Crash of a De Havilland DHC-3T Otter near Hydaburg

Date & Time:

Jul 10, 2018 at 0835 LT

Registration:

N3952B

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Klawock – Ketchikan

MSN:

225

YOM:

1957

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

10

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

306.00

Aircraft flight hours:

16918

Circumstances:

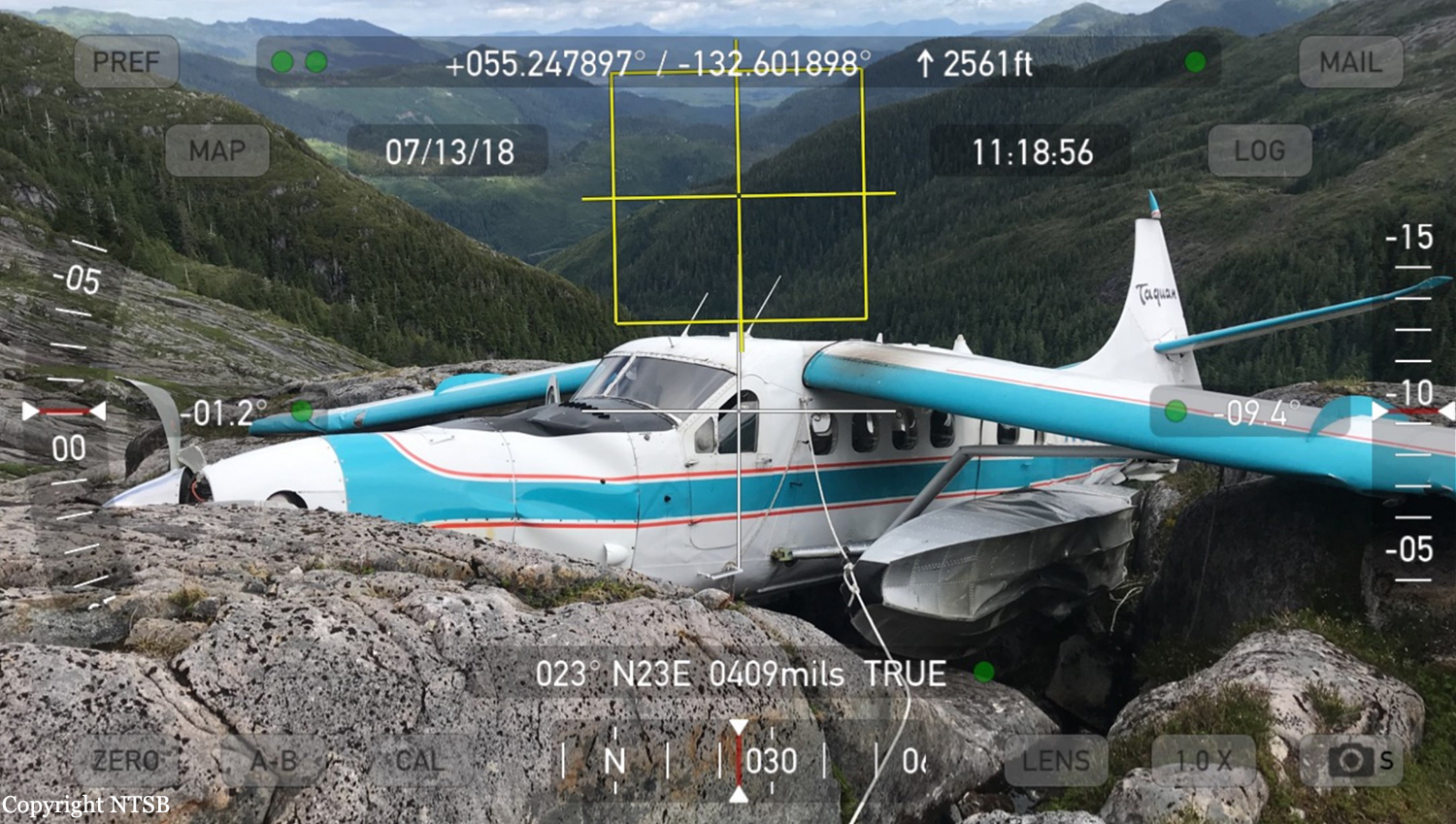

The airline transport pilot was conducting a commercial visual flight rules (VFR) flight transporting 10 passengers from a remote fishing lodge. According to the pilot, while in level cruise flight about 1,100 ft mean sea level (msl) and as the flight progressed into a mountain pass, visibility decreased rapidly. In an attempt to turn around and return to VFR conditions, the pilot initiated a climbing right turn. Before completing the 180° right turn, he saw what he believed to be a body of water and became momentarily disoriented, so he leveled the wings. Shortly thereafter, he realized that the airplane was approaching an area of snow-covered mountainous terrain, so he applied full power and initiated a steep climb; the airspeed decayed, and the airplane collided with an area of rocky, rising terrain, which resulted in substantial damage to the wings and fuselage. The pilot reported no mechanical malfunctions or anomalies that would have precluded normal operation, and the examination of the airframe and engine revealed no evidence of mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation. The weather forecast at the accident time included scattered clouds at 2,500 ft msl, overcast clouds at 5,000 ft msl with cloud tops to 14,000 ft and clouds layered above that to flight level 250, and isolated broken clouds at 2,500 ft with light rain. AIRMET advisory SIERRA for "mountains obscured in clouds/precipitation" was valid at the time of the accident. Conditions were expected to deteriorate. Passenger interviews revealed that through the course of the flight, the airplane was operating in marginal visual meteorological conditions and occasional instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) with areas of precipitation, reduced visibility, obscuration, and, at times, little to no forward visibility. Thus, based on weather reports and forecasts, and the pilot's and passengers' statements, it is likely that the flight encountered IMC as it approached mountainous terrain and that the pilot then lost situational awareness. The airplane was equipped with a terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS); however, the alerts were inhibited at the time of the accident. Although the TAWS was required to be installed per Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations, there is no requirement for it to be used. All company pilots interviewed stated that the TAWS inhibit switch remained in the inhibit position unless a controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) escape maneuver was being accomplished. However, the check airman who last administered the accident pilot's competency check stated that the TAWS inhibit switch was never moved, even during a CFIT escape maneuver. The unwritten company policy to leave the TAWS in the inhibit mode and the failure of the pilot to move the TAWS out of the inhibit mode when weather conditions began to deteriorate were inconsistent with the goal of providing the highest level of safety. However, if the pilot had been using TAWS, due to the fact that he was operating at a lower altitude and thus would have likely received numerous nuisance alerts, the investigation could not determine the extent to which TAWS would have impacted the pilot's actions. At the time of the accident, the director of operations (DO) for the company resided in another city and served as DO for another air carrier as well. He traveled to the company's main base of operation about once per month but was available via telephone. According to the chief pilot, he had assumed a large percentage of the DO's duties. The president of the company said that the chief pilot had taken over "officer of the deck" and "we're just basically using him [the DO] for his recordkeeping." The FAA was aware that the company's DO was also DO for another commuter operation. FAA Flight Standards District Office management and principal operations inspectors allowed him to continue to hold those positions, although it was contrary to the guidance provided in FAA Order 8900.1. The company's General Operations Manual (GOM) only listed the DO, the chief pilot, and the president by name as having the authority to exercise operational control. However, numerous company personnel stated that operational control could be and was routinely delegated to senior pilots. The GOM stated that the DO "routinely" delegated the duty of operational control to flight coordinators, but the flight coordinator on duty at the time of the accident stated that she did not have operational control. In addition, the investigation revealed numerous inadequate and missing operational control procedures and processes in company manuals and operations specifications. Based on the FAA's inappropriate approval of the DO, the insufficient company onsite management, the inadequate operational control procedures, and the exercise of operational control by unapproved persons likely resulted in a lack of oversight of flight operations, inattentive and distracted management personnel, and a loss of operational control within the air carrier. However, the investigation could not determine the extent to which any changes to operational control, company management, and FAA oversight would have influenced the pilot's decision to continue the VFR flight into IMC.

Probable cause:

The pilot's decision to continue the visual flight rules flight into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in controlled flight into terrain.

Final Report: