport.

Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in Modesto: 1 killed

Date & Time:

Jan 18, 2023 at 1307 LT

Registration:

N4765G

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Modesto – Concord

MSN:

414-0940

YOM:

1977

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

1

Captain / Total hours on type:

9.00

Aircraft flight hours:

3574

Circumstances:

Shortly after taking off, the pilot was instructed to change from the airport tower frequency to the departure control frequency. Numerous radio transmissions followed between tower personnel and the pilot that indicated the airplane’s radio was operating normally on the tower frequency, but the pilot could not change frequencies to departure control as directed. The pilot subsequently requested and received approval to return to the departure airport. During the flight back to the airport, the pilot made radio transmissions that indicated he continued to troubleshoot the radio problems. The airplane’s flight track showed the pilot flew directly toward the runway aimpoint about 1,000 ft from, and perpendicular to, the runway during the left base turn to final and allowed the airplane to descend as low as 200 ft pressure altitude (PA). The pilot then made a right turn about .5 miles from the runway followed by a left turn towards the runway. A pilot witness near the accident location observed the airplane maneuvering and predicted the airplane was going to stall. The airplane’s airspeed decreased to about 53 knots (kts) during the left turn and video showed the airplane’s bank angle increased before the airplane aerodynamically stalled and impacted terrain. Post accident examination of the airframe, engines, and review of recorded engine monitoring data revealed no evidence of any preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation. Toxicology testing showed the pilot had diphenhydramine, a sedating antihistamine, in his liver and muscle tissue. While therapeutic levels could not be determined, side effects such as diminished psychomotor performance from his use of diphenhydramine were not evident from operational evidence. Thus, the effects of the pilot’s use of diphenhydramine was not a factor in this accident. The accident is consistent with the pilot becoming distracted by the reported non-critical radio anomaly and turning base leg of the traffic pattern too early during his return to the airport. The pilot then failed to maintain adequate airspeed and proper bank angle while maneuvering from base leg to final approach, resulting in an aerodynamic stall and impact with terrain.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack and failure to maintain proper airspeed during a turn to final, resulting in an aerodynamic stall and subsequent impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s distraction due to a non-critical radio anomaly.

Final Report:

Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in North Palm Beach

Date & Time:

Oct 8, 2020 at 1115 LT

Registration:

N8132Q

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

North Palm Beach - Claxton

MSN:

414-0032

YOM:

1969

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

5

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

897.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

5

Aircraft flight hours:

6377

Circumstances:

The copilot, who was seated in the right seat, reported that after an uneventful run-up and taxi, the pilot, who was seated in the left seat, initiated the takeoff. The airplane remained on the runway past the point at which takeoff should have occurred and the copilot observed the pilot attempting to pull back on the control yoke but it would not move. The copilot then also attempted to pull back on the control yoke but was also unsuccessful. Observing that the end of the runway was nearing, the copilot aborted the takeoff by reducing the throttle to idle and applying maximum braking. The airplane overran the runway into rough and marshy terrain, where it came to rest partially submerged in water. Postaccident examination of the airplane and flight controls found no evidence of preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation. Specifically, examination of the elevator flight control rigging, in addition to functional checks of the elevator, confirmed continuity and normal function. Additionally, the flight control lock was found on the floor near the rudder pedals on the left side of the cockpit. Due to a head injury sustained during the accident, the pilot was unable to recall most of the events that transpired during the accident. The pilot did state that he typically removed the control lock during the preflight inspection and that he would place it in his flight bag. He thought that a shoulder injury may have led to the control lock missing the flight bag, and why it was found behind the rudder pedals after the accident. Review and analysis of a video that captured the airplane during its taxi to the runway showed that the elevator control position was similar to what it would be with the control lock installed. While the pilot and copilot reported that they did not observe the control lock installed during the takeoff, the position of the elevator observed on the video, the successful postaccident functional test of elevator, and the unsecured flight control lock being located behind the pilot’s rudder pedals after the accident suggest that the control anomaly experienced by the pilots may have been a result of the control lock remaining inadvertently installed and overlooked by both pilots prior to the takeoff. According to the airframe manufacturer’s preflight and before takeoff checklists, the flight control lock must be removed during preflight, prior to engine start and taxi, and the flight controls must be checked prior to takeoff. Regardless of why the elevator control would not move during the takeoff, a positive flight control check prior to the takeoff should have detected any such anomaly. It is likely that the pilot failed to conduct a flight control check prior to takeoff. Further, the pilot failed to abort the takeoff at the first indication that there was a problem. Although delayed, the copilot’s decision to take control of the airplane and abort the takeoff likely mitigated the potential for more severe injury to the occupants and damage to the airplane.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s inadequate preflight inspection during which he failed to detect a flight control abnormality, and his failure to expediently abort the takeoff, which resulted in the co-pilot performing a delayed aborted takeoff and the subsequent runway overrun.

Final Report:

Crash of a Cessna 414A Chancellor in Colonia: 1 killed

Date & Time:

Oct 29, 2019 at 1058 LT

Registration:

N959MJ

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Leesburg - Linden

MSN:

414A-0471

YOM:

1980

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

1

Captain / Total hours on type:

1384.00

Aircraft flight hours:

7712

Circumstances:

The pilot was conducting a GPS circling instrument approach in instrument meteorological conditions to an airport with which he was familiar. During the final minute of the flight, the airplane descended to and leveled off near the minimum descent altitude (MDA) of about 600 ft mean sea level (msl). During this time, the airplane’s groundspeed slowed from about 90 knots to a low of 65 knots. In the few seconds after reaching 65 knots groundspeed, the flight track abruptly turned left off course and the airplane rapidly descended. The final radar point was recorded at 200 ft msl less than 1/10 mile from the accident site. Two home surveillance cameras captured the final few seconds of the flight. The first showed the airplane in a shallow left bank that rapidly increased until the airplane descended in a steep left bank out of camera view below a line of trees. The second video captured the final 4 seconds of the flight; the airplane entered the camera view already in a steep left bank near treetop level, and continued to roll to the left, descending out of view. Both videos showed the airplane flying below an overcast cloud ceiling, and engine noise was audible until the sound of impact. Postaccident examination of the airplane revealed no evidence of preimpact mechanical malfunctions that would have precluded normal operation. The propeller signatures, witness impact marks, audio recordings, and witness statements were all consistent with the engines producing power at the time of impact. The pilot likely encountered restricted visibility of about 2 statute miles with mist and ceilings about 700 ft msl. When the airplane deviated from the final approach course and descended below the MDA, the destination airport remained 3.5 statute miles to the northeast. Although the airplane was observed to be flying below the overcast cloud layer, given the restricted visibility, it is likely that the pilot was unable to visually identify the airport or runway environment at any point during the approach. According to airplane flight manual supplements, the stall speed likely varied from 76 to 67 knots indicated airspeed. The exact weight and balance and configuration of the airplane could not be determined. Based upon surveillance video, witness accounts, and automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast data, it is likely that, as the pilot leveled off the airplane near the MDA, the airspeed decayed below the aerodynamic stall speed, and the airplane entered an aerodynamic stall and spin from which the pilot was unable to recover. Based on a readout of the pilot’s cardiac monitoring device and autopsy findings, while the pilot had a remote history of arrhythmia, sudden incapacitation was not a factor in this accident. Autopsy findings suggested that the pilot’s traumatic injuries were not immediately fatal; soot material in both the upper and lower airways provided evidence that the pilot inhaled smoke. This autopsy evidence supports that the pilot’s elevated carboxyhemoglobin level was from smoke inhalation during the postcrash fire. In addition, there were no distress calls received from the pilot and there was no evidence found that would indicate there was an in-flight fire. Thus, carbon monoxide exposure, as determined by the carboxyhemoglobin level, was not a contributing factor to the accident.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s failure to maintain airspeed during a circling instrument approach procedure, which resulted in an exceedance of the airplane’s critical angle of attack and an aerodynamic stall and spin.

Final Report:

Crash of a Cessna 414A Chancellor in Yorba Linda: 5 killed

Date & Time:

Feb 3, 2019 at 1345 LT

Registration:

N414RS

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Fullerton – Minden

MSN:

414A-0821

YOM:

1981

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

5

Aircraft flight hours:

9610

Circumstances:

The commercial pilot departed for a cross-country, personal flight with no flight plan filed. No evidence was found that the pilot received a preflight weather briefing; therefore, it could not be determined if he checked or received any weather information before or during the accident flight. Visual meteorological conditions existed at the departure airport; however, during the departure climb, the weather transitioned to instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) with precipitation, microburst, and rain showers over the accident area. During the takeoff clearance, the air traffic controller cautioned the pilot about deteriorating weather conditions about 4 miles east of the airport. Radar data showed that, about 5 1/2 minutes after takeoff, the airplane had climbed to about 7,800 ft above ground level before it started a rapid descending right turn and subsequently impacted the ground about 9.6 miles east of the departure airport. Recorded data from the airplane’s Appareo Stratus 2S (portable ADS-B receiver and attitude heading and reference system) revealed that, during the last 15 seconds of the flight, the airplane’s attitude changed erratically with the pitch angle fluctuating between 45° nose-down and 75°nose-up, and the bank angle fluctuating between 170° left and 150° right while descending from 5,500 to 500 ft above ground level, indicative of a loss of airplane control shortly after the airplane entered the clouds. Several witnesses located near the accident site reported seeing the airplane exit the clouds at a high descent rate, followed by airplane parts breaking off. One witness reported that he saw the airplane exit the overcast cloud layer with a nose down pitch of about 60°and remain in that attitude for about 4 to 5 seconds “before initiating a high-speed dive recovery,” at the bottom of which, the airplane began to roll right as the left horizontal stabilizer separated from the airplane, immediately followed by the remaining empennage. He added that the left wing then appeared to shear off near the left engine, followed by the wing igniting. An outdoor home security camera, located about 0.5 mile north-northwest of the accident location, captured the airplane exiting the clouds trailing black smoke and then igniting. Examination of the debris field, airplane component damage patterns, and the fracture surfaces of separated parts revealed that both wings and the one-piece horizontal stabilizer and elevators were separated from the empennage in flight due to overstress, which resulted from excessive air loads. Although the airplane was equipped with an autopilot, the erratic variations in heading and altitude during the last 15 seconds of the flight indicated that the pilot was likely hand-flying the airplane; therefore, he likely induced the excessive air loads while attempting to regain airplane control. Conditions conducive to the development of spatial orientation existed around the time of the in-flight breakup, including restricted visibility and the flight entering IMC. The flight track data was consistent with the known effects of spatial disorientation and a resultant loss of airplane control. Therefore, the pilot likely lost airplane control after inadvertently entering IMC due to spatial disorientation, which resulted in the exceedance of the airplane’s design stress limits and subsequent in-flight breakup. Contributing to accident was the pilot’s improper decision to conduct the flight under visual flight rules despite encountering IMC and continuing the flight when the conditions deteriorated. Toxicology testing on specimens from the pilot detected the presence of delta-9-tetrahydrocanninol (THC) in heart blood, which indicated that the pilot had used marijuana at some point before the flight. Although there is no direct relationship between postmortem blood levels and antemortem effects from THC, it does undergo postmortem redistribution. Therefore, the antemortem THC level was likely lower than detected postmortem level due to postmortem redistribution from use of marijuana days previously, and it is unlikely that the pilot’s use of marijuana contributed to his poor decision-making the day of the accident. The toxicology testing also detected 67 ng/mL of the sedating antihistamine diphenhydramine. Generally, diphenhydramine is expected to cause sedating effects between 25 to 1,120 ng/mL. However, diphenhydramine undergoes postmortem redistribution, and the postmortem heart blood level may increase by about three times. Therefore, the antemortem level of diphenhydramine was likely at or below the lowest level expected to cause significant effects, and thus it is unlikely that the pilot’s use of diphenhydramine contributed to the accident.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s failure to maintain airplane control after entering instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) while climbing due to spatial disorientation, which resulted in the exceedance of the airplane’s design stress limits and subsequent in-flight break-up. Contributing to accident was the pilot's improper decision to conduct the flight under visual flight rules and to continue the flight when conditions deteriorated.

Final Report:

Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in Santa Ana: 5 killed

Date & Time:

Aug 5, 2018 at 1229 LT

Registration:

N727RP

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Concord – Santa Ana

MSN:

414-0385

YOM:

1973

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

4

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

5

Captain / Total hours on type:

120.00

Aircraft flight hours:

3963

Circumstances:

The pilot and four passengers were nearing the completion of a cross-county business flight. While maneuvering in the traffic pattern at the destination airport, the controller asked the pilot if he could accept a shorter runway. The pilot said he could not, so he was instructed to enter a holding pattern for sequencing; less than a minute later, the pilot said he could accept the shorter runway. He was instructed to conduct a left 270° turn to enter the traffic pattern. The pilot initiated a left bank turn and then several seconds later the bank increased, and the airplane subsequently entered a steep nose-down descent. The airplane impacted a shopping center parking lot about 1.6 miles from the destination airport. A review of the airplane's flight data revealed that, shortly after entering the left turn, and as the airplane’s bank increased, its airspeed decreased to about 59 knots, which was well below the manufacturer’s published stall speed in any configuration. Postaccident examination of the airframe and engines revealed no anomalies that would have precluded normal operation. It is likely that the pilot failed to maintain airspeed during the turn, which resulted in an exceedance of the aircraft's critical angle of attack and an aerodynamic stall.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s failure to maintain adequate airspeed while maneuvering in the traffic pattern which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and subsequent spin at a low altitude, which the pilot was unable to recover from.

