Circumstances:

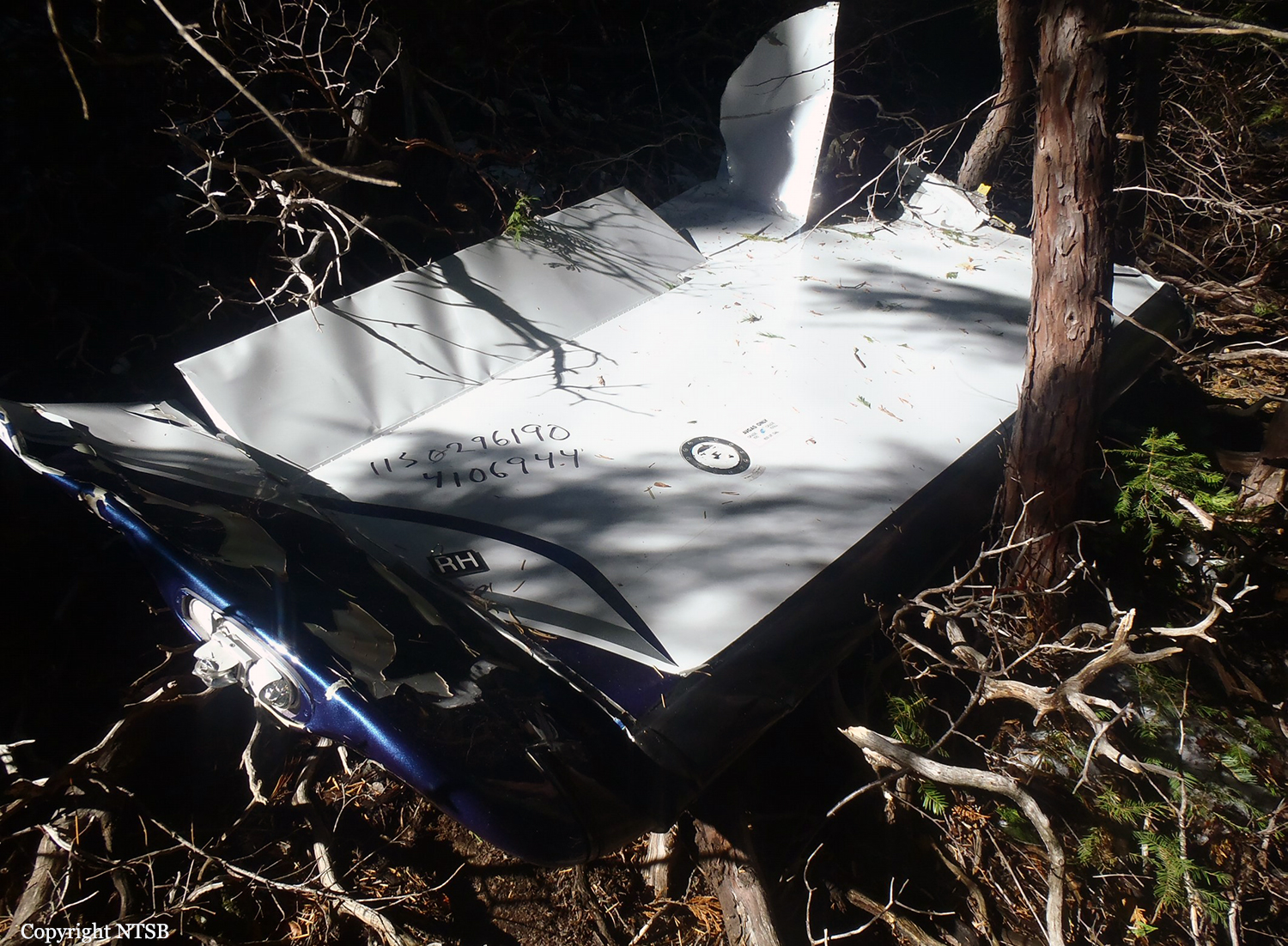

On July 6, 2013, about 1128 Pacific daylight time, a Boeing 777-200ER, Korean registration HL7742, operating as Asiana Airlines flight 214, was on approach to runway 28L when it struck a seawall at San Francisco International Airport (SFO), San Francisco, California. Three of the 291 passengers were fatally injured; 40 passengers, 8 of the 12 flight attendants, and 1 of the 4 flight crewmembers received serious injuries. The other 248 passengers, 4 flight attendants, and 3 flight crewmembers received minor injuries or were not injured. The airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a postcrash fire. Flight 214 was a regularly scheduled international passenger flight from Incheon International Airport, Seoul, Korea, operating under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 129. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed, and an instrument flight rules flight plan was filed. The flight was vectored for a visual approach to runway 28L and intercepted the final approach course about 14 nautical miles (nm) from the threshold at an altitude slightly above the desired 3° glidepath. This set the flight crew up for a straight-in visual approach; however, after the flight crew accepted an air traffic control instruction to maintain 180 knots to 5 nm from the runway, the flight crew mismanaged the airplane’s descent, which resulted in the airplane being well above the desired 3° glidepath when it reached the 5 nm point. The flight crew’s difficulty in managing the airplane’s descent continued as the approach continued. In an attempt to increase the airplane’s descent rate and capture the desired glidepath, the pilot flying (PF) selected an autopilot (A/P) mode (flight level change speed [FLCH SPD]) that instead resulted in the autoflight system initiating a climb because the airplane was below the selected altitude. The PF disconnected the A/P and moved the thrust levers to idle, which caused the autothrottle (A/T) to change to the HOLD mode, a mode in which the A/T does not control airspeed. The PF then pitched the airplane down and increased the descent rate. Neither the PF, the pilot monitoring (PM), nor the observer noted the change in A/T mode to HOLD. As the airplane reached 500 ft above airport elevation, the point at which Asiana’s procedures dictated that the approach must be stabilized, the precision approach path indicator (PAPI) would have shown the flight crew that the airplane was slightly above the desired glidepath. Also, the airspeed, which had been decreasing rapidly, had just reached the proper approach speed of 137 knots. However, the thrust levers were still at idle, and the descent rate was about 1,200 ft per minute, well above the descent rate of about 700 fpm needed to maintain the desired glidepath; these were two indications that the approach was not stabilized. Based on these two indications, the flight crew should have determined that the approach was unstabilized and initiated a go-around, but they did not do so. As the approach continued, it became increasingly unstabilized as the airplane descended below the desired glidepath; the PAPI displayed three and then four red lights, indicating the continuing descent below the glidepath. The decreasing trend in airspeed continued, and about 200 ft, the flight crew became aware of the low airspeed and low path conditions but did not initiate a go-around until the airplane was below 100 ft, at which point the airplane did not have the performance capability to accomplish a go-around. The flight crew’s insufficient monitoring of airspeed indications during the approach resulted from expectancy, increased workload, fatigue, and automation reliance. When the main landing gear and the aft fuselage struck the seawall, the tail of the airplane broke off at the aft pressure bulkhead. The airplane slid along the runway, lifted partially into the air, spun about 330°, and impacted the ground a final time. The impact forces, which exceeded certification limits, resulted in the inflation of two slide/rafts within the cabin, injuring and temporarily trapping two flight attendants. Six occupants were ejected from the airplane during the impact sequence: two of the three fatally injured passengers and four of the seriously injured flight attendants. The four flight attendants were wearing their restraints but were ejected due to the destruction of the aft galley where they were seated. The two ejected passengers (one of whom was later rolled over by two firefighting vehicles) were not wearing their seatbelts and would likely have remained in the cabin and survived if they had been wearing their seatbelts. After the airplane came to a stop, a fire initiated within the separated right engine, which came to rest adjacent to the right side of the fuselage. When one of the flight attendants became aware of the fire, he initiated an evacuation, and 98% of the passengers successfully self-evacuated. As the fire spread into the fuselage, firefighters entered the airplane and extricated five passengers (one of whom later died) who were injured and unable to evacuate. Overall, 99% of the airplane’s occupants survived.

Probable cause:

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the flight crew’s mismanagement of the airplane’s descent during the visual approach, the pilot flying’s unintended deactivation of automatic airspeed control, the flight crew’s inadequate monitoring of airspeed, and the flight crew’s delayed execution of a go-around after they became aware that the airplane was below acceptable glidepath and airspeed tolerances.

Contributing to the accident were:

(1) the complexities of the autothrottle and autopilot flight director systems that were inadequately described in Boeing’s documentation and Asiana’s pilot training, which increased the likelihood of mode error;

(2) the flight crew’s nonstandard communication and coordination regarding the use of the autothrottle and autopilot flight director systems;

(3) the pilot flying’s inadequate training on the planning and executing of visual approaches;

(4) the pilot monitoring/instructor pilot’s inadequate supervision of the pilot flying; and (5) flight crew fatigue, which likely degraded their performance.