Final Report:

Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in Enstone

Date & Time:

Jun 26, 2018 at 1320 LT

Registration:

N414FZ

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Enstone – Dunkeswell

MSN:

414-0175

YOM:

1971

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

1

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

9.00

Circumstances:

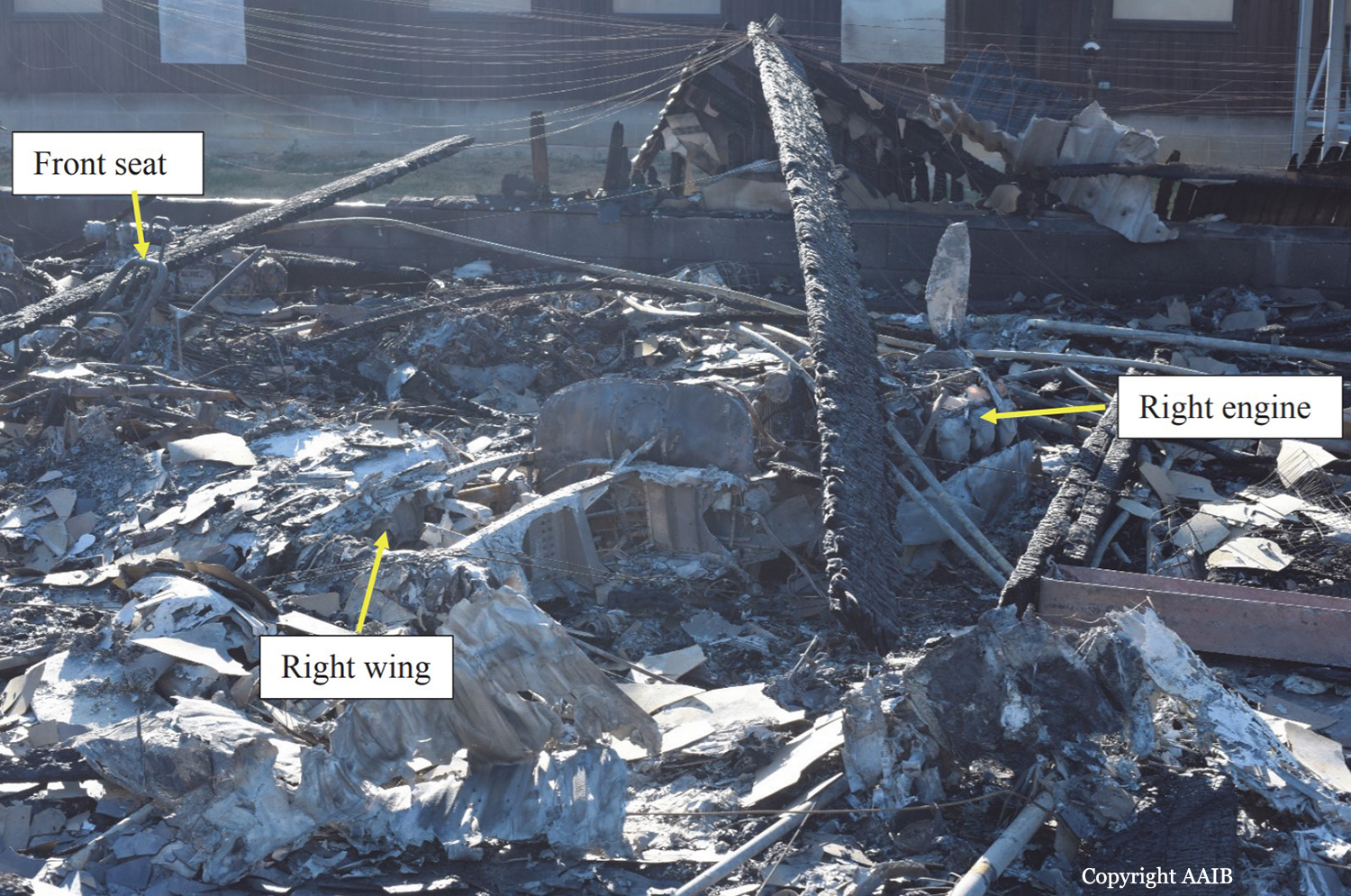

The aircraft departed Dunkeswell Airfield on the morning of the accident for a flight to Retford (Gamston) Airfield with three passengers on board, two of whom held flying licences. The passengers all reported that the flight was uneventful and after spending an hour on the ground the aircraft departed with two passengers for Enstone Airfield. This flight was also flown without incident.The pilot reported that before departing Enstone he visually checked the level in the aircraft fuel tanks and there was 390 ltr (103 US gal) on board, approximately half of which was in the wingtip fuel tanks. After spending approximately one hour on the ground the pilot was heard to carry out his power checks before taxiing to the threshold of Runway 08 for a flight back to Dunkeswell with one passenger onboard). During the takeoff run the left engine was heard to stop and the aircraft veered to the left as it came to a halt. The pilot later recalled that he had seen birds in the climbout area and this was a factor in the abandoned takeoff. The aircraft was then seen to taxi to an area outside the Oxfordshire Sport Flying Club, where the pilot attempted to start the left engine, during which time the right engine also stopped. The right engine was restarted, and several attempts appeared to have been made to start the left engine, which spluttered into life before stopping again. Eventually the left engine started, blowing out clouds of white and black smoke. After the left engine was running smoothly the pilot was seen to taxi to the threshold for Runway 08. The takeoff run sounded normal and the landing gear was seen to retract at a height of approximately 200 ft agl. The climbout was captured on a video recording taken by an individual standing next to the disused runway, approximately 400 m to the south of Runway 08. The aircraft was initially captured while it was making a climbing turn to the right and after 10 seconds the wings levelled, the aircraft descended and disappeared behind a tree line. After a further 5 seconds the aircraft came into view flying west over buildings to the east of the disused runway at a low height, in a slightly nose-high attitude. The right propeller appeared to be rotating slowly, there was some left rudder applied and the aircraft was yawed to the right. The left engine could be heard running at a high rpm and the landing gear was in the extended position. The aircraft appeared to be in a gentle right turn and was last observed flying in a north-west direction. The video then cut away from the aircraft for a further 25 seconds and when it returned there was a plume of smoke coming from buildings to the north of the runway. The pilot reported that the engine had lost power during a right climbing turn during the departure. He recovered the aircraft to level flight and selected the ‘right fuel booster’ pump (auxiliary pump) and the engine recovered power. He decided to return to Enstone and when he was abeam the threshold for Runway 08 the right engine stopped. He feathered the propeller on the right engine and noted that the single-engine performance was insufficient to climb or manoeuvre and, therefore, he selected a ploughed field to the north of Enstone for a forced landing. During the approach the pilot noticed that the left engine would only produce “approximately 57%” of maximum power, with the result that he could not make the field and crashed into some farm buildings. There was an immediate fire following the accident and the pilot and passenger both escaped from the wreckage through the rear cabin door. The pilot sustained minor burns. The passenger, who was taken to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, sustained burns to his body, a fractured vertebra, impact injuries to his chest and lacerations to his head.

Probable cause:

The pilot and the passengers reported that both engines operated satisfactory on the two flights prior to the accident flight. No problems were identified with the engines during the maintenance activity carried out 25 and 5 flying hours prior to the accident and the engine power checks carried out at the start of the flight were also satisfactory. It is therefore unlikely that there was a fault on both engines which would have caused the left engine to stop during the aborted takeoff and the right engine to stop during the initial climb. The aircraft was last refuelled at Dunkeswell Airfield and had successfully undertaken two flights prior to the accident flight. There had been no reports to indicate that the fuel at Dunkeswell had been contaminated; therefore, fuel contamination was unlikely to have been the cause. The pilot reported that there was sufficient fuel onboard the aircraft to complete the flight, which was evident by the intense fire in the poultry farm, most probably caused by the fuel from the ruptured aircraft fuel tanks. With sufficient fuel onboard for the aircraft to complete the flight, the most likely cause of the left engine stopping during the aborted takeoff, and the right engine stopping during the accident flight, was a disruption in the fuel supply between the fuel tanks and engine fuel control units. The reason for this disruption could not be established but it is noted that the fuel system in this design is more complex than in many light twin-engine aircraft. The AAIB calculated the single-engine climb performance during the accident flight using the performance curves3 for engines not equipped with the RAM modification. It was a hot day and the aircraft was operating at 280 lb below its maximum takeoff weight. Assuming the landing gear and flaps were retracted, the engine cowls on the right engine were closed and the aircraft was flown at 101 kt, then the single-engine climb performance would have been 250 ft/min. However, the circumstances of the loss of power at low altitude would have been challenging and, shortly before the accident, the aircraft was seen flying with the landing gear extended and the right engine still windmilling. These factors would have adversely affected the single-engine performance and might explain why the pilot was no longer able to maintain height.

Final Report